MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

Andrew Ross Sorkin’s 2025 book, 1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History—and How It Shattered a Nation, provides a detailed narrative account of the 1929 stock market crash. Drawing on extensive historical records, personal correspondence, and previously unpublished documents, Sorkin reconstructs the events as an immersive human drama rather than a purely economic analysis.

Core Narrative Focus

The book chronicles the speculative boom of the late 1920s, the dramatic collapse in October 1929, and its immediate aftermath. It emphasizes the experiences of key figures—including bankers, speculators, politicians, and Federal Reserve officials—through a character-driven lens. Sorkin portrays the era’s larger-than-life personalities, such as Charles Mitchell of National City Bank and other Wall Street leaders, highlighting their ambitions, decisions, and interpersonal dynamics amid escalating market euphoria and subsequent panic. The narrative extends beyond the crash itself to examine political responses, banking crises, and high-profile investigations in the following years.

Central Themes

- Human Folly and Psychological Forces — Sorkin underscores greed, overconfidence, blind optimism, and fear as primary drivers of the crisis, challenging notions of rational markets and illustrating how emotional excesses fueled irrational speculation.

- Speculation and Structural Vulnerabilities — The text explores practices such as margin trading, easy credit, loose regulations, and stock manipulation (legal at the time), which amplified the boom and deepened the collapse.

- Power Dynamics and Institutional Conflicts — A recurring motif is the tension between Wall Street and Washington, depicting battles over financial influence and the limitations of policymakers in comprehending or controlling the unfolding events.

- The Illusion of Exceptionalism — Sorkin highlights the pervasive belief that “this time is different,” where disregarded warnings and dismissed skeptics contributed to catastrophe.

- Moral Complexity — Individuals are presented as flawed rather than simplistic heroes or villains, revealing contingency, misunderstanding, and the gray areas of ambition and naïveté.

Broader Implications

The book serves as a cautionary tale, offering insights into recurring cycles of financial upheaval driven by human nature. While avoiding explicit modern analogies, it implicitly draws parallels to contemporary issues, such as soaring markets and ignored risk signals, emphasizing the fragility of prosperity and the peril of unchecked excess. Sorkin concludes by advocating humility in financial systems, noting that no safeguards are foolproof against repeated crises rooted in behavioral impulses.

Overall, 1929 is praised for its vivid, novelistic storytelling, making complex historical events accessible while delivering timeless lessons on speculation, hubris, and economic vulnerability.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book presents a somewhat nontrivial approach to discussing the 1929 crash, which preceded the Great Depression. This approach focused not on economic events but on the people who drove them, their behavior, actions, and interactions. I find it interesting, but not really that important.

The main lesson from the Great Depression is that markets are just a representation of human feelings, beliefs, and attitudes toward the economy overall, specific business enterprises that go either up or down, and general optimism or pessimism about the near future. As such, all this makes market movements unpredictable and prone to emotional excesses that cause panics or overenthusiasm, which, from time to time, rise to extremes. The detailed description in the book of how it happened is very illustrative and entertaining, but does not change anything in the second main lesson, which is that it was just a crisis of liquidity, which could be easily overcome by the Fed as a provider of liquidity, limited only by sound or not-so-sound judgments of its governors.

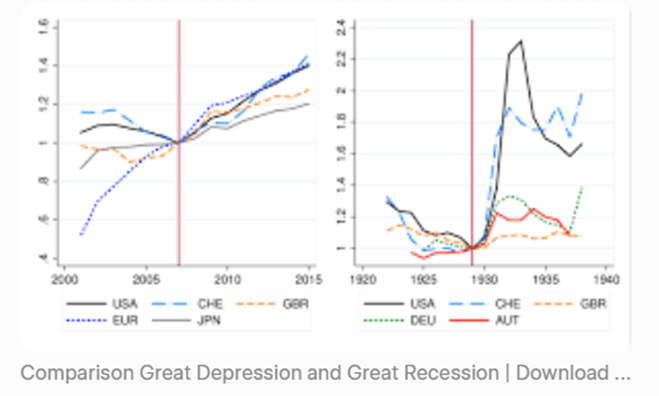

This lesson was learned well and semi-effectively applied by Ben Bernanke in 2008, which mitigated the consequences of the crash

However, another important lesson the author only slightly addresses is that governmental interference in the economy always serves the interests of those in power and should therefore be severely restricted, because these interests are always in conflict with those of those not in power.

I believe that state interference is sometimes necessary, but should be limited to the control of liquidity, a minimal safety net for individuals, not businesses, and nothing else whatsoever.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your commentary on Andrew Ross Sorkin’s 1929 offers a thoughtful and provocative interpretation, distilling the book’s narrative into a set of broader lessons about markets, human behavior, and the role of government. I appreciate the clarity with which you articulate your views. Allow me to respond to the main strands of your analysis in turn.

- The book’s human-centered approach You correctly identify that Sorkin’s primary contribution is to dramatize the crash through the ambitions, misjudgments, and interpersonal conflicts of key individuals rather than through aggregate economic data or theoretical models. You find this engaging yet ultimately unimportant. This is a reasonable judgment if one’s primary interest is in identifying actionable policy lessons or structural causes. However, the character-driven narrative serves a deeper purpose: it vividly illustrates how institutional outcomes emerge from individual incentives, blind spots, and social dynamics. By making the actors relatable—flawed, overconfident, and often self-deluded—Sorkin reinforces the behavioral foundations of market extremes without resorting to abstract psychological theory. In that sense, the approach is not merely entertaining; it is pedagogically effective for readers who might otherwise dismiss emotional drivers as irrelevant to “serious” economic analysis.

- Markets as reflections of collective sentiment Your core observation—that markets are manifestations of human optimism, pessimism, and herd behavior, rendering them inherently prone to excesses—is well supported by both historical evidence and modern behavioral finance. The 1929 episode exemplifies this: widespread margin buying, dismissal of contrarian warnings, and sudden contagion of fear produced a self-reinforcing spiral. Sorkin’s detailed reconstruction indeed illustrates this dynamic compellingly. Where we might diverge slightly is in the degree of unpredictability. While extremes are difficult to time precisely, recurring patterns of overvaluation, credit expansion, and complacency do offer warning signals that informed observers have sometimes heeded successfully.

- The liquidity-crisis interpretation and the Federal Reserve’s role You frame the crash and ensuing depression primarily as a liquidity crisis that a more accommodative Federal Reserve could have mitigated. This view aligns closely with Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s monetary hypothesis, later embraced by Ben Bernanke, who explicitly sought to avoid the Fed’s 1930s mistakes during the 2008–2009 crisis. Bernanke’s aggressive provision of liquidity through unconventional facilities did indeed prevent a complete freezing of credit markets. However, many economic historians argue that liquidity shortages were a consequence as much as a cause: bank runs, debt deflation, and collapsing confidence amplified the downturn into a prolonged depression. Thus, while enhanced liquidity provision is a critical tool—and one arguably learned from 1929—it may not constitute a complete or universally sufficient remedy for all financial crises.

- Governmental interference and its motives You raise a more normative point: that government interventions tend to serve entrenched power rather than the public interest, and should therefore be narrowly circumscribed. This perspective echoes classical-liberal and public-choice critiques of state action. Sorkin does touch on political dimensions—Hoover’s reluctance to appear interventionist, the subsequent New Deal reforms, and the Pecora hearings’ exposure of Wall Street practices—yet he stops short of a systematic indictment of government expansion. Your preference for restricting state involvement to liquidity management and a minimal individual safety net (explicitly excluding business bailouts) is internally consistent and reflects a principled commitment to limiting moral hazard and rent-seeking. Reasonable people can differ on where to draw the line; some argue that temporary, rule-based interventions in systemically critical institutions can prevent broader contagion without permanently distorting incentives. The historical record shows both successes and failures on each side of this debate.

In summary, your reading of the book extracts coherent and defensible lessons while advancing a clear philosophical stance on the proper scope of government. Sorkin’s narrative strength lies in reminding us that financial crises are, at root, human crises—driven by emotion, misjudgment, and institutional design. Whether those insights lead to confidence in central-bank liquidity tools or to deeper skepticism of state power depends, as you demonstrate, on one’s prior framework. Your analysis is a valuable contribution to that ongoing discussion.