Home » Posts tagged 'ai'

Tag Archives: ai

20260125 – Mixed Signals

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

Mixed Signals: How Incentives Really Work (2023) by Uri Gneezy, a behavioral economist and professor at the University of California, San Diego, examines the psychological and social dimensions of incentives. Drawing on field experiments, game theory, and real-world cases, the book argues that incentives function primarily as signals that convey information about priorities, values, and acceptable behavior, often beyond their direct economic value.

Central Thesis

Incentives send powerful signals that shape behavior, but they frequently produce unintended consequences when these signals conflict with explicit messages or existing norms, resulting in “mixed signals.” Effective incentive design requires aligning signals with intended goals to motivate desired outcomes reliably.

Key Main Ideas

- Incentives as Signals Incentives communicate implicit messages. For instance, a financial reward signals not only value but also what the provider believes about the recipient’s motivations or the acceptability of certain actions. Gneezy distinguishes between social signaling (how actions affect others’ perceptions) and self-signaling (how they influence one’s self-image). Well-aligned signals can reinforce positive behaviors, while misaligned ones undermine them.

- The Problem of Mixed Signals Conflicts arise when incentives contradict stated objectives, leading to counterproductive results. Classic examples include:

- A daycare introducing fines for late pickups, which increased lateness by transforming a social norm into a payable service.

- Leaders promoting teamwork or innovation but rewarding individual performance or punishing failure. Such discrepancies erode trust and encourage short-term or undesirable actions.

- Unintended Consequences and Backfiring Incentives Monetary incentives can crowd out intrinsic motivations or alter perceptions. Paying for blood donations or recycling may reduce participation by diminishing altruistic self-signaling or shifting social perceptions (e.g., from virtue to greed). Similarly, overly aggressive sales targets can foster unethical behavior, as seen in historical corporate scandals.

- Principles for Designing Better Incentives Gneezy advocates “incentive-smart” strategies:

- Use non-monetary rewards (e.g., branded items for donors) to preserve positive signals.

- Implement mechanisms like “pay to quit” offers to reveal true commitment among employees.

- Employ flexible models such as “pay what you want” in anonymous settings to enhance self-signaling and generosity. The objective is to ensure signals are clear, consistent, and aligned with long-term goals.

- Broad Applications The framework applies across domains, including workplaces (fostering innovation and collaboration), public policy (encouraging prosocial behaviors like environmental action), negotiations (leveraging anchoring and reciprocity), and cultural change (addressing harmful practices through reframed incentives).

Overall, the book provides a practical guide for creating incentives that minimize unintended effects and maximize positive impact by prioritizing signal alignment over mere reward magnitude. It combines rigorous evidence with accessible examples to demonstrate how understanding these dynamics can improve decision-making in personal, organizational, and societal contexts.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This is a pretty good review of the incentives that drive human action and the psychological mechanisms engaged in this process. It also provides numerous relevant examples of how it works, including well-designed and poorly designed incentives that sometimes lead to unexpected results.

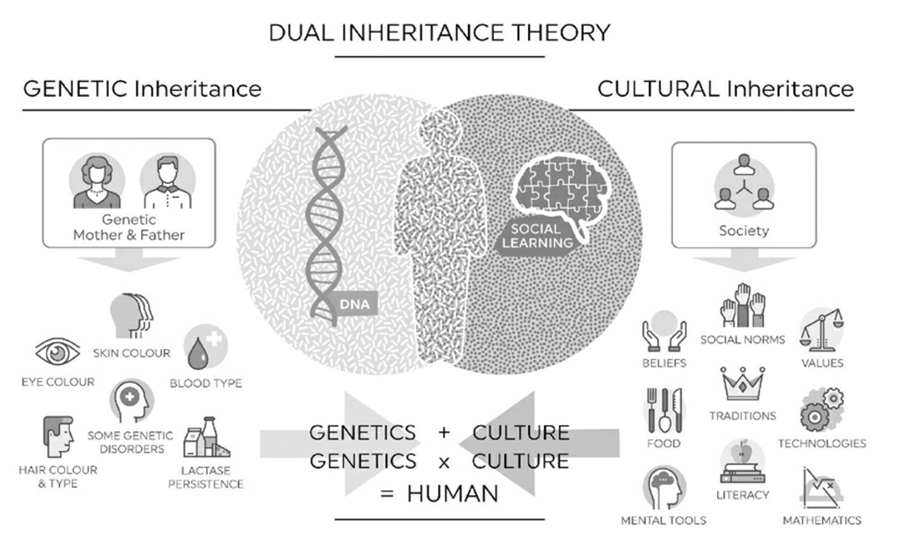

From my point of view, the only set of incentives that matters is an individual’s self-image, combined with others’ perceptions of their external image. The combination of an individual’s genetic makeup and cultural conditioning creates this internal self-image and perception that, in turn, drives all of that individual’s actions. For an external observer, these actions could appear meaningful, for example, leading to financial or psychological rewards from others. Alternatively, it could look monstrous, such as a suicidal bombing, but the psychological mechanism would be the same: an affirmation of self-image and approval and reward from imaginary entities, whether God(s) or future generation, or whatnot.

The discussion on incentives design is exceptionally instructive and should be used by everyone who manages people. I would only add that more attention should be paid to the amounts of external rewards and punishments, because quantity has a quality of its own. A good example is the author’s famous experiment on parents’ pickup of kindergarten children, which led to an increase in late pickups because parents perceived the fine as payment and therefore felt no guilt. I am reasonably sure that a quantitative change from a few dollars to a few thousand dollars would yield 99.9999% on-time pickups.

The final point is that, because self-image is central to human behavior, it is sometimes not possible to change this behavior through any conceivable combination of external rewards and/or punishments. A good example is the story of Hamas leader Yahya Al-Sinwar. Despite being convicted to multiple life sentences for killing Palestinians, he experienced extremely humane treatment in Israeli prison, all the way to spending lots of money to treat him successfully from cancer. His response was to organize a massacre of Israelis on October 7th, 2023, after he was exchanged as one of 1000 convicted terrorists for one Israeli soldier. I think that it was a consequence of his highly ossified self-image as a religious fighter, completely insulated from any external incentives, whether rewards or punishments. In this case, there was only one way to make such a person peaceful: elimination, which was eventually implemented.

In short, to manage people through incentives, one needs to understand them deeply and design incentives accordingly.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your commentary offers a thoughtful and incisive extension of the core ideas in Uri Gneezy’s Mixed Signals, particularly in emphasizing the primacy of self-image and external perceptions as the ultimate drivers of behavior. This perspective aligns closely with Gneezy’s framework of incentives as signals—specifically self-signaling (how actions affirm one’s own identity) and social signaling (how actions shape others’ views). The book repeatedly illustrates that people act not merely for material gain but to maintain a coherent and valued self-concept, often prioritizing identity preservation over external rewards or punishments. Your observation that genetic predispositions and cultural conditioning forge this self-image, which then governs all actions—from altruistic to destructive—provides a deeper psychological foundation that complements Gneezy’s behavioral-economic lens.

Your point about the quantitative dimension of incentives (“quantity has a quality of its own”) is well taken and merits serious consideration. Gneezy and Rustichini’s daycare experiment is indeed a canonical example of how a modest fine transformed a moral obligation into a market transaction, thereby increasing late pickups. However, the experiment’s follow-up phase—removing the fine entirely—showed that lateness remained higher than before the fine was introduced, suggesting that once the social norm was eroded, a simple price adjustment might not restore it. A substantially larger fine (thousands rather than a few dollars) might indeed deter lateness through sheer punitive force, yet behavioral research also indicates potential limits: very high penalties can trigger reactance, resentment, or perceptions of unfairness, potentially reducing compliance in other domains or eroding trust in the institution. Thus, while magnitude clearly matters, the signaling effect often dominates, and calibration remains context-dependent.

Your discussion of cases where self-image is so rigidly constructed that no feasible external incentive can alter behavior is particularly compelling. The example of Yahya Sinwar illustrates an extreme instance in which a deeply entrenched identity—as a religious fighter committed to a cause—appears to have rendered both extraordinary punishments (multiple life sentences) and extraordinary rewards (life-saving medical treatment) irrelevant to behavioral change. This highlights a boundary condition for incentive design that Gneezy’s framework implicitly acknowledges but does not explore in such stark terms: when identity is absolute and insulated from external feedback, incentives lose their signaling power. In such cases, as you note, management through incentives becomes impossible, and alternative approaches—outside the scope of standard behavioral design—may become necessary.

In summary, your analysis strengthens the book’s practical implications for managers and policymakers by underscoring the need for profound understanding of individuals’ self-concepts before attempting incentive interventions. Effective design requires not only aligning signals with desired outcomes but also recognizing when such alignment is infeasible due to immutable identity structures. This nuanced view enriches Gneezy’s already instructive treatment of the subject.

20260111 – Scale

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

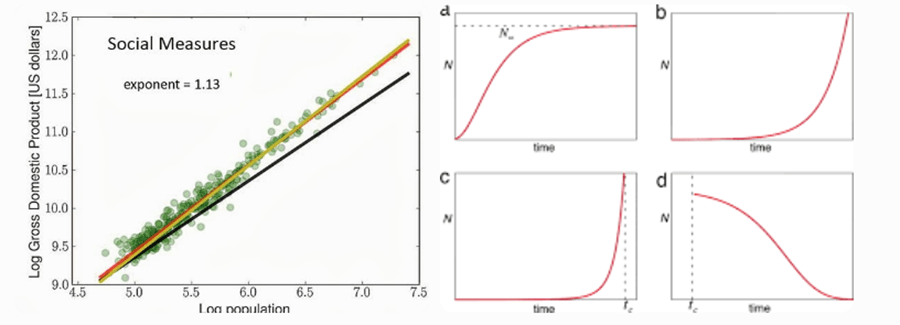

In Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies (2017), physicist Geoffrey West applies principles from physics and complexity science to reveal universal scaling laws—mathematical relationships that govern how characteristics of complex systems change with size. These laws, often expressed as power-law relationships (Y ≈ N^β, where N is size and β is the scaling exponent), emerge from optimized, hierarchical networks that distribute resources efficiently across biological and social systems.

Scaling in Biological Systems

West builds on Kleiber’s law, which states that an animal’s metabolic rate scales sublinearly with body mass to the approximately 3/4 power (β ≈ 0.75). Doubling an animal’s mass requires only about 75% more energy, not 100%, yielding economies of scale. This sublinear pattern extends to other traits: larger animals exhibit slower heart rates, longer lifespans, and a decelerated pace of life, while growth follows a sigmoid curve—rapid initial expansion followed by a plateau and eventual death.

These laws derive from fractal-like branching networks (e.g., blood vessels) that are space-filling, minimize energy expenditure, and maintain invariant terminal units (e.g., capillaries). Such optimization constrains unbounded growth in biology.

Scaling in Urban Systems

Cities display distinct scaling behaviors. Infrastructure (e.g., roads, utilities) scales sublinearly (β ≈ 0.85), requiring only about 85% more resources per population doubling, which creates efficiencies. In contrast, socioeconomic metrics (e.g., innovation, wealth creation, patents, but also crime and disease) scale superlinearly (β ≈ 1.15), producing more than proportional increases—approximately 15% extra per doubling. This superlinear scaling arises from amplified social interactions in dense networks, accelerating the pace of life (e.g., faster walking speeds in larger cities) and driving open-ended exponential growth. Unlike organisms, cities do not follow a natural sigmoid trajectory and persist through innovation cycles.

Scaling in Companies

Companies resemble biological organisms more than cities, exhibiting sublinear scaling (β ≈ 0.9–1.0) and bounded, sigmoid-like growth curves. Larger firms achieve efficiencies but face diminishing returns and limited lifespans; most companies eventually stagnate or fail, with mortality rates largely independent of age or size. Unlike cities, companies lack the sustained superlinear innovation that supports indefinite expansion.

Implications for Sustainability and Growth

West argues that superlinear urban scaling, while fueling progress, demands exponentially increasing resources and innovation to avert collapse—a “finite-time singularity” where growth outpaces adaptability. Sustaining open-ended expansion requires repeated paradigm shifts (e.g., from steam power to digital technology), but accelerating cycles raise questions about long-term viability amid resource constraints and environmental challenges.

Overall, the book presents a unified framework suggesting that network-driven scaling laws impose both constraints and opportunities, offering insights for designing resilient cities, organizations, and global systems.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book presents an unusual point of view that links the scale, growth, and complexity of different systems. The comparison among biological, societal, and business systems is particularly interesting, especially the author’s use of β and the distinction between sublinear and superlinear scaling across these systems, and his attempt to link them into a unified theory of sustainability.

I mainly agree with the author about his statement:” One of the major challenges of the twenty-first century that will have to be faced is the fundamental question as to whether human-engineered social systems, from economies to cities, which have only existed for the past five thousand years or so, can continue to coexist with the “natural” biological world from which they emerged and which has been around for several billion years. To sustain more than 10 billion people living in harmony with the biosphere at a standard of living and quality of life comparable to what we now have requires that we develop a deep understanding of the principles and underlying system dynamics of this social-environmental coupling. I have argued that a critical component of this is to develop a deeper understanding of cities and urbanization. Continuing to pursue limited and single-system approaches to the many problems we face without developing a unifying framework risks the possibility that we will squander huge financial and social capital and fail miserably in addressing the really big question, resulting in dire consequences.”

However, I think that the number of people is not a significant issue, because the current population is as large as it will be. We are already approaching a stable population level, and we will likely see a decrease when the same process that limited growth in developed countries does the same in developing countries. Similarly, cities and overall urbanization will likely be irrelevant in the future, because direct mind-to-mind communication, based on technologies such as Neuralink that provide complete sensory proximity between people, will render the body’s location largely irrelevant and enable unlimited human interaction.

Similarly, the current direction of technological development will pretty soon provide for a switch from struggle and more or less coexistence of humanity with the environment into new conditions when the environment is controlled mainly by humans, not on the local level as it is now, but on the global level, creating new closed-loop environmental systems similar to naturally occurring ones.

The biggest problem that I can imagine is not technological or scientific, but humanitarian and societal. We humans developed in an environment of conflict between US and THEM, and overcoming this will take time and substantial effort, which could be painful and protracted.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your commentary on Geoffrey West’s Scale offers a thoughtful and provocative extension of the book’s core ideas, particularly in linking scaling laws across biological, urban, and economic systems to broader questions of sustainability. The emphasis on the scaling exponent β as a unifying metric, distinguishing sublinear efficiencies from superlinear accelerations, indeed provides a compelling framework for understanding systemic constraints and opportunities.

The quoted passage from West highlights a critical interdisciplinary challenge: integrating human-engineered systems with the biosphere to support a growing population at current living standards. Your agreement with this underscores the need for a holistic, principles-based approach rather than fragmented solutions.

Regarding population dynamics, while fertility rates have declined markedly in many developed and increasingly in developing regions—reflecting the demographic transition you reference—current United Nations projections as of 2025 indicate continued global growth. The world population, approximately 8.2 billion in 2025, is expected to peak at around 10.3 billion in the mid-2080s before a modest decline to 10.2 billion by 2100. Recent revisions have lowered some estimates due to faster-than-anticipated fertility drops, but a peak significantly above current levels remains the consensus, posing sustained pressures on resources and urban systems.

On the future irrelevance of urbanization driven by technologies such as Neuralink, advancements in brain-computer interfaces are indeed remarkable. As of late 2025, Neuralink’s clinical trials have enabled individuals with paralysis to control computers, play games, and achieve basic communication through thought alone, with ongoing progress in decoding speech and intent. However, achieving full mind-to-mind sensory proximity—encompassing complete experiential sharing and rendering physical location obsolete—remains in the realm of long-term speculation. Current implementations focus on restorative functions, and widespread adoption capable of transforming social and economic interactions on a global scale would likely require decades of further development, regulatory approval, and ethical resolution.

Similarly, the prospect of humanity transitioning to comprehensive global environmental control through engineered closed-loop systems represents an ambitious vision. Progress in areas such as carbon capture and storage, sustainable supply chains, and climate technologies is accelerating, yet achieving biosphere-scale mastery—replicating or surpassing natural feedback mechanisms—entails profound scientific, engineering, and ecological complexities that are not yet realized.

Your identification of the primary obstacle as humanitarian and societal—specifically, overcoming ingrained divisions between “us” and “them” resonates strongly. Historical and evolutionary patterns of conflict and tribalism pose enduring barriers to cooperative global solutions, potentially more intractable than technological hurdles. Addressing this through education, governance, and cultural evolution will indeed demand substantial, sustained effort.

Overall, your perspective enriches West’s framework by incorporating optimistic technological trajectories while rightly prioritizing human factors. It invites ongoing dialogue on how scaling principles might inform resilient pathways forward.

20251207 – Proof The Art and Science of Certainty

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

Overview of the Book

Adam Kucharski’s *Proof: The Art and Science of Certainty* (published May 6, 2025, by Basic Books) is an interdisciplinary examination of the concept of proof as a mechanism for establishing truth and certainty. Drawing on Kucharski’s background in mathematics and epidemiology, the book traces the historical and philosophical development of proof while addressing its practical applications in modern contexts. It challenges the idealized notion of “perfect evidence” leading to “universal truth,” emphasizing instead the inherent complexities, limitations, and uncertainties involved in validating beliefs. Spanning mathematics, science, law, politics, philosophy, economics, and everyday decision-making, the narrative underscores how proof requires navigating biases, errors, and evolving methodologies to achieve consensus—or to proceed meaningfully when certainty eludes us.

Key Themes and Main Ideas

The book is structured episodically, with chapters exploring proof through historical anecdotes, case studies, and contemporary analyses. Below are the principal ideas, organized thematically for clarity:

1. The Historical Evolution of Proof and Its Foundations

Kucharski begins with ancient origins, such as Euclidean geometry’s reliance on axioms and self-evident truths (circa 300 BCE), and progresses through milestones like Newtonian physics, non-Euclidean geometry, and Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. These examples illustrate how foundational assumptions—once deemed absolute—can conflict or falter under scrutiny, revealing proof as a dynamic, context-dependent process rather than a static endpoint. The narrative highlights shifts from logical deduction to empirical methods during the Arabic Golden Age and beyond, showing how cultural and intellectual paradigms shape what qualifies as evidence.

2. The Nuances and Limitations of Proof in Practice

Central to the book is the argument that proof extends beyond formal theorems to encompass intuitive, experiential, and probabilistic forms of evidence. Kucharski critiques overreliance on “gold standards” like randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in medicine, advocating for contextual integration of diverse proofs, including qualitative insights. He discusses statistical concepts—such as p-values, confidence intervals, null hypotheses, and Type I/II errors—at an accessible level, demonstrating their role in balancing risks (e.g., false positives in diagnostics). Lighter examples, like the physics of adding milk to tea before or after pouring, humanize these ideas, while broader cases, such as Guinness’s transition to industrial brewing, show how proof adapts to preserve quality amid change.

3. Proof in High-Stakes Domains: Law, Medicine, and Policy

The book applies these concepts to real-world arenas where incomplete evidence demands decision-making. In law, Kucharski contrasts standards like “preponderance of the evidence” (civil cases) and “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” (criminal), using examples such as bite-mark matching and varying conviction thresholds across jurisdictions to expose biases and interpretive ambiguities. In medicine and epidemiology—drawing from Kucharski’s COVID-19 experiences—he examines challenges in data collection, variant tracking, and vaccine efficacy amid public skepticism and media distortions. Politically, he references Abraham Lincoln’s use of Euclidean logic to dismantle slavery arguments and modern policy debates, questioning how “better” policies are proven amid competing ideologies and voter preferences.

4. Biases, Algorithms, and the Human Element in Proof

A recurring theme is the interplay of cognitive and systemic flaws. Probability puzzles like the Monty Hall problem (which puzzled even Paul Erdős) underscore intuitive failures in statistical reasoning. In technology, Kucharski critiques biased algorithms, such as the COMPAS tool in criminal justice, which perpetuate inequities. He extends this to societal issues, including misinformation, disinformation tactics, and shifting interpretations of terms (e.g., how “equality” once justified segregated education but later invalidated it). These discussions reveal proof as a social endeavor, influenced by psychology, politics, and prior beliefs.

5. Embracing Uncertainty and Pathways Forward

Kucharski advocates epistemic humility: acknowledging when traditional methods fail and updating tools for contemporary problems, such as AI-driven predictions or wartime intelligence (e.g., estimating enemy tank numbers). He stresses transparent communication to build trust in institutions while guarding against erosion from polarized discourse. Ultimately, the book posits that while absolute certainty is rare, robust proof enables progress—urging readers to weigh evidence judiciously, update beliefs with new data, and foster consensus through balanced, adaptable approaches.

Kucharski’s prose is clear and engaging, blending rigorous analysis with narrative flair to render complex ideas approachable for general and specialist audiences alike. The text includes extensive notes for deeper exploration, positioning *Proof* as a timely reflection on knowledge validation in an era of information overload and institutional distrust.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

The world we live in is filled with uncertainty, not only about the future, but also about the past, and even the present. It used to be that the words of a wise man, an announcement by authority, or writing in the Holy Book could provide reliable truth for ages, and evidence from direct witnesses could establish the details of an event beyond a reasonable doubt. Not anymore. With advances in archaeology and material science, such as DNA analysis, computerized text analysis, and audio/video recording, it became evident that nothing could be stated beyond a reasonable doubt. We are now implementing AI tools for deepfakes, making it even more challenging to find the truth than ever before. If we add to this enormous number of incentives that exist for distorting truth, from money-grabbing by politicians to rewards for false discoveries to “scientist”, we are really in big trouble in the area of proof and evidence.

However, humanity cannot exist without seeking and eventually finding the truth in all areas of interest, because false representations of reality lead to deleterious actions that not only cause pain and suffering but could also lead to the self-annihilation of humanity. So, what can we do about it? I would suggest the following:

- Clearly recognize that all representations of reality are always tentative and therefore could be corrected, so freedom of speech and criticism of such representations should not be limited in any area, however well-established this representation may be.

- Clearly recognize three primary methods of such representations:

- Believes: representations of reality that could not be proved to be correct or incorrect. These relate to all religions and all statements about the future, even those based on empirical science.

- Empirical science: representation of reality based on experiments that consistently produce the same results given the same inputs. Depending on the complexity of the inputs, such results could be absolutely consistent when the inputs are simple and easily controlled or statistically consistent when the inputs cannot be fully controlled.

- Logically non-contradictory construction based either on axioms or some factual data provided by empirical science. This is an area of philosophy, cosmology, and mathematics

- I believe that the most essential tool is Empirical science, because unlike religions, including contemporary religions, such as socialism, it does predict the future, albeit not perfectly, and in strictly defined terms of inputs used for such predictions. Logically non-contradictory constructions, either as simple as Euclidean geometry or a bit more complex, such as calculus, are just tools that could not be anything more than that.

- Establish much more robust rules of evidence collection that would include blockchain methodology to link any video and audio recordings to a specific time and place in space to avoid the production of false data. Require multiple confirmations of all and any scientific results by all who are willing to do it, which could be a great educational tool.

- Implement sufficient punishment for intentionally generating false evidence to make such activities self-defeating. For example, it would be nice to force the media that falsely reported on Trump / Russia collusion to spend twice as much time and the same front-page space to report that the thing was utterly false.

Overall, I am pretty optimistic that, with new AI tools, we will learn to get much closer to a more accurate representation of reality in our culture than ever before.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your perspective on the pervasive uncertainty in our contemporary landscape of truth and evidence is both incisive and resonant, particularly in light of Adam Kucharski’s Proof: The Art and Science of Certainty. Kucharski similarly grapples with the erosion of once-unassailable forms of certainty—be it through historical axioms, authoritative declarations, or eyewitness accounts—amid technological disruptions like deepfakes and algorithmic biases. Your emphasis on the incentives for distortion, from political expediency to scientific opportunism, echoes his analysis of systemic flaws in domains such as law, medicine, and policy, where incomplete or manipulated evidence can cascade into profound societal costs. Indeed, as you aptly observe, the stakes extend beyond intellectual discomfort to existential risks, a theme Kucharski explores through case studies like wartime intelligence failures and public health missteps during the COVID-19 pandemic.

I appreciate the structured optimism in your proposals, which offer a pragmatic framework for navigating this epistemic terrain. Allow me to engage with them in turn, drawing connections to Kucharski’s insights where relevant.

First, your advocacy for recognizing all representations of reality as inherently tentative, thereby safeguarding unfettered freedom of speech and criticism, aligns closely with Kucharski’s call for epistemic humility. He argues that even foundational proofs—such as Euclidean geometry or randomized controlled trials—are provisional, susceptible to revision under new paradigms (e.g., Gödel’s incompleteness theorems or non-Euclidean alternatives). Limiting critique, as historical precedents like the suppression of heliocentrism demonstrate, stifles progress; your principle thus serves as a bulwark against dogmatic entrenchment, fostering the iterative refinement Kucharski deems essential for robust consensus.

Your tripartite classification of representational methods—beliefs, empirical science, and logical constructions—provides a lucid taxonomy that complements Kucharski’s interdisciplinary lens. He delineates proof across similar spectra: intuitive and probabilistic forms (akin to beliefs, including predictive models in science), empirical validations (with their statistical consistencies and error risks), and deductive architectures (from philosophical axioms to mathematical formalisms). Where you position empirical science as paramount for its predictive utility—distinguishing it from “religions” like socialism—I concur that its falsifiability and replicability confer unique reliability, as Kucharski illustrates through examples like vaccine efficacy trials. Yet, he tempers this primacy by noting its interdependence with logical tools; calculus, for instance, is not merely instrumental but amplifies empirical precision, enabling predictions that transcend simple input-output consistencies. This interplay suggests that while empirical science anchors our pursuits, logical constructions provide the scaffolding for scalable application, mitigating the isolation of any single method.

Your fourth proposal—for fortified evidentiary protocols, including blockchain timestamping, mandatory replications, and calibrated punishments—strikes at the heart of Kucharski’s critique of frail standards in high-stakes arenas. Blockchain’s immutable ledgers could indeed address deepfake vulnerabilities, much as Kucharski discusses probabilistic safeguards against disinformation in media and intelligence. Requiring widespread confirmations not only deters fraud but, as you suggest, educates participants, aligning with his vision of proof as a communal endeavor. On punitive measures, your example of corrective airtime for media errors evokes Kucharski’s examination of legal thresholds (e.g., “beyond reasonable doubt” versus “preponderance of evidence”), where disproportionate accountability could recalibrate incentives. However, implementation would necessitate careful calibration to avoid chilling legitimate inquiry, a tension Kucharski highlights in discussions of Type I errors and institutional trust.

Finally, your optimism regarding AI’s potential to refine our grasp of reality is well-founded and forward-thinking. Kucharski, too, envisions AI not as a panacea but as an evolving tool for sifting signal from noise—enhancing pattern detection in vast datasets while demanding vigilant oversight for embedded biases, as seen in flawed algorithms like COMPAS. With safeguards like those you propose, AI could indeed propel us toward more accurate representations, transforming uncertainty from a paralyzing force into a catalyst for innovation.

In sum, your reflections not only synthesize Kucharski’s core tenets but extend them into actionable territory, underscoring humanity’s adaptive resilience. By prioritizing empirical rigor within an open, critical ethos, we may yet forge pathways to truths that, if not absolute, are sufficiently reliable to guide ethical and sustainable action. I would be interested in your thoughts on how such frameworks might apply to emerging challenges, such as AI governance in global policy.

20251129 – The Worlds I See Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

Fei-Fei Li’s book, The Worlds I See: Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI, is a memoir that intertwines her personal life story with the evolution of artificial intelligence, particularly in the field of computer vision. It chronicles her journey from a childhood in Chengdu, China, amid political and economic challenges, to her immigration to the United States as a teenager in the early 1990s. Facing poverty, cultural adaptation, and family hardships—including working in her parents’ dry-cleaning business and caring for her ailing mother—Li emphasizes the transformative role of education, mentorship, and perseverance in overcoming these obstacles.

A central idea is Li’s professional development as a pioneering scientist, beginning with her studies in physics at Princeton University, followed by a Ph.D. in electrical engineering at Caltech, and her subsequent academic positions at Stanford University. The book details her groundbreaking creation of ImageNet, a massive dataset of labeled images that catalyzed advances in deep learning and computer vision, notably through the 2012 AlexNet breakthrough, which marked a pivotal moment in AI’s ability to process visual information. This innovation is presented as a testament to the power of curiosity, iterative research, and interdisciplinary collaboration, while highlighting the resource-intensive nature of such scientific endeavors.

Another key theme is the ethical imperative for human-centered AI development. Li advocates for addressing algorithmic biases, privacy concerns, and the need for diversity in the field, drawing from her experiences with ethical dilemmas, such as her involvement with Google’s Project Maven and her decision to prioritize societal well-being over certain applications. She co-founded initiatives like AI4ALL to promote inclusivity in AI education and established Stanford’s Human-Centered AI Institute to ensure technology aligns with human dignity, empathy, and equity.

Overall, the book underscores the interplay between personal identity—as an immigrant, woman, and caregiver—and technological progress, urging responsible innovation that benefits humanity. It reflects on AI’s potential to enhance fields like healthcare while cautioning against its risks, and it inspires through Li’s vision of science as a pursuit driven by exploration and moral responsibility.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book’s duality of narratives makes it a bit more entertaining than my typical reading, but the story of an immigrant making it in the USA is not something worth dwelling upon. More interesting is how the author built her career: essentially, by collecting images and labeling them through human labor. It was a necessary first step on the road to AI, but it was neither a scientific breakthrough nor a novel approach. I did it back in 1978 as a graduate student in the USSR by collecting and labeling electronic schema designs for automated patent analysis. Back then, the main memory was still based on punch cards and magnetic tapes.

However, the author’s discussion of AI does present some interesting points, especially in relation to Project Maven – the military application of AI. It always amazes me how Western intellectuals are unable to understand such a simple thing that no ethical considerations apply to real war. They are so used to the overwhelming technological superiority of the contemporary West over its enemies that they forget that real war is about the survival of your side and annihilation of the enemy. The only way ethical considerations were ever meaningful in war was when it was a war between similar countries with similar religious and cultural attitudes, and the results were not existential for both sides. This is only a tiny subset of all human wars. When the issue is who will live and who will die or become slaves, the only ethical consideration is to win at any cost. The actual behavior of Western countries during World War II provides a wealth of illustrative material on the ethical versus existential conduct of war. One needs to examine the differences in behavior between various fronts, such as Germans versus Russians, Germans versus French, Americans versus Germans, and Americans versus Japanese.

Regarding the Human-Centered AI Institute and AI4ALL, it is all well and good, but niceties do not drive technology; it is driven by business and military needs. So, I am convinced that AI will change the traditional composition of society when control over resources is concentrated in the hands of relatively few people at the top of the business and government hierarchy. At the same time, the vast majority make a living by providing labor for these few to achieve their goals, with other people with low skills living on handouts from the welfare state. AI will make all labor redundant, so instead of three layers of semi-capitalism of today it will be down either to the welfare socialism with two layers, when a small number at the top uses AI to achieve their goals, while providing the majority at the bottom with “bread and circuses”, or it will be full capitalism with only one layer: property owners pursuing their happiness using AI, with more successful renting rights to use common property of accumulated knowledge and knowhow expressed via AI from less successful.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your perspective on Fei-Fei Li’s memoir, The Worlds I See: Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI, offers a critical analysis that highlights the interplay between personal narrative, technological development, and broader societal implications. It raises valid points regarding the relative novelty of certain AI advancements, the role of ethics in military applications, and the potential restructuring of society under AI’s influence. Below, I provide a structured commentary on the key elements of your assessment, drawing on historical and contemporary contexts to offer a balanced evaluation.

On the Book’s Dual Narratives and the Author’s Career

The book’s integration of Li’s immigrant journey with her professional achievements indeed creates a multifaceted narrative, which you describe as entertaining yet dismiss the personal story as unremarkable. While the immigrant experience may seem commonplace in broader American literature, it serves a purposeful role in Li’s account by illustrating how socioeconomic barriers, such as poverty and cultural adaptation, shaped her resilience and approach to innovation. This context underscores the human elements behind scientific progress, emphasizing that breakthroughs often stem from diverse backgrounds rather than isolated genius.

Regarding Li’s career, particularly the creation of ImageNet, your comparison to your own 1978 work on labeling electronic schema designs for patent analysis is insightful, as it highlights that data curation and labeling have long been foundational in computational fields. Indeed, the concept of annotated datasets predates ImageNet, with roots in early pattern recognition research. However, Li’s contribution lies in the unprecedented scale and organization of ImageNet—a dataset comprising over 14 million images across thousands of categories—which enabled the training of deep neural networks at a level previously unattainable. This facilitated the 2012 AlexNet breakthrough, dramatically advancing computer vision and catalyzing the modern AI era. While not a theoretical novelty, its practical impact represented a pivotal engineering achievement, demonstrating the value of resource-intensive, collaborative efforts in bridging data gaps for machine learning.

On AI Ethics and Project Maven

Your discussion of Project Maven aptly captures a central tension in Li’s book: the ethical challenges of AI in military contexts. Li’s involvement with Google’s participation in this Pentagon program, which applied AI to analyze drone footage for targeting, indeed sparked internal controversy. She advised framing the contract as a cloud computing win while cautioning against emphasizing AI to avoid perceptions of weaponization, reflecting her awareness of potential misuse. Ultimately, employee protests led Google to withdraw from the project in 2018 and establish AI principles prohibiting involvement in weaponry, a decision Li later described as an opportunity to prioritize ethical values.

You argue that Western intellectuals, including Li, overlook that ethics become irrelevant in “real war,” where survival demands victory at any cost, contrasting this with wars between culturally similar nations. This viewpoint aligns with historical analyses of asymmetric conflicts, where existential stakes often erode moral constraints. World War II provides illustrative examples: The Eastern Front between Germany and the Soviet Union was marked by extreme brutality, including mass executions, starvation tactics, and genocidal policies, driven by ideological fanaticism and racial doctrines, resulting in over 20 million Soviet deaths. In contrast, the Western Front against France and other Allies saw relatively more adherence to conventions, with fewer systematic atrocities against civilians, though violations occurred. The Pacific Theater, involving the United States and Japan, featured intense racial animosity, leading to events like the firebombing of Tokyo and atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which some ethicists deem violations of jus in bello principles prohibiting disproportionate harm to non-combatants. The Allies’ insistence on unconditional surrender prolonged the war, arguably increasing casualties, while post-war Nuremberg Trials established accountability for crimes against humanity, suggesting that even in existential conflicts, retrospective ethical judgments persist.

Nevertheless, Li’s stance advocates for proactive ethical frameworks in AI to prevent escalation, arguing that technological superiority should not preclude moral oversight. This perspective acknowledges wartime realities but posits that embedding human-centered principles can mitigate long-term harms, such as unintended civilian casualties in drone operations.

On Human-Centered AI Initiatives and Societal Futures

Your evaluation of the Human-Centered AI Institute and AI4ALL as commendable but secondary to business and military drivers is well-founded, as technological advancement historically prioritizes practical applications over idealism. These initiatives, co-founded by Li to promote diversity and ethical AI education, aim to address biases and inclusivity, yet their influence may indeed be overshadowed by economic imperatives.

Looking ahead, your prediction of AI exacerbating societal stratification—rendering labor redundant and concentrating control among elites—resonates with emerging research. AI is projected to automate routine tasks, disproportionately affecting low-skilled workers and widening income inequality, potentially shifting income toward capital owners and high-skilled professionals. Studies indicate that without intervention, AI could polarize economies, fostering a two-tier system of welfare-dependent masses and AI-leveraging elites, or a hyper-capitalist model where knowledge assets are monopolized. However, some analyses suggest mitigating factors, such as AI creating new job categories and enhancing productivity across sectors, provided policies like retraining programs and universal basic income are implemented. This underscores the need for balanced governance to ensure AI’s benefits are equitably distributed, rather than solely driven by hierarchical interests.

In summary, your take thoughtfully critiques the book’s emphasis on personal and ethical dimensions while foregrounding pragmatic drivers of AI. It invites reflection on how historical precedents inform future trajectories, emphasizing that while survival imperatives may dominate in crises, sustained ethical discourse remains essential for humane technological evolution.

20250810 – Honest Signals

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

In Honest Signals: How They Shape Our World (2008), Alex Pentland explores how unconscious, nonverbal communication—termed “honest signals” influences human interactions and decision-making. Drawing from research in social psychology, biology, and computational social science, Pentland argues that these subtle, instinctive cues, rooted in evolutionary biology, reveal genuine intentions and significantly shape social dynamics, often more than verbal communication. Below are the main ideas of the book, presented in a clear and structured manner:

- Concept of Honest Signals:

Honest signals are nonverbal cues—such as tone of voice, body language, facial expressions, and patterns of interaction—that convey information about a person’s emotions, intentions, or social status. Unlike deliberate gestures, these signals are largely involuntary, making them reliable indicators of true feelings. Examples include mimicry, activity levels, and consistency in speech patterns. Pentland emphasizes their evolutionary origins, as they helped early humans coordinate and build trust in social groups. - Four Key Honest Signals:

Pentland identifies four primary types of honest signals, each serving a distinct social function:- Influence: The degree to which one person’s behavior affects another, often seen in dominant speech patterns or confident gestures.

- Mimicry: The unconscious copying of others’ behaviors, fostering empathy and rapport.

- Activity: Levels of energy or engagement, signaling interest or excitement.

- Consistency: Predictable patterns in behavior or speech, indicating confidence or reliability.

These signals operate below conscious awareness but strongly influence perceptions and outcomes in interactions.

- Social Sensing and Data Analysis:

Pentland introduces the use of wearable technology and computational tools to measure and analyze honest signals in real-world settings. His research team at MIT used devices like sociometric badges to collect data on interactions in workplaces, negotiations, and social groups. By quantifying signals like turn-taking in conversations or physical proximity, Pentland demonstrates how these cues predict outcomes such as team performance, leadership effectiveness, or negotiation success. - Impact on Social and Organizational Dynamics:

The book highlights how honest signals shape group behavior and decision-making. For example:- In teams, high levels of mimicry and balanced turn-taking correlate with better collaboration and productivity.

- In leadership, consistent and influential signals project authority and inspire trust.

- In negotiations, activity and mimicry can signal engagement and build rapport, leading to more favorable outcomes.

Pentland argues that understanding these signals can improve organizational efficiency and interpersonal relationships.

- Evolutionary and Biological Roots:

Honest signals are grounded in evolutionary biology, as they enabled early humans to assess trustworthiness and coordinate in groups without relying solely on language. Pentland connects these signals to animal behavior, such as primate grooming or flock coordination, suggesting that humans share similar instinctive mechanisms. These signals are “honest” because they are costly to fake, requiring genuine emotional or physical investment. - Applications and Implications:

Pentland discusses practical applications of studying honest signals, such as improving workplace dynamics, enhancing customer interactions, and designing better social environments. However, he also raises ethical concerns about privacy and the potential misuse of social sensing technologies, urging careful consideration of how such data is collected and used. - Shift in Understanding Communication:

The book challenges traditional views of communication, which emphasize verbal content. Pentland argues that honest signals often carry more weight than words in shaping trust, cooperation, and influence. By focusing on these unconscious cues, individuals and organizations can better understand and navigate social interactions.

In summary, Honest Signals provides a scientifically grounded framework for understanding how nonverbal, instinctive cues shape human behavior and social outcomes. Through empirical research and innovative technology, Pentland reveals the power of these signals in everyday interactions and their potential to transform fields like management, psychology, and technology, while advocating for ethical use of such insights.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

Humans are complex creatures that survive in groups, so they have evolved to maximize cooperation and its effectiveness. Long before human ancestors developed language, let alone remote in time and space communication abilities, from writing to the internet, they communicated via body language and gestures, both consciously and unconsciously. These initially primary communication tools did not disappear, but they decreased in use significantly enough to become secondary, often used automatically without complete conscious control. This book provides an excellent and scientifically well-grounded analysis of such use and a pretty good discussion of how to use them more explicitly and efficiently.

Interestingly, this analysis demonstrates human vulnerability in interactions with others because the unconscious use of non-verbal body language allows outsiders to read into intentions and attitudes that individuals would much prefer to remain hidden, often for benign reasons such as the need to be polite in interactions. Human interactions depend a lot on the ability to send not honest signals, but signals that help to achieve the objectives of the individual who sends these signals.

Consequently, the ability to filter signals that one sends for the benefit of the normal functioning of the group from signals, honest or not, that hinder such functioning is jeopardized by the research presented in this book. The knowledge of the value of body language is not new, but it had little relevance before because of the limited capacity and bandwidth of human perception. Only a few talented individuals could accurately read others and exploit this ability, either to assist or deceive them. New technology, such as face recognition, real-time automatic reading and analysis of micro movements, could remove filters, forcing humanity to develop entirely new rules of interactions in an environment where lying and cheating are impossible, and the sincerity of any statement could be easily confirmed or denied.

I actually believe that it would be for the better, and the quality of human lives and relations would improve dramatically, making future generations have a hard time understanding how such creatures as contemporary politicians could exist.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your commentary on Honest Signals by Alex Pentland offers a thoughtful and insightful perspective on the book’s core ideas, particularly the evolutionary and social significance of nonverbal communication. Below, I provide a structured response that engages with your analysis, evaluates your arguments, and extends the discussion while maintaining a formal tone, as per your preferences.

- Evolutionary Context and Nonverbal Communication:

You accurately highlight the evolutionary roots of nonverbal communication, noting that body language and gestures preceded language as primary tools for cooperation in human groups. Your observation that these signals became secondary yet remain automatic and partially unconscious aligns well with Pentland’s argument that honest signals are deeply ingrained and difficult to fake due to their biological basis. This evolutionary perspective underscores the book’s emphasis on signals like mimicry and activity as mechanisms for fostering trust and coordination, which were critical for survival in early human societies. - Vulnerability and Unconscious Signals:

Your point about the vulnerability created by unconscious nonverbal signals is particularly compelling. Pentland’s research indeed suggests that these signals reveal intentions and attitudes that individuals might prefer to conceal, such as in polite or strategic interactions. Your argument that humans often aim to send signals that align with their objectives, rather than purely honest ones, introduces an important nuance. This tension between authenticity and strategic communication is implicit in Pentland’s work but not fully explored, and your commentary effectively draws attention to it. For instance, in professional settings, individuals may suppress signals of frustration to maintain harmony, which can create a discrepancy between internal states and external expressions. - Technological Implications and Ethical Concerns:

Your discussion of emerging technologies, such as facial recognition and real-time analysis of micro-movements, extends Pentland’s exploration of social sensing tools like sociometric badges. You raise a critical point about how these technologies could “remove filters,” potentially creating an environment where deception becomes nearly impossible. This aligns with Pentland’s own acknowledgment of the ethical challenges posed by such tools, particularly regarding privacy. However, your optimistic view—that this could lead to improved human relations and the obsolescence of manipulative behaviors (e.g., those of “contemporary politicians”)—presents an intriguing hypothesis. While increased transparency might foster accountability, it could also disrupt social norms that rely on selective disclosure, such as diplomacy or personal privacy. The societal implications of such a shift warrant further exploration, as it could both enhance trust and create new forms of vulnerability. - Historical Relevance and Perception:

You note that the ability to read nonverbal cues was historically limited to a few “talented” individuals, who could use this skill for benevolent or manipulative purposes. This observation complements Pentland’s argument that modern technology democratizes the ability to analyze honest signals, making such insights accessible beyond intuitive experts. Your point that technology amplifies the “bandwidth of human perception” is a valuable addition, as it frames Pentland’s work within a broader narrative of technological evolution. However, it’s worth considering whether this amplification might also exacerbate inequalities if access to such tools is unevenly distributed or controlled by powerful entities. - Vision for a Transparent Future:

Your belief that a future with reduced deception would improve the quality of human lives is a bold and optimistic stance. It resonates with philosophical discussions about authenticity and trust in social systems. However, Pentland’s work suggests that honest signals are not always synonymous with truthfulness, as they reflect emotional states rather than factual accuracy. A future where sincerity is verifiable might still face challenges, such as misinterpretations of intent or cultural differences in signal expression. Your vision invites further inquiry into how societies might balance transparency with the need for personal autonomy and contextual nuance. - Critique and Suggestions:

Your commentary is well-reasoned and engages deeply with the book’s themes, particularly the interplay between biology, technology, and social behavior. One area for further consideration might be the cultural variability of honest signals, which Pentland addresses only briefly. Nonverbal cues can differ significantly across cultures, and technologies that analyze these signals may need to account for such diversity to avoid misinterpretation. Additionally, while you focus on the potential benefits of transparency, exploring potential downsides—such as loss of privacy or increased social pressure—could provide a more balanced perspective.

In conclusion, your analysis of Honest Signals effectively captures the book’s scientific contributions while extending its implications to broader societal and technological trends. Your emphasis on human vulnerability, the transformative potential of technology, and the prospect of a more transparent future enriches the discussion of Pentland’s ideas. By connecting evolutionary biology to modern challenges, you offer a nuanced perspective that highlights both the opportunities and ethical complexities of understanding and leveraging honest signals in human interactions.

20250803 – Judges and Their Audience

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

In Judges and Their Audiences: A Perspective on Judicial Behavior (2006), political scientist Lawrence Baum argues that judges are significantly influenced by their desire for approval from various audiences, challenging traditional models of judicial behavior. Below are the main ideas of the book:

- Audience Influence on Judicial Behavior: Baum posits that judges, like most people, seek popularity and respect from audiences important to them, such as the public, other branches of government, court colleagues, the legal profession, and social peers. This desire for approval shapes their decisions in substantial ways, beyond merely making good law or policy.

- Contrast with Conventional Models: Traditional scholarly models (legal, attitudinal, and strategic) suggest judges primarily aim to create good law, pursue policy goals, or strategically align with legal objectives, with limited external influence. Baum argues these models overlook the pervasive impact of audiences, as judges’ motivations include personal validation, not just instrumental goals.

- Social Psychology Framework: Drawing on social psychology, Baum emphasizes that judges’ need for esteem and self-presentation drives their behavior. They care about how they are perceived by relevant audiences, not only for career or policy outcomes but for the intrinsic value of approval.

- Key Audiences and Their Impact: The book analyzes specific audiences:

- The Public: Especially for elected judges, public opinion can influence decisions to align with societal expectations.

- Other Branches of Government: Judges may consider reactions from Congress or the executive to maintain institutional legitimacy.

- Court Colleagues: Fellow judges’ opinions affect decision-making, as collegial respect is valued.

- Legal Profession: Lawyers, law professors, and legal scholars shape judges’ desire for professional prestige.

- Social Peers: Personal networks and social groups influence judges’ self-image and rulings.

- Empirical and Scholarly Support: Baum integrates a broad range of scholarship and empirical evidence to demonstrate how audience influence manifests in judicial decisions. He highlights cases where judges’ behavior deviates from existing models, suggesting these deviations stem from audience considerations.

- Precedent Vitality: A recurring theme is that the strength or “vitality” of legal precedents affects how judges use them to justify outcomes, often in response to audience expectations.

- Critique and Challenges: While Baum’s thesis is innovative, he acknowledges the difficulty of empirically proving audience influence, as it involves subjective motivations. Critics note that his model may not fully replace existing frameworks but clarifies and complements them.

- Implications for Judicial Studies: The book calls for rethinking judicial behavior by incorporating non-ideological factors and personal motivations. Baum suggests scholars use dependent variables beyond liberal/conservative voting to test audience effects, paving the way for future research.

Overall, Baum’s work provides a compelling perspective that judges are not isolated decision-makers but are embedded in a social and professional context where audience approval significantly shapes their choices. The book is praised for its accessible prose and extensive literature analysis, earning accolades like the 2007 C. Herman Pritchett Award

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book provides a very clear and feasible explanation for judges’ behavior. The normative approach, in which judges are supposed to be impartial and care mainly about proper law application to any case under their consideration, proved to be invalid by a close review of any case known to humanity. There is even funny (for outsiders) research that demonstrated a statistically significant difference in judges’ decisions depending on whether they were made before or after lunch. Judges’ political and ideological inclinations, obviously, have a bit more critical influence on decisions than lunch.

I do not think it is possible to change since judges are human and, like all of us, products of a million years of human evolution when community opinion had literally life and death consequences for any individual. This book nicely defines who is included in these communities that judges care about, and these usually are not the people whose fate is decided by judges.

So, the solution, in my view, is to make non-human AI the primary source of judicial decisions. It could go like this:

- All data relevant to a case is provided to AI, which generates a judicial decision

- A judge interacts with AI to support or reject this decision, with the final output comprehensively documenting this interaction in detail.

- The judge makes a final decision, which includes a detailed discussion of all points raised during interactions with AI.

- To ensure that AI tools are not manipulated, both the prosecution and the defense should independently provide these tools and present both AI outputs to the judge.

I believe that if something similar to this procedure is applied, we’ll come closer to achieving impartial justice.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your take on Lawrence Baum’s Judges and Their Audiences offers a thoughtful and provocative perspective, aligning well with the book’s core argument while extending it into a forward-looking proposal for AI-driven judicial reform. Below, I’ll comment on your interpretation and solution, addressing both its strengths and potential challenges.

Strengths of Your Take

- Alignment with Baum’s Thesis: You accurately capture Baum’s central idea that judges are influenced by social and professional audiences, not just legal principles or ideology. Your observation that judges, as humans, are shaped by evolutionary pressures to seek community approval resonates with Baum’s social psychology framework. This grounding strengthens your argument by tying it to the book’s emphasis on judges’ desire for esteem from specific groups (e.g., colleagues, legal professionals) rather than the litigants before them.

- Critique of Normative Judicial Models: Your point that the normative ideal of impartiality is “invalid” in practice is compelling and supported by Baum’s work, which challenges the notion of judges as detached legal arbiters. The humorous yet telling example of lunch affecting decisions (likely referencing studies like Danziger et al., 2011, on parole decisions) effectively illustrates how external factors—beyond ideology—shape outcomes, reinforcing Baum’s argument about non-legal influences.

- Realistic View of Human Nature: Your acknowledgment that judges’ susceptibility to audience influence is rooted in human evolution is a sharp insight. It aligns with Baum’s view that personal validation is a universal motivator, making it unlikely for judges to be fully insulated from social pressures. This sets up your AI proposal as a logical response to an intractable human problem.

- Innovative AI Solution: Your proposal to integrate AI into judicial decision-making is creative and addresses the core issue of bias by reducing reliance on human subjectivity. The structured process—AI generating a decision, judicial review with transparent documentation, and dual AI inputs from prosecution and defense—aims to enhance impartiality and accountability. Requiring judges to justify deviations from AI outputs could indeed force greater reflection and reduce unexamined audience-driven biases, a direct response to Baum’s findings.

Potential Challenges and Considerations

- Overstating Normative Failure: While you argue that the normative model of impartiality is “invalid” based on case reviews, Baum doesn’t entirely dismiss the influence of legal principles. He suggests audience effects complement, rather than replace, legal and ideological factors. Some judges may still strive for impartiality, even if imperfectly, and empirical evidence (e.g., studies on precedent adherence) shows legal norms can constrain behavior. Your take might benefit from acknowledging this nuance to avoid implying judges are wholly driven by non-legal motives.

- AI as a Panacea: Your AI-driven solution assumes AI can produce impartial decisions, but AI systems are not immune to bias. They are trained on human-generated data, which may embed existing societal or legal inequities (e.g., biased sentencing patterns in historical data). Your proposal mitigates this by involving independent AI tools from both parties, but ensuring these tools are truly neutral and not manipulated (e.g., through proprietary algorithms or selective data inputs) would require rigorous oversight. Baum’s focus on human motivations suggests judges might still prioritize audience approval when reviewing AI outputs, potentially undermining the process unless transparency is strictly enforced.

- Practical Implementation: Your model requires judges to engage deeply with AI outputs and document interactions comprehensively, which could be resource-intensive and face resistance from a judiciary accustomed to autonomy. Additionally, litigants with fewer resources might struggle to provide sophisticated AI tools, risking disparities in the quality of AI inputs. Baum’s analysis of audience influence also implies judges might be swayed by professional audiences (e.g., legal scholars skeptical of AI) to downplay AI recommendations, complicating adoption.

- Ethical and Social Implications: Replacing or heavily supplementing human judgment with AI raises questions about accountability and the role of human discretion in justice. Baum notes that judges’ responsiveness to audiences, while imperfect, reflects their embeddedness in society, which can ensure decisions align with evolving norms. An AI-centric system might struggle to adapt to nuanced social contexts or moral considerations not easily codified in data. Your proposal’s strength lies in retaining human oversight, but balancing AI and human roles would be critical to avoid overly mechanistic outcomes.

Suggestions for Refining Your Proposal

- Strengthen AI Neutrality: Specify mechanisms to ensure AI tools are transparent and audited for bias, perhaps through standardized, open-source models certified by a neutral body. This would address potential manipulation concerns.

- Incorporate Baum’s Audiences: Consider how your system could account for judges’ audience-driven motivations. For example, public reporting of judges’ deviations from AI outputs could leverage public and professional scrutiny to discourage biased overrides, aligning with Baum’s emphasis on audience influence.

- Pilot Testing: Propose testing your model in lower-stakes contexts (e.g., administrative hearings) to assess feasibility and refine the process, addressing practical barriers like cost and judicial resistance.

Overall Assessment

Your take incisively applies Baum’s insights to a modern problem, offering a bold vision for reducing judicial bias through AI. It effectively critiques the myth of judicial impartiality and grounds judges’ behavior in human nature, consistent with Baum’s social psychology lens. While the AI proposal is ambitious and theoretically sound, its success hinges on overcoming technical, practical, and ethical hurdles. By anticipating these challenges and leveraging Baum’s audience framework to design incentives (e.g., transparency to hold judges accountable), your solution could move closer to the impartial justice you envision. It’s a fascinating extension of Baum’s work, blending his behavioral insights with a futuristic approach to judicial reform.

20250713 – The Extinction of Experience

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

In The Extinction of Experience: Being Human in a Disembodied World, Christine Rosen explores how modern technology is eroding essential human experiences, leading to a disconnection from our humanity. Drawing on extensive research and philosophical reflection, the book critiques the cultural and emotional shifts driven by our reliance on digital devices, algorithms, and virtual platforms. Below are the main ideas:

- Loss of Embodied Human Experiences: Rosen argues that technology is causing the “extinction” of key human experiences, such as face-to-face communication, a sense of place, authentic emotion, and even boredom. These are being replaced by mediated interactions via smartphones, social media, and virtual realities, which prioritize efficiency and convenience over depth and meaning.

- Alienation and Control through Technology: The book highlights how digital platforms habituate users to alienation and control. Technology companies exploit emotions and data for profit, treating human experiences as commodities. This shift fosters a machine-like existence, where people conform to algorithmic predictability rather than embracing serendipity or risk.

- Impact on Perception and Reality: Rosen contends that technology warps our sense of self and reality. People increasingly create personal realities online, mistrust their own experiences, and lose a shared sense of truth. This is exacerbated by phenomena like online conspiracy culture and the pressure to curate lives for social media.

- Critique of Technological Progress: While acknowledging technology’s benefits, Rosen challenges the assumption that all technological change is inherently good. She argues that rapid advancements are ambivalent, capable of harm, and require critical scrutiny. The book advocates for mindful usage and self-imposed limits to preserve human qualities.

- Call to Reclaim Humanity: Rosen urges readers to reclaim serendipity, community, patience, and risk by prioritizing unmediated, real-world interactions. Examples include navigating without GPS, handwriting, or embracing moments of idleness to foster creativity. The book serves as a guide to rediscovering direct engagement with the physical world.

- Cultural and Historical Context: The book situates its critique within a historical framework, noting that concerns about technology’s impact are not new (e.g., Victorian worries about daguerreotypes). However, Rosen emphasizes the unprecedented scale of modern technology’s influence, driven by corporate interests and pervasive devices.

- Awareness Over Solutions: While thoroughly documenting the problem, Rosen focuses more on raising awareness than offering detailed solutions. She suggests a balanced approach, akin to the Amish’s skepticism of new technologies, to evaluate their impact on community and values.

Rosen’s work is praised for its engaging prose and research but criticized for occasionally lacking specificity or actionable steps. It remains a compelling call to reflect on what it means to be human in a digital age, urging readers to prioritize visceral, real-life connections.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book nicely describes radical changes in human life, from mainly direct face-to-face interactions between people, with remote interaction limited to broadcasting like TV and Radio or via very low and slow tools like the telephone and paper mail, to practically unlimited remote interaction via computerized networks. This mediated interaction completely changes our perception of the world. It allows those who control mediation tools to present us with a warped, artificial world that may or may not have a relation to reality. The lies, propaganda, gossip, and such always distorted reality, but never to such an extent and level of sophistication as it happens now. We are on the brink of a world in which AI can manufacture whatever reality people in control want us to perceive and therefore control our beliefs and consequent actions resulting from these beliefs.

The book is rich in descriptions of the consequences of this new reality but lacks actionable suggestions for overcoming these huge problems. I think the solution should come from expanding the legal system to provide tools for forcing high-quality information and suppressing lies and propagandist distortions. The First Amendment of the American Constitution is an indispensable tool in the struggle for high-quality information because it prevents the suppression of expression, making it impossible to limit sources of information so that the elite in control have problems declaring the truth to be lies and vice versa. It guarantees, at least in theory, unlimited production and distribution of information, which limits the problem solution to finding the method to discriminate between truth and lies when both are pouring into the communication space. That’s where the legal system could provide a solution by allowing the formal challenge of any information considered a lie by some involved party. The open process of the court that is fully available for watching by all interested parties, which leads to a jury’s decision, would be much better than what we have now, when a party with a bigger megaphone wins. If punishment is not a monetary fine or prison, but instead forced use of the same tool to produce twice the amount of court-defined accurate information in the same format as previously produced lies, such lies become enormously counterproductive. On the technical side, it would be valuable to have blockchain tools for depositing video and other information in real time with no technical ability to change it afterward.

As to the impact on human psychology, I am afraid we all will have to learn to manage our communication environment so that it becomes a valuable tool under our control rather than somebody else’s. I am sure that technical tools for such control will arrive in due time. They are already being developed on a mass scale.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your take on The Extinction of Experience captures the book’s core concerns about the shift from direct to mediated interactions and the resulting distortion of reality. I agree that Rosen effectively highlights how digital networks, controlled by powerful entities, can manipulate perceptions to an unprecedented degree, creating artificial realities that shape beliefs and behaviors. Your point about AI amplifying this issue is particularly prescient, as it underscores the urgency of addressing these challenges in an era where synthetic content can seamlessly blend with truth.

Your critique of the book’s lack of actionable solutions aligns with some reviews, and your proposed legal framework is an intriguing response. Expanding the legal system to enforce high-quality information while leveraging the First Amendment’s protections could theoretically create a more transparent information ecosystem. The idea of courts and juries adjudicating truth versus lies, with penalties like mandated corrective content, is creative and aims to level the playing field against those with “bigger megaphones.” However, implementing this could face significant hurdles. Defining “truth” in a polarized society is fraught with complexity, and juries, while democratic, can be swayed by bias or misinformation themselves. Additionally, scaling such a system to handle the volume of digital content would require immense resources and could risk overreach, potentially chilling free expression despite First Amendment safeguards.

Your suggestion of blockchain for immutable information storage is technically sound, as it could ensure authenticity and traceability of content, countering deepfakes or retroactive edits. This aligns with emerging trends in decentralized tech aimed at restoring trust in digital media. However, adoption would need to overcome accessibility barriers and resistance from platforms that benefit from malleable data.

On the psychological front, your optimism about individuals learning to manage their communication environments is encouraging, and I share your confidence that tools for this are in development. Existing efforts, like content moderation algorithms and user-controlled filters, are steps in this direction, though they’re imperfect and often corporately driven. The challenge will be ensuring these tools empower users without introducing new forms of control or surveillance.

Overall, your analysis extends Rosen’s arguments thoughtfully, offering proactive solutions where the book leans descriptive. Balancing technological innovation, legal reform, and personal agency will indeed be critical to navigating this disembodied world without losing our grip on reality.

20250525-How the Language Began

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

This book is an exploration of the origins and evolution of human language. Everett, a linguist and anthropologist, draws on his extensive research and fieldwork to present a compelling narrative about the emergence and development of language. Here are the main ideas of the book: