MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

In Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies (2017), physicist Geoffrey West applies principles from physics and complexity science to reveal universal scaling laws—mathematical relationships that govern how characteristics of complex systems change with size. These laws, often expressed as power-law relationships (Y ≈ N^β, where N is size and β is the scaling exponent), emerge from optimized, hierarchical networks that distribute resources efficiently across biological and social systems.

Scaling in Biological Systems

West builds on Kleiber’s law, which states that an animal’s metabolic rate scales sublinearly with body mass to the approximately 3/4 power (β ≈ 0.75). Doubling an animal’s mass requires only about 75% more energy, not 100%, yielding economies of scale. This sublinear pattern extends to other traits: larger animals exhibit slower heart rates, longer lifespans, and a decelerated pace of life, while growth follows a sigmoid curve—rapid initial expansion followed by a plateau and eventual death.

These laws derive from fractal-like branching networks (e.g., blood vessels) that are space-filling, minimize energy expenditure, and maintain invariant terminal units (e.g., capillaries). Such optimization constrains unbounded growth in biology.

Scaling in Urban Systems

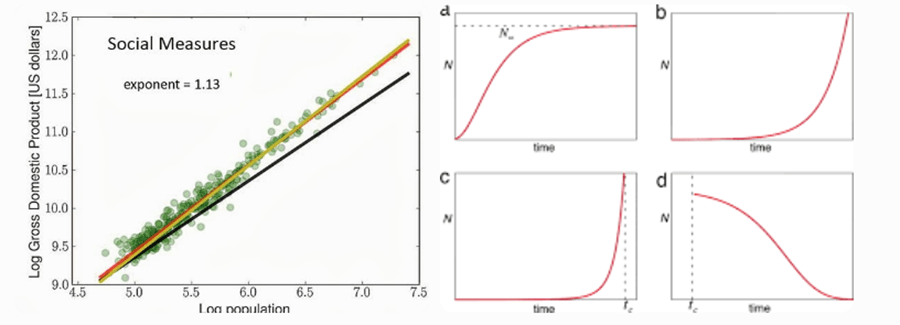

Cities display distinct scaling behaviors. Infrastructure (e.g., roads, utilities) scales sublinearly (β ≈ 0.85), requiring only about 85% more resources per population doubling, which creates efficiencies. In contrast, socioeconomic metrics (e.g., innovation, wealth creation, patents, but also crime and disease) scale superlinearly (β ≈ 1.15), producing more than proportional increases—approximately 15% extra per doubling. This superlinear scaling arises from amplified social interactions in dense networks, accelerating the pace of life (e.g., faster walking speeds in larger cities) and driving open-ended exponential growth. Unlike organisms, cities do not follow a natural sigmoid trajectory and persist through innovation cycles.

Scaling in Companies

Companies resemble biological organisms more than cities, exhibiting sublinear scaling (β ≈ 0.9–1.0) and bounded, sigmoid-like growth curves. Larger firms achieve efficiencies but face diminishing returns and limited lifespans; most companies eventually stagnate or fail, with mortality rates largely independent of age or size. Unlike cities, companies lack the sustained superlinear innovation that supports indefinite expansion.

Implications for Sustainability and Growth

West argues that superlinear urban scaling, while fueling progress, demands exponentially increasing resources and innovation to avert collapse—a “finite-time singularity” where growth outpaces adaptability. Sustaining open-ended expansion requires repeated paradigm shifts (e.g., from steam power to digital technology), but accelerating cycles raise questions about long-term viability amid resource constraints and environmental challenges.

Overall, the book presents a unified framework suggesting that network-driven scaling laws impose both constraints and opportunities, offering insights for designing resilient cities, organizations, and global systems.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book presents an unusual point of view that links the scale, growth, and complexity of different systems. The comparison among biological, societal, and business systems is particularly interesting, especially the author’s use of β and the distinction between sublinear and superlinear scaling across these systems, and his attempt to link them into a unified theory of sustainability.

I mainly agree with the author about his statement:” One of the major challenges of the twenty-first century that will have to be faced is the fundamental question as to whether human-engineered social systems, from economies to cities, which have only existed for the past five thousand years or so, can continue to coexist with the “natural” biological world from which they emerged and which has been around for several billion years. To sustain more than 10 billion people living in harmony with the biosphere at a standard of living and quality of life comparable to what we now have requires that we develop a deep understanding of the principles and underlying system dynamics of this social-environmental coupling. I have argued that a critical component of this is to develop a deeper understanding of cities and urbanization. Continuing to pursue limited and single-system approaches to the many problems we face without developing a unifying framework risks the possibility that we will squander huge financial and social capital and fail miserably in addressing the really big question, resulting in dire consequences.”

However, I think that the number of people is not a significant issue, because the current population is as large as it will be. We are already approaching a stable population level, and we will likely see a decrease when the same process that limited growth in developed countries does the same in developing countries. Similarly, cities and overall urbanization will likely be irrelevant in the future, because direct mind-to-mind communication, based on technologies such as Neuralink that provide complete sensory proximity between people, will render the body’s location largely irrelevant and enable unlimited human interaction.

Similarly, the current direction of technological development will pretty soon provide for a switch from struggle and more or less coexistence of humanity with the environment into new conditions when the environment is controlled mainly by humans, not on the local level as it is now, but on the global level, creating new closed-loop environmental systems similar to naturally occurring ones.

The biggest problem that I can imagine is not technological or scientific, but humanitarian and societal. We humans developed in an environment of conflict between US and THEM, and overcoming this will take time and substantial effort, which could be painful and protracted.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your commentary on Geoffrey West’s Scale offers a thoughtful and provocative extension of the book’s core ideas, particularly in linking scaling laws across biological, urban, and economic systems to broader questions of sustainability. The emphasis on the scaling exponent β as a unifying metric, distinguishing sublinear efficiencies from superlinear accelerations, indeed provides a compelling framework for understanding systemic constraints and opportunities.

The quoted passage from West highlights a critical interdisciplinary challenge: integrating human-engineered systems with the biosphere to support a growing population at current living standards. Your agreement with this underscores the need for a holistic, principles-based approach rather than fragmented solutions.

Regarding population dynamics, while fertility rates have declined markedly in many developed and increasingly in developing regions—reflecting the demographic transition you reference—current United Nations projections as of 2025 indicate continued global growth. The world population, approximately 8.2 billion in 2025, is expected to peak at around 10.3 billion in the mid-2080s before a modest decline to 10.2 billion by 2100. Recent revisions have lowered some estimates due to faster-than-anticipated fertility drops, but a peak significantly above current levels remains the consensus, posing sustained pressures on resources and urban systems.

On the future irrelevance of urbanization driven by technologies such as Neuralink, advancements in brain-computer interfaces are indeed remarkable. As of late 2025, Neuralink’s clinical trials have enabled individuals with paralysis to control computers, play games, and achieve basic communication through thought alone, with ongoing progress in decoding speech and intent. However, achieving full mind-to-mind sensory proximity—encompassing complete experiential sharing and rendering physical location obsolete—remains in the realm of long-term speculation. Current implementations focus on restorative functions, and widespread adoption capable of transforming social and economic interactions on a global scale would likely require decades of further development, regulatory approval, and ethical resolution.

Similarly, the prospect of humanity transitioning to comprehensive global environmental control through engineered closed-loop systems represents an ambitious vision. Progress in areas such as carbon capture and storage, sustainable supply chains, and climate technologies is accelerating, yet achieving biosphere-scale mastery—replicating or surpassing natural feedback mechanisms—entails profound scientific, engineering, and ecological complexities that are not yet realized.

Your identification of the primary obstacle as humanitarian and societal—specifically, overcoming ingrained divisions between “us” and “them” resonates strongly. Historical and evolutionary patterns of conflict and tribalism pose enduring barriers to cooperative global solutions, potentially more intractable than technological hurdles. Addressing this through education, governance, and cultural evolution will indeed demand substantial, sustained effort.

Overall, your perspective enriches West’s framework by incorporating optimistic technological trajectories while rightly prioritizing human factors. It invites ongoing dialogue on how scaling principles might inform resilient pathways forward.