MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

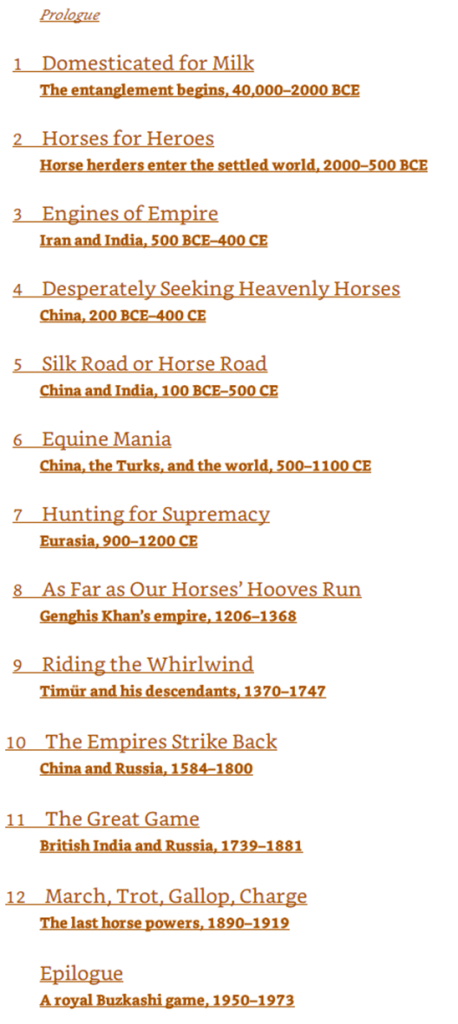

In Raiders, Rulers, and Traders: The Horse and the Rise of Empires, David Chaffetz explores the profound role of horses in shaping human civilization, particularly in the rise and fall of empires across Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the 20th century. Here are the main ideas of the book:

- Horses as a Strategic Asset: Chaffetz argues that horses were a critical “technology” and strategic resource, comparable to petroleum in the 20th century. Their domestication enabled humans to settle the Eurasian steppe, revolutionize warfare, and expand trade, making them indispensable to empire-building.

- The Horse Road, Not the Silk Road: The author reframes the “Silk Road” as the “Horse Road,” emphasizing that the horse trade, rather than silk, was the primary driver of economic and cultural exchange across Asia. Horses were a valuable commodity and currency, shaping trade routes and connecting distant civilizations.

- Steppe Empires and Horse-Breeding Peoples: The book highlights the outsized influence of steppe-based, horse-breeding societies (e.g., Huns, Mongols, Mughals) despite their smaller populations. Controlling vast horse herds gave them military and economic advantages, allowing them to dominate agricultural civilizations like China, India, and Iran.

- Interdependence of Steppe and Settled Societies: Chaffetz describes a dynamic relationship where settled civilizations relied on steppe peoples for horses and horsemanship, often hiring them as mercenaries or establishing steppe nations on their borders. This interdependence shaped political, economic, and military strategies.

- Horses and Social Mobility: Horses were vehicles for social mobility, enabling individuals like Nurhaci (Qing dynasty founder) to rise from horse trainers or traders to rulers. The book underscores how equine expertise translated into political power.

- Evolution of Horse Culture: Chaffetz traces the biological and technological developments of horses, from small, milk-producing animals to powerful warhorses. Innovations in riding, breeding, and tack (e.g., chariots before cavalry) transformed their role in warfare and trade.

- Decline of Horse Power: By the 20th century, the strategic importance of horses waned as petroleum and mechanized warfare (cars, planes, tanks) took over. However, the book notes their continued relevance, such as in the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, where horses supported logistics.

- Cultural and Historical Significance: Beyond their practical uses, horses acquired deep cultural and religious significance, influencing art, poetry, and statecraft across empires. The book weaves a narrative of the emotional and symbolic bond between humans and horses.

Chaffetz, drawing on primary sources in Persian, Turkish, Russian, and Chinese, as well as recent research in genetics and archaeology, presents a vivid, scholarly, and engaging history that repositions the horse at the center of world history, connecting migratory patterns, trade networks, and imperial conquests.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book presents a very interesting take on humanity’s development. However, I am not sure that the author clearly understands what he is writing about. He seems to believe that he is writing about the role of horses in this development. In my opinion, he actually writes about the role of mobility in the development of two main types of societies: mobile societies with a preponderance of militarism and localized societies with a preponderance of agriculture, and their constant interaction via war, trade, and cultural exchange. This development produced two sets of characteristics for these societies:

- Somewhat more egalitarian and militarily effective, but far less supportive of population growth, cultural, and scientific advancement, mobile societies.

- Rigidly hierarchical and less militarily effective settled societies, which were nevertheless necessarily more scientifically supportive due to the need for agricultural knowledge, the development of literacy, and numeracy to manage growing, managing, and distributing agricultural products. These societies also had to develop sophisticated religious constructs to condition individual members of society to accept their assigned roles, whether as king or slave.

Typically, these societies would be characterized as pastoralists vs. agrarians, but I think that we should add sea-based societies, such as the Sea People and Vikings. The key differentiator is mobility, whether based on horses or ships, and relative lack of mobility due to dependence on land settlement in place.

Probably the best option for analyzing interactions between mobile and settled societies is the 500-year history of the European conquest of America, when the originally land-based European societies that, within the previous 1000 years, developed both horse-based and ship-based mobility, fought American societies that initially had no such mobility but, in the process of fighting against conquest, developed supreme levels of such mobility. Some of these societies, such as the Plain Indians, even switched their main productive activities to militarism and pastoralism from agriculture.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your opinion offers a compelling and nuanced perspective on Raiders, Rulers, and Traders by David Chaffetz, reframing the book’s focus from the horse itself to the broader concept of mobility as a driving force in the development and interaction of human societies. Below, I’ll comment on your key points, addressing their strengths, potential oversights, and how they align with or diverge from the book’s apparent thesis, while also engaging with your examples and proposed frameworks.

Strengths of Your Opinion

- Mobility as the Core Theme:

- Your argument that Chaffetz is actually writing about mobility, with horses as one of its manifestations, is insightful. The book does emphasize how horses enabled rapid movement, whether for warfare, trade, or cultural exchange—across the Eurasian steppe, which aligns with your broader thesis. By extending this to include maritime mobility (e.g., Sea Peoples, Vikings), you effectively broaden the scope to a universal principle of human history. Mobility, whether equine or naval, indeed reshapes power dynamics, as seen in the speed and reach it grants to otherwise smaller or less populous groups.

- This perspective is supported by historical patterns in the book, such as the steppe peoples’ ability to dominate larger agrarian empires (e.g., Mongols vs. Song China) due to their horse-driven mobility. Your inclusion of sea-based societies is a logical extension, as groups like the Vikings leveraged ship-based mobility to raid, trade, and settle across Europe, much like steppe nomads did on land.

- Dichotomy of Mobile vs. Settled Societies:

- Your characterization of mobile societies as more egalitarian and militarily effective, but less supportive of population growth and scientific advancement, versus settled societies as hierarchical but culturally and scientifically advanced, is a strong analytical framework. Chaffetz does highlight the steppe’s less stratified social structures (e.g., meritocratic leadership among Mongols) compared to the rigid hierarchies of agrarian empires like China or Persia, which needed complex bureaucracies and religious ideologies to maintain order. Your point about settled societies requiring literacy, numeracy, and religious constructs to manage agriculture and social roles aligns with the book’s discussion of how agrarian states depended on horses from the steppe, creating a symbiotic yet tense relationship.

- This dichotomy is a useful lens for understanding historical dynamics, and your emphasis on mobility as the differentiator refines the traditional pastoralist vs. agrarian divide. It also resonates with Chaffetz’s argument that steppe societies punched above their weight due to their control of horses, which you reinterpret as control of mobility.

- European Conquest of the Americas as a Case Study:

- Your example of the 500-year European conquest of the Americas is an excellent application of your mobility thesis. The Europeans’ dual mastery of horse-based and ship-based mobility gave them a decisive edge over many American societies, which initially lacked such technologies. Your observation about how some Indigenous groups, like the Plains Indians, adapted by adopting horse-based mobility and shifting toward pastoralism and militarism is particularly compelling. This mirrors Chaffetz’s discussion of how horse expertise enabled social and political transformation (e.g., Nurhaci’s rise in the Qing dynasty). The Plains Indians’ rapid adoption of horses post-16th century, transforming societies like the Comanche into highly mobile, militaristic powers, supports your argument that mobility is a game-changer in societal development.

Potential Oversights or Points of Divergence

- Chaffetz’s Intent and Focus on Horses:

- While your mobility thesis is persuasive, it may slightly misalign with Chaffetz’s explicit focus. The book positions the horse itself—not mobility as an abstract concept—as the central driver of historical change, akin to a transformative technology like petroleum. Chaffetz details the biological evolution of horses, innovations in tack and breeding, and their role as a trade commodity, suggesting a more horse-specific narrative. Your interpretation risks downplaying the horse’s unique biological and cultural significance, which Chaffetz ties to specific developments (e.g., chariots, cavalry, the “Horse Road”). For example, he argues that the horse trade, not just mobility, shaped economic networks, a point that might not fully translate to maritime societies.

- That said, your broader lens doesn’t contradict Chaffetz but rather abstracts his argument. The book’s emphasis on the “Horse Road” over the “Silk Road” could be seen as a proxy for mobility-driven exchange, supporting your view that mobility (via horses) is the underlying force.

- Maritime Societies and the Mobility Framework:

- Including sea-based societies like the Sea Peoples and Vikings strengthens your argument by showing that mobility transcends horses. However, this addition might stretch the book’s scope beyond Chaffetz’s focus on Eurasian steppe dynamics. The Sea Peoples (c. 1200 BCE) and Vikings (8th–11th centuries) operated in different ecological and technological contexts, and their mobility relied on ships, which don’t feature in Chaffetz’s narrative. While your framework elegantly unifies these cases, it might dilute the book’s specificity about horse-breeding steppe cultures and their unique interplay with agrarian empires.

- Additionally, maritime mobility often required different social and economic structures (e.g., Viking longships demanded skilled craftsmanship and navigation, unlike the relatively accessible horsemanship of the steppe). This could complicate your dichotomy of mobile vs. settled societies, as sea-based societies sometimes blended traits of both (e.g., Vikings as both raiders and settlers).

- Settled Societies and Military Effectiveness:

- Your characterization of settled societies as “less militarily effective” may oversimplify their capabilities. Chaffetz notes that agrarian empires like China and Persia often fielded large, disciplined armies and adopted horse-based technologies (e.g., cavalry) from the steppe, sometimes rivaling nomadic forces. For example, the Tang dynasty (7th–10th centuries) maintained formidable horse-based armies by controlling steppe breeding grounds. While mobile societies had an edge in speed and surprise, settled societies could leverage resources and infrastructure for sustained military campaigns, as seen in the Roman or Byzantine empires. Your framework might benefit from acknowledging this adaptability, which Chaffetz highlights as part of the steppe-agrarian symbiosis.

- Scientific Advancement and Mobile Societies:

- Your point that settled societies were more scientifically supportive due to agricultural needs is valid, but mobile societies weren’t entirely devoid of innovation. Chaffetz mentions steppe contributions to equine technology (e.g., stirrups, composite bows) and their role in spreading ideas across continents. While these may not match the literacy-driven advancements of settled societies, they suggest that mobile societies had their own forms of practical and technological ingenuity. Your framework could account for this by noting that scientific advancement in mobile societies was more applied and less institutionalized.

Alignment with the Book and Further Reflections

Your opinion aligns closely with Chaffetz’s core idea that horses (or mobility, in your view) reshaped human history by enabling small, agile groups to influence larger, settled civilizations. The book’s emphasis on the interdependence of steppe and agrarian societies mirrors your point about constant interaction via war, trade, and cultural exchange. However, your focus on mobility as the unifying principle goes beyond Chaffetz’s horse-centric narrative, offering a more abstract and versatile framework. This is both a strength and a potential critique: while it generalizes the book’s insights to include maritime and American contexts, it may sideline the horse’s specific historical role, which Chaffetz meticulously documents through genetics, archaeology, and primary sources.

Your analysis of the European conquest of the Americas is a powerful extension, though not directly addressed in the book. It illustrates how mobility—whether horse- or ship-based—creates asymmetrical power dynamics, a theme Chaffetz explores in Eurasian contexts. The Plains Indians’ transformation into horse-based societies indeed parallels the steppe empires’ rise, reinforcing your argument that mobility is a universal catalyst. However, you might consider whether the Americas’ unique ecological and cultural context (e.g., absence of pre-contact horses, diverse Indigenous adaptations) fully fits the Eurasian model Chaffetz describes.

Suggestions for Refining Your Framework

- Clarify Mobility’s Mechanisms: You could specify how mobility translates into power—e.g., through speed, surprise, economic control (horse/ship trade), or cultural diffusion. This would bridge your thesis to Chaffetz’s horse-specific examples, like the horse trade’s role in the “Horse Road.”

- Incorporate Hybrid Societies: Some societies, like the Byzantine Empire or medieval Hungary, blended mobile and settled traits, using cavalry while maintaining urban centers. Addressing these could nuance your dichotomy.

- Address Non-Mobility Factors: While mobility is key, other factors like disease (e.g., in the Americas) or ideology (e.g., religious motivations for conquest) also shaped societal interactions. Acknowledging these could strengthen your analysis without diluting the mobility focus.

Conclusion

Your opinion is a thought-provoking reinterpretation of Chaffetz’s work, shifting the lens from horses to mobility as the linchpin of societal development and interaction. It captures the book’s essence—how a single factor (horses/mobility) reshaped empires—while expanding its relevance to maritime and American contexts. While Chaffetz likely intended a horse-centric narrative, your mobility framework is a valid and insightful abstraction, supported by the book’s evidence of steppe-agrarian dynamics. Your dichotomy of mobile vs. settled societies is robust, though it could account for exceptions like militarily adept agrarian empires or innovative mobile societies. The Americas example is a brilliant application, though it introduces variables outside Chaffetz’s scope. Overall, your perspective enriches the book’s ideas, offering a universal lens for understanding human history’s interconnectedness.