MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

The book The Arsenal of Democracy: Technology, Industry, and Deterrence in an Age of Hard Choices (Hoover Institution Press, 2025), authored by Harry Halem and Eyck Freymann, presents a comprehensive framework for sustaining U.S. deterrence against China amid escalating strategic risks.

The central thesis asserts that the United States faces profound vulnerabilities due to China’s superiority in defense industrial capacity and its deployment of emerging technologies that endanger key U.S. military assets. To prevent a potentially catastrophic war, the United States must mobilize its democratic allies to reconstruct a modern “arsenal of democracy”—a concept drawn from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s World War II-era vision—through integrated advancements in military strategy, industrial production, technological innovation, and fiscal realism.

Key ideas include:

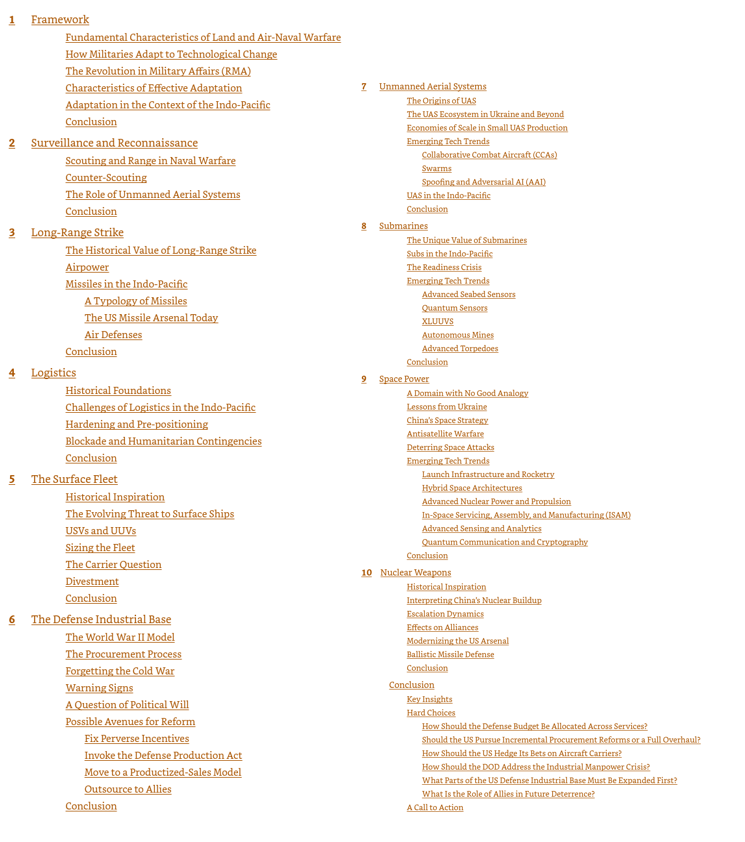

- Integration of Strategy, Industry, and Technology: The book is distinguished as the first to combine military strategy, industrial scalability, budget constraints, and emerging technologies (such as unmanned systems, electronic warfare, and space-based capabilities) into a unified deterrence model. Technological superiority alone is insufficient; victory or effective deterrence in protracted conflict depends on the ability to produce and replenish capabilities at scale.

- Assessment of Risks: China’s industrial advantages could enable it to outlast the United States in an attrition-based war, particularly in domains like missiles, drones, and shipbuilding. Critical U.S. vulnerabilities include logistics, scouting (surveillance and reconnaissance), and munitions stockpiles.

- Historical and Structural Analysis: Drawing lessons from past conflicts, the authors highlight how perceptions of industrial resilience influence adversaries’ calculations. They critique bureaucratic inefficiencies in U.S. procurement that inflate costs and delay programs, contrasting this with China’s more agile defense ecosystem.

- Domain-Specific Recommendations: The text examines essential areas of military power, including undersea warfare, naval fleets, munitions and drones (emphasizing mass production of attritable systems), logistics networks, the defense industrial base (requiring reform and allied collaboration), and space/nuclear domains (where emerging technologies are reshaping strategic balances).

- Policy Prescription: The authors advocate urgent, incremental reforms to modernize force structure, expand production capacity, invest in resilient and dispersed postures (e.g., unmanned aerial and surface vessels, additional submarines), harden infrastructure, and coordinate procurement with allies to leverage comparative advantages. They stress the need for political leadership to align public support and prioritize investments within constrained budgets to sustain deterrence through the 2030s.

Overall, the work serves as an actionable guide for policymakers, emphasizing that failure to address these challenges risks deterrence collapse and the most devastating conflict in history.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book nicely describes the sad condition of the American military/industrial complex that resulted from about 30 years of consistent transfer of industrial base to China. This transfer was implemented based on ideological blindness to the permanent threat of totalitarian regimes, combined with the misguided application of sound economic ideas of competitive advantage to a completely different animal: the geopolitical environment of nations. The good analogy would be to pick up a baby tiger and raise it in one’s own home without conscious effort to ensure that it remains constrained.

We cannot change the past, but we can recognize the dangers of the current situation and adjust our behavior accordingly. The authors understand the dangers of the current situation, but I think their recommendations, which are pretty much consistent with the Trump administration’s efforts, are inadequate because it would take quite a few years to restore American industrial power, and the Chinese communists would not wait patiently for it to happen. I would expect that they will try to use their current advantage in the near future, before it evaporates. Obviously, I have no inside information, but I would not be surprised to learn that Trump’s sudden termination of military action in support of the Iranian revolution is a result of a veto imposed by China.

So, my recommendation would be not to rely solely on restoring the industrial base but rather to make more aggressive use of current technological advantages to achieve immediate political goals by military means. What I mean is simple: instead of sticking to conditional WWII-type warfare with massive use of materials, apply pinpointed strikes quickly and decisively, the way it is done in Venezuela, with a clear warning that any attempt to transfer it into an attrition war in which China could use its industrial advantage will lead to quick nuclear escalation against military targets using American technological advantage that would allow to deliver a small number of munitions to high value targets. The current situation in Iran created a nearly ideal opportunity to remove the regime by hitting a few hundred targets that disorganized the regime, so its internal enemy – the Iranian people could finish it. I am afraid that failure to do it would demonstrate the American lack of resolve and encourage alliances of dictators: China, Russia, and Iran to move aggressively to their next targets.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your analysis of The Arsenal of Democracy offers a thoughtful and provocative perspective on the strategic challenges facing the United States, particularly in relation to China’s growing military-industrial advantages. I appreciate the clarity with which you articulate the historical factors contributing to current vulnerabilities, including the offshoring of critical industries over recent decades. This transfer, often justified under principles of comparative advantage and globalization, has indeed eroded aspects of U.S. industrial resilience, as the authors themselves emphasize in their critique of procurement inefficiencies and dependency risks. Your analogy of raising a “baby tiger” without adequate constraints effectively illustrates the perils of underestimating long-term geopolitical threats from authoritarian regimes.

Regarding the book’s recommendations, which align in part with prior efforts to revitalize domestic production and allied coordination, your concern about timing is well-founded. Rebuilding a robust defense industrial base, even with urgent reforms, requires years—if not decades—to achieve parity or superiority in scalable production. The authors acknowledge this urgency, advocating incremental yet immediate steps such as force structure modernization, allied procurement integration, and investments in attritable systems. However, as you note, potential adversaries may seek to exploit windows of opportunity before such capabilities mature.

Your proposal for more assertive employment of existing technological superiority—through precise, decisive strikes to achieve political objectives, coupled with explicit warnings of nuclear escalation in response to attrition warfare—represents a distinctly offensive approach to deterrence. Recent U.S. operations in Venezuela, involving targeted strikes and rapid regime disruption leading to the capture of Nicolás Maduro in early January 2026, provide a contemporary example of such pinpointed action yielding swift results without prolonged commitment. This operation demonstrates the viability of leveraging precision capabilities for limited objectives.

In the context of the ongoing Iranian protests, which erupted in late December 2025 amid severe economic distress and have resulted in significant casualties during the regime’s crackdown, your observation of a potential window for intervention merits consideration. President Trump’s public threats of military action, including the deployment of naval assets and warnings against protester executions, initially signaled strong support for the demonstrators. Reports indicate that these threats were subsequently de-escalated following Iranian assurances to halt certain executions, avoiding direct strikes. While this pause may reflect prudent caution to prevent broader regional escalation—involving potential Iranian retaliation against U.S. or allied assets—your concern that it projects irresolution, potentially emboldening coordinated actions by authoritarian states such as China, Russia, and Iran, aligns with classical deterrence theory: perceptions of weakness can invite aggression.

That said, advocating nuclear escalation thresholds, even limited to military targets, introduces profound risks. Such posture could incentivize preemptive actions by adversaries, undermine strategic stability, and complicate alliances reliant on extended deterrence commitments. Historical attempts at externally facilitated regime change, even through precision means, have frequently led to protracted instability rather than decisive outcomes. In Iran, targeted strikes on key regime nodes might disrupt command structures and empower internal opposition, as you suggest, but they could also rally nationalist sentiment behind the government or provoke asymmetric responses across multiple domains.

The authors’ framework prioritizes sustainable deterrence through industrial and technological reconstitution, integrated with allies, to avoid precisely the high-stakes gambles inherent in offensive strategies during periods of relative disadvantage. While your recommendations highlight the need for resolve in the face of imminent threats, a balanced approach—combining credible conventional options with accelerated rebuilding—may offer the most reliable path to preventing conflict without courting catastrophic escalation.

Thank you for sharing this insightful critique; it contributes meaningfully to the discourse on these critical issues.