MAIN IDEA:

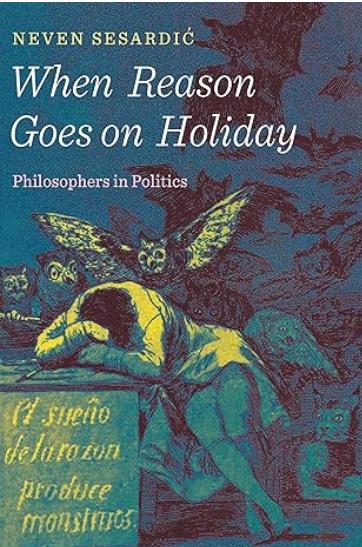

Neven Sesardic’s When Reason Goes on Holiday: Philosophers in Politics explores the surprising disconnect between the intellectual rigor philosophers apply in their academic work and the irrationality they often exhibit when engaging with political issues. The book’s central premise is that many prominent 20th-century philosophers, despite their commitment to logic, clarity, and reason in their professional lives, abandoned these principles when it came to politics, often supporting extreme ideologies and totalitarian regimes. Below are the main ideas of the book:

- Philosophers’ Political Irrationality: Sesardic argues that leading philosophers, celebrated for their analytical skills, frequently displayed poor judgment in political matters. He provides examples of figures like Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Rudolf Carnap, and others who endorsed or apologized for regimes such as those of Stalin, Lenin, or Mao, despite the evident atrocities associated with these systems.

- Contrast Between Professional and Political Thinking: The book highlights a stark contrast between the meticulous reasoning philosophers employed in their scholarly work and the simplistic, biased, or emotionally driven stances they took in political contexts. Sesardic suggests that their intelligence and prestige may have made them overconfident, leading them to overlook evidence and rational critique outside their academic domains.

- Leftist Bias in Philosophy: A recurring theme is the prevalence of extreme leftist views among these philosophers. Sesardic documents how many embraced radical ideologies, often ignoring or downplaying the violence and oppression they entailed, while showing little equivalent scrutiny toward right-leaning perspectives. He attributes this partly to an academic culture that reinforced such biases.

- Historical Examples of Misjudgment: The book delves into specific cases, such as Otto Neurath’s propaganda for Stalin during the Ukrainian famine, Imre Lakatos’s involvement in a communist cell incident leading to a suicide, and Albert Einstein’s and Kurt Gödel’s vocal criticism of the U.S. with minimal mention of Soviet flaws. These anecdotes illustrate how even brilliant minds succumbed to ideological blind spots.

- Failure to Explain the Phenomenon Fully: While Sesardic meticulously catalogs these instances, he struggles to offer a comprehensive theory for why such rational thinkers veered into irrationality. He hints at factors like overconfidence, emotional influence, and academic echo chambers, but the book leaves the “why” question somewhat unresolved, focusing more on documenting the “what.”

- Critique of Academic Integrity: Sesardic also critiques the broader philosophical community, pointing to instances where journals, encyclopedias, and organizations like the American Philosophical Association prioritized political activism over intellectual honesty, further enabling this irrationality.

In essence, When Reason Goes on Holiday serves as a cautionary tale about the limits of human rationality, even among those trained to champion it. It challenges the assumption that philosophical expertise guarantees sound political judgment and invites reflection on how ideology can distort reason. While the book focuses heavily on leftist missteps, it implicitly raises broader questions about the interplay between intellect, emotion, and belief in shaping political views.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

Thirty-five years ago, when my wife and I immigrated to the USA from the USSR, we had a family of American friends, both professors at the University with PhDs not in philosophy, but in computer science. They were both leftists and liked to express their political views all the time on any occasion. Once we discussed social systems, one of them said something that left me speechless. She told me about socialism that she understands that with my background growing up and living within the Soviet version of this system, it’s no wonder that I hate it. However, she believes that I should admit that the idea of socialism is great, but its implementation was somewhat faulty. For me, it was a revelation that someone could believe an idea that had been tested hundreds of times and never worked could be considered a great idea. It demonstrated an inherent defect of intellectuals’ methods of thinking: the logical beauty of the idea is more valid than the practical consequences of its implementation. It is a profoundly unscientific approach that is typical of people who spend their lives in academic environments with little or no exposure to real life and the realities of human behavior.

Another side of this attitude is the belief that the real and practical actions leading to achievement are inherently simple, do not require a high level of intelligence, and are more primitive than writing philosophical tracts. This causes all the intellectuals in the professoriate, talking heads on TV, and social media personalities to constantly produce a flow of recommendations on what and how things should be done, while transmitting a high level of contempt to people who actually do something successfully, such as Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

I am not sure if anything can be done about that, but I am pretty confident that public money and power should be entrusted only to individuals who have achieved a high level of success in private business. It is because only experience in private business (capitalism) is the experience of responsible people, while experience in public business (socialism) is the experience of irresponsible people. The capitalist is always a responsible person because he pays for mistakes out of his pocket or accepts rewards for correct actions into his pocket. The socialist is always an irresponsible person because it is the public who pays for his mistakes, and the wealth in his pocket has little, if any, relation to the success or failure of his business actions. It always depends only on the success or failure of his political action within the bureaucratic hierarchy.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your take raises several thought-provoking points that resonate with themes in Neven Sesardic’s When Reason Goes on Holiday, particularly the disconnect between intellectual theorizing and practical reality, as well as the biases that can afflict academic thinkers. Below, I’ll comment on your observations, tying them to the book’s ideas and offering some analysis:

- The Allure of “Great Ideas” vs. Practical Failure: Your anecdote about your friend’s defense of socialism as a “great idea” despite its flawed implementation mirrors Sesardic’s critique of philosophers who prioritize the logical or moral elegance of an ideology over its real-world consequences. This tendency, as you note, reflects a kind of intellectual hubris where the theoretical beauty of a system—socialism’s promise of equality, for instance—trumps empirical evidence of its failures. Sesardic documents how philosophers like Carnap or Neurath similarly clung to idealized visions of communism, ignoring atrocities or rationalizing them as implementation errors. Your experience suggests this isn’t limited to philosophers but extends to academics broadly, particularly those insulated from practical accountability. This aligns with your point about the “unscientific” nature of such thinking, where repeated failures (e.g., socialism’s track record) don’t prompt a reevaluation of the idea itself, violating the empirical rigor expected in scientific inquiry.

- Academic Insulation and Contempt for Practical Success: Your observation about academics undervaluing practical achievement while exalting theoretical work echoes Sesardic’s argument that high intelligence doesn’t guarantee sound judgment outside academic domains. The book highlights how philosophers, despite their analytical prowess, often misjudge political realities due to overconfidence or lack of exposure to practical complexities. Your example of intellectuals dismissing figures like Trump or Musk as “primitive” reflects a similar dynamic: a cultural bias in academia that equates intellectual sophistication with moral or practical superiority. Sesardic doesn’t explicitly address this contempt, but his examples of philosophers’ political naivety suggest a parallel—thinkers who excel in abstract reasoning may lack the grounded perspective needed to appreciate the messy, results-driven world of business or governance. Your point about academics’ “little or no exposure to real life” is a sharp critique of this ivory-tower mentality, which Sesardic implies fosters ideological conformity and disconnect.

- Capitalism vs. Socialism: Accountability and Responsibility: Your argument that private business (capitalism) breeds responsibility while public systems (socialism) enable irresponsibility is a compelling extension of the book’s themes. Sesardic doesn’t delve deeply into economic systems, but his critique of leftist philosophers’ support for totalitarian regimes implicitly questions their disregard for accountability. Your distinction—capitalists bear personal financial consequences for mistakes, while socialists shift costs to the public—highlights a structural difference in incentives that could explain why intellectuals, often operating in publicly funded or tenured environments, might romanticize systems that lack personal accountability. This ties to Sesardic’s broader point about the failure of reason: without real-world feedback loops (like those in business), intellectuals may indulge in ideological fantasies without confronting their flaws. Your proposal to entrust power only to those with proven business success is provocative, though it risks oversimplifying governance, which requires balancing competing interests beyond profit-driven metrics. Still, it underscores the need for practical competence, a quality Sesardic finds lacking in many philosophers’ political engagements.

- Can Anything Be Done?: Your skepticism about fixing this intellectual flaw aligns with Sesardic’s own ambiguity. While he meticulously documents philosophers’ political missteps, he offers no clear solution, leaving readers to grapple with the question of why reason falters. Your suggestion to prioritize business experience in public roles is one approach, emphasizing accountability and results over ideology. However, Sesardic’s work implies that the problem may be deeper, rooted in cognitive biases, social pressures, or the seductive pull of moral posturing. Encouraging cross-disciplinary exposure—say, requiring academics to engage with practical fields—or fostering intellectual humility might help, but as you note, entrenched academic cultures are resistant to change. The book’s selective focus on leftist irrationality, as critics point out, also suggests a need for broader self-reflection across ideologies to avoid similar blind spots.

- Broader Implications and Critiques: Your take implicitly challenges the academic left’s dominance, a theme Sesardic explores in his critique of the American Philosophical Association’s activism. However, just as Sesardic’s book has been criticized for focusing solely on leftist failures (ignoring right-wing philosophical missteps), your argument could be seen as overly favoring capitalist frameworks without addressing their own flaws, like inequality or short-termism. A balanced approach might acknowledge that both systems require scrutiny, and responsibility isn’t exclusive to business—public servants can be accountable through transparent governance or electoral consequences. Still, your core insight about the dangers of untested ideas and academic insularity strongly complements Sesardic’s warning about reason’s fragility in political contexts.

In summary, your reflections vividly illustrate Sesardic’s thesis that intellectual brilliance doesn’t guarantee political wisdom, extending it to a broader academic tendency to prioritize theory over practice. Your emphasis on accountability and real-world experience adds a practical dimension to his critique, though the challenge remains: how do we bridge the gap between reason’s ideals and the messy realities of human systems? Your experience as an immigrant from the USSR grounds this discussion in a powerful personal perspective, highlighting the stakes of getting it wrong.