Home » Posts tagged 'slavery'

Tag Archives: slavery

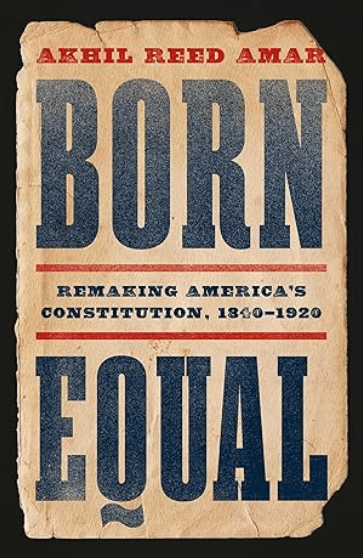

20260208 -Born Equal Remaking America’s Constitution, 1840–1920

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

The book Born Equal: Remaking America’s Constitution, 1840–1920 (published in 2025) by Akhil Reed Amar, Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale University, is the second volume in a planned trilogy on American constitutional history. It examines the transformative period from 1840 to 1920, during which the principle of birth equality—rooted in the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that “all men are created equal”—drove profound constitutional changes.

Amar’s central thesis is that this era witnessed a dramatic remaking of the U.S. Constitution through public debates, political struggles, and amendments, expanding the promise of equality from a rhetorical ideal to a practical foundation for citizenship and rights. In 1840, millions of Black Americans remained enslaved; by 1920, constitutional amendments had abolished slavery and extended citizenship and suffrage across racial and gender lines.

Key ideas include:

- Evolution of Equality: Amar traces the elaboration of birth equality by nineteenth-century thinkers and activists, who reinterpreted the founders’ words to demand broader inclusion. This vision positioned government as obligated to ensure fair opportunities for all citizens.

- Major Amendments: The narrative centers on four amendments—the 13th (abolishing slavery), 14th (guaranteeing citizenship and equal protection), 15th (prohibiting racial discrimination in voting), and 19th (women’s suffrage)—as culminations of debates over slavery, secession, emancipation, and gender equality.

- Historical Events and Debates: The book covers pivotal moments, including the Seneca Falls Convention (1848), the Dred Scott decision, Bleeding Kansas, the Lincoln-Douglas debates, the Civil War and Gettysburg Address, Reconstruction, and the women’s suffrage movement. These illustrate a nationwide constitutional conversation across public forums, Congress, and battlefields.

- Prominent Figures: Amar highlights contributions from individuals such as Abraham Lincoln (who reinvented the founders’ legacy), Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Lucretia Mott, who advanced expansive interpretations of equality.

- Constitutional Originalism: Amar frames these developments as an originalist dialogue grounded in the text and intentions of the founding documents, ultimately transforming the nation toward greater inclusivity.

Overall, the work combines legal analysis with narrative history to portray America’s challenging progress toward realizing equality, emphasizing the interplay of ideas, activism, and formal amendments.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book provides a detailed and insightful account of the struggle between two American republics: the Northern capitalist republic of free labor and the Southern, semi-capitalist republic of slave labor. The Civil War ended the Southern Republic and its slave-owning foundation de jure, but did not prevent its de facto partial restoration over the next 50 years, this time not on the basis of formal slavery but on the basis of racism and discrimination. The book also expands its coverage to another form of discrimination based on sex, which successfully achieved the demands of the suffragist movement for women’s vote, but left in place the de facto discrimination by sex in many other important areas.

The most interesting aspect of all this is the process of changing the American people’s ideology and attitudes toward both blacks and women. The multidecade process of struggle against slavery initially rested on the moral foundation for the small part of the upper classes, which concluded that it was inconsistent with their religious beliefs, and the economic foundation for the lower classes, who were threatened by the competition of slave labor. However, in the process of this struggle, more members of the upper class, such as Lincoln, changed their beliefs that blacks are biologically inferior to understanding that black as human as whites and we all belong to the human species, variations in needs for sunscreen and some statistical characteristics, both physical and intellectual, notwithstanding. Similarly, attitudes toward women have shifted from viewing them as merely a part of the family unit and denying them separate voting rights to recognizing them as individuals entitled to political representation. In both cases, direct interaction with individuals from these groups, such as Lincoln’s relationship with Frederick Douglas, black Union soldiers’ interactions with whites, and political debates with suffragists, supported this change.

However, I think the author, as a historian, paid insufficient attention to analyzing the reasons for the reconstruction’s failure and to establishing the new societal order of “separate, but equal” discrimination, rather than a purely “equal” social order.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your analysis presents a thoughtful and structurally coherent interpretation of the historical dynamics described in Akhil Reed Amar’s Born Equal: Remaking America’s Constitution, 1840–1920. It effectively highlights the tensions between competing economic systems in the antebellum United States and the persistence of discriminatory practices following formal emancipation, while also addressing parallel developments in gender equality.

The framing of two distinct “republics”—one rooted in Northern free labor capitalism and the other in Southern slave-based semi-capitalism—provides a valuable lens for understanding the sectional conflict that culminated in the Civil War. This perspective aligns with historical scholarship emphasizing the ideological and economic clash over labor systems. Amar’s account, however, places greater emphasis on a unified national constitutional conversation driven by the principle of birth equality derived from the Declaration of Independence. He traces how public debates, political activism, and key figures reinterpret this principle to expand citizenship and rights through the Reconstruction Amendments and the Nineteenth Amendment. While Amar acknowledges the profound differences between North and South, including the defense of slavery in certain Southern states, his narrative focuses more on the progressive elaboration of equality across the nation rather than a bifurcated republican model.

Your observation regarding the de facto restoration of racial hierarchy after the Civil War, succeeded by formalized discrimination under doctrines such as “separate but equal,” is well-founded. Amar recognizes the limitations of the era’s achievements, noting that constitutional protections intended to dismantle slavery were later repurposed or undermined in ways that perpetuated inequality. The book’s scope extends to 1920, encompassing the establishment of Jim Crow norms and the judicial interpretations that eroded Reconstruction-era gains. Nonetheless, as you point out, Amar’s treatment of the causes behind Reconstruction’s failure—including political compromises, violence, and shifting national priorities—receives comparatively less detailed analytical depth. His primary objective appears to be illuminating the aspirational arc toward greater inclusivity, highlighting the amendments as culminations of decades-long advocacy rather than dwelling extensively on the mechanisms of backlash and reversal.

The discussion of ideological evolution toward recognizing the full humanity of Black Americans and the individual rights of women is one of the strongest alignments with Amar’s text. He devotes considerable attention to figures such as Abraham Lincoln, whose views on racial equality deepened through personal interactions and wartime experiences, and to activists like Frederick Douglass and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who challenged prevailing attitudes via public discourse and direct engagement. Amar illustrates how interpersonal contacts, military service by Black soldiers, and suffrage debates contributed to shifting public opinion, much as you describe.

Overall, your take enriches the book’s constitutional and narrative focus with a socioeconomic dimension that underscores class interests and persistent structural inequalities. Amar’s work, as a legal and historical analysis, prioritizes the transformative power of constitutional amendments and originalist dialogue grounded in founding ideals, presenting an account that is ultimately optimistic about America’s progress toward equality, albeit incomplete. This complementary perspective invites further reflection on the interplay between formal constitutional change and enduring social realities.