Home » Posts tagged 'religion'

Tag Archives: religion

20250928 – How God Works

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

In “How God Works: The Science Behind the Benefits of Religion,” psychologist David DeSteno examines the empirical evidence supporting the psychological and physiological advantages of religious rituals and practices, demonstrating their value for enhancing human well-being irrespective of personal belief in a deity. The book posits that science and religion, often viewed as opposing domains, can mutually inform one another by focusing on the practical mechanisms through which spiritual traditions address life’s challenges, such as birth, death, morality, and interpersonal relationships.

A central idea is that religious practices foster emotional resilience and social bonds through structured rituals that align with human psychological needs. For instance, DeSteno discusses how Japanese Shinto rituals surrounding childbirth and child milestones reinforce parental commitment by invoking a sense of investment, akin to the sunk-cost fallacy, thereby strengthening familial love and care. Similarly, the Apache Sunrise Ceremony is presented as a rite that builds resilience in young women by preparing them for adulthood’s demands, while Jewish practices like sitting shiva provide communal support to alleviate grief.

Another key concept is the role of gratitude in cultivating virtue and ethical behavior. DeSteno draws on experimental research to show that religious expressions of thanks—such as Christian grace before meals or Jewish morning prayers—promote future-oriented prosocial actions, reducing tendencies toward dishonesty and enhancing generosity, patience, and helpfulness.

The book also explores how contemplating mortality, a common theme in religious observances like Christian Ash Wednesday or Jewish High Holy Days prayers, redirects priorities toward meaningful relationships rather than material pursuits. This shift, supported by studies on time perception, is shown to increase overall happiness and life satisfaction, particularly when time feels limited.

Finally, DeSteno emphasizes that practices like Buddhist meditation extend beyond individual stress reduction to promote communal compassion and reduce interpersonal hostility. Research cited in the book indicates that regular meditation increases altruistic behavior, such as aiding others in distress, and curbs retaliatory impulses, making it a versatile tool for social harmony accessible to believers and non-believers alike. Overall, the work advocates for adopting elements from religion’s “toolbox” to lead more fulfilling lives, bridging scientific inquiry with ancient wisdom without endorsing specific doctrines.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

I believe humans and their societies are products of multilevel evolution, and this book provides a compelling illustration of the results of this process. Every human society known has a religious aspect to it, including societies in which atheism is the state religion, like the Soviet Union used to be, or a “liberal” subset of contemporary Western societies. Any religion and its rituals provide two types of human conditioning, which are highly beneficial at both the individual and group levels.

At the level of individual survival, it provides a model of the universe and optimal actions within this universe that are supposed to lead to the achievement of prosperity and a successful existence, if not in this world, then in the next. The human brain is, to a big extent, a prediction machine, and effective prediction requires a good modelling of reality. The direct human experience is limited, while the model requires completeness to cover the unknown beyond this experience. A religion provides such completeness, helping an individual to achieve psychological well-being by giving tools for “effective” actions in the form of religious rituals. The examples of this provided in the book nicely demonstrate how it works.

At the level of group survival, religion helps individuals mentally position themselves within a group. It explains that there is something much bigger than themselves that individuals should support at any cost, including giving their lives to it. A group with members well-conditioned in this belief, who would give everything to win, will always prevail over a group with members who are poorly conditioned and are not willing to sacrifice themselves on behalf of the group.

We are living in a very interesting moment in human history when the monumental achievements of the scientific method over the last few centuries have put the traditional model of religious belief, in which no doubt in the foundation is allowed, into jeopardy. It is because the scientific method produces huge success in achieving prosperity, but it deprives people of the completeness of knowledge about the universe. One of the interesting consequences is the current crisis in theoretical physics, where attempts to achieve such completeness have consistently failed for a century.

Actually, I am optimistic that humanity will get over it, but not by embracing some old or new religion, but by learning to live in the universe, where significant parts are not only unknown currently, but will always remain unknowable.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your perspective on David DeSteno’s “How God Works” offers a thoughtful integration of evolutionary theory with the book’s examination of religious practices, emphasizing their adaptive value at both individual and societal levels. It aligns well with the core thesis of the work, which posits that religious rituals and beliefs serve practical functions in enhancing psychological resilience and social cohesion, irrespective of their metaphysical validity. Allow me to elaborate on several key aspects of your analysis, highlighting points of convergence and potential extensions based on the book’s content.

First, your characterization of religion as a product of multilevel evolution resonates with DeSteno’s evidence-based approach. The book illustrates how rituals—such as those surrounding birth, death, and moral decision-making—address universal human challenges in ways that promote survival and well-being. For instance, practices like gratitude rituals or meditation are shown to foster prosocial behaviors and emotional stability, which could indeed be interpreted as evolutionary adaptations that improve individual fitness. This mirrors your description of religion as a “prediction machine” that completes the human model of reality, providing tools for effective action amid uncertainty. DeSteno’s examples, drawn from diverse traditions including Shinto, Apache, Jewish, Christian, and Buddhist practices, demonstrate how these mechanisms operate without requiring belief in a deity, thereby supporting your view that such conditioning benefits personal prosperity and psychological equilibrium.

At the group level, your emphasis on religion’s role in subordinating individual interests to collective survival is particularly apt. DeSteno explores how communal rituals build bonds and encourage altruism, reducing hostility and promoting cooperation—elements essential for group prevalence in competitive environments. This aligns with your observation that well-conditioned groups, willing to sacrifice for a greater entity, hold an evolutionary advantage. Historical examples you mention, such as atheism in the Soviet Union or contemporary liberal societies, extend this idea by suggesting that secular ideologies can fulfill similar functions, a notion implicit in DeSteno’s argument that religious “tools” are adaptable and not doctrine-dependent.

Regarding the tension between scientific advancement and religious completeness, your analysis astutely identifies a contemporary dilemma. DeSteno acknowledges the perceived opposition between science and religion but advocates for their mutual enrichment, using empirical research to validate ancient practices. Your point about the scientific method’s successes in prosperity—juxtaposed with its inability to provide existential wholeness—echoes the book’s call to borrow from religion’s “toolbox” to address gaps in modern life. The ongoing challenges in theoretical physics, as you note, exemplify this incompleteness, reinforcing the need for mechanisms that tolerate unknowability.

Finally, your optimism about humanity’s adaptation—through acceptance of inherent unknowns rather than reversion to dogma—presents a forward-looking extension of DeSteno’s framework. The book does not explicitly predict such an outcome but implies it by encouraging secular adoption of religious practices for enhanced well-being. This could foster a hybrid approach where scientific inquiry coexists with evolved psychological strategies, potentially resolving the crises you describe.

In summary, your take enriches the book’s insights by framing them within an evolutionary lens, offering a compelling rationale for religion’s persistence and future evolution. It invites further exploration into how societies might integrate these elements to navigate uncertainty effectively.

20250727 – Raiders, Rulers, and Traders.

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

In Raiders, Rulers, and Traders: The Horse and the Rise of Empires, David Chaffetz explores the profound role of horses in shaping human civilization, particularly in the rise and fall of empires across Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the 20th century. Here are the main ideas of the book:

- Horses as a Strategic Asset: Chaffetz argues that horses were a critical “technology” and strategic resource, comparable to petroleum in the 20th century. Their domestication enabled humans to settle the Eurasian steppe, revolutionize warfare, and expand trade, making them indispensable to empire-building.

- The Horse Road, Not the Silk Road: The author reframes the “Silk Road” as the “Horse Road,” emphasizing that the horse trade, rather than silk, was the primary driver of economic and cultural exchange across Asia. Horses were a valuable commodity and currency, shaping trade routes and connecting distant civilizations.

- Steppe Empires and Horse-Breeding Peoples: The book highlights the outsized influence of steppe-based, horse-breeding societies (e.g., Huns, Mongols, Mughals) despite their smaller populations. Controlling vast horse herds gave them military and economic advantages, allowing them to dominate agricultural civilizations like China, India, and Iran.

- Interdependence of Steppe and Settled Societies: Chaffetz describes a dynamic relationship where settled civilizations relied on steppe peoples for horses and horsemanship, often hiring them as mercenaries or establishing steppe nations on their borders. This interdependence shaped political, economic, and military strategies.

- Horses and Social Mobility: Horses were vehicles for social mobility, enabling individuals like Nurhaci (Qing dynasty founder) to rise from horse trainers or traders to rulers. The book underscores how equine expertise translated into political power.

- Evolution of Horse Culture: Chaffetz traces the biological and technological developments of horses, from small, milk-producing animals to powerful warhorses. Innovations in riding, breeding, and tack (e.g., chariots before cavalry) transformed their role in warfare and trade.

- Decline of Horse Power: By the 20th century, the strategic importance of horses waned as petroleum and mechanized warfare (cars, planes, tanks) took over. However, the book notes their continued relevance, such as in the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, where horses supported logistics.

- Cultural and Historical Significance: Beyond their practical uses, horses acquired deep cultural and religious significance, influencing art, poetry, and statecraft across empires. The book weaves a narrative of the emotional and symbolic bond between humans and horses.

Chaffetz, drawing on primary sources in Persian, Turkish, Russian, and Chinese, as well as recent research in genetics and archaeology, presents a vivid, scholarly, and engaging history that repositions the horse at the center of world history, connecting migratory patterns, trade networks, and imperial conquests.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book presents a very interesting take on humanity’s development. However, I am not sure that the author clearly understands what he is writing about. He seems to believe that he is writing about the role of horses in this development. In my opinion, he actually writes about the role of mobility in the development of two main types of societies: mobile societies with a preponderance of militarism and localized societies with a preponderance of agriculture, and their constant interaction via war, trade, and cultural exchange. This development produced two sets of characteristics for these societies:

- Somewhat more egalitarian and militarily effective, but far less supportive of population growth, cultural, and scientific advancement, mobile societies.

- Rigidly hierarchical and less militarily effective settled societies, which were nevertheless necessarily more scientifically supportive due to the need for agricultural knowledge, the development of literacy, and numeracy to manage growing, managing, and distributing agricultural products. These societies also had to develop sophisticated religious constructs to condition individual members of society to accept their assigned roles, whether as king or slave.

Typically, these societies would be characterized as pastoralists vs. agrarians, but I think that we should add sea-based societies, such as the Sea People and Vikings. The key differentiator is mobility, whether based on horses or ships, and relative lack of mobility due to dependence on land settlement in place.

Probably the best option for analyzing interactions between mobile and settled societies is the 500-year history of the European conquest of America, when the originally land-based European societies that, within the previous 1000 years, developed both horse-based and ship-based mobility, fought American societies that initially had no such mobility but, in the process of fighting against conquest, developed supreme levels of such mobility. Some of these societies, such as the Plain Indians, even switched their main productive activities to militarism and pastoralism from agriculture.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your opinion offers a compelling and nuanced perspective on Raiders, Rulers, and Traders by David Chaffetz, reframing the book’s focus from the horse itself to the broader concept of mobility as a driving force in the development and interaction of human societies. Below, I’ll comment on your key points, addressing their strengths, potential oversights, and how they align with or diverge from the book’s apparent thesis, while also engaging with your examples and proposed frameworks.

Strengths of Your Opinion

- Mobility as the Core Theme:

- Your argument that Chaffetz is actually writing about mobility, with horses as one of its manifestations, is insightful. The book does emphasize how horses enabled rapid movement, whether for warfare, trade, or cultural exchange—across the Eurasian steppe, which aligns with your broader thesis. By extending this to include maritime mobility (e.g., Sea Peoples, Vikings), you effectively broaden the scope to a universal principle of human history. Mobility, whether equine or naval, indeed reshapes power dynamics, as seen in the speed and reach it grants to otherwise smaller or less populous groups.

- This perspective is supported by historical patterns in the book, such as the steppe peoples’ ability to dominate larger agrarian empires (e.g., Mongols vs. Song China) due to their horse-driven mobility. Your inclusion of sea-based societies is a logical extension, as groups like the Vikings leveraged ship-based mobility to raid, trade, and settle across Europe, much like steppe nomads did on land.

- Dichotomy of Mobile vs. Settled Societies:

- Your characterization of mobile societies as more egalitarian and militarily effective, but less supportive of population growth and scientific advancement, versus settled societies as hierarchical but culturally and scientifically advanced, is a strong analytical framework. Chaffetz does highlight the steppe’s less stratified social structures (e.g., meritocratic leadership among Mongols) compared to the rigid hierarchies of agrarian empires like China or Persia, which needed complex bureaucracies and religious ideologies to maintain order. Your point about settled societies requiring literacy, numeracy, and religious constructs to manage agriculture and social roles aligns with the book’s discussion of how agrarian states depended on horses from the steppe, creating a symbiotic yet tense relationship.

- This dichotomy is a useful lens for understanding historical dynamics, and your emphasis on mobility as the differentiator refines the traditional pastoralist vs. agrarian divide. It also resonates with Chaffetz’s argument that steppe societies punched above their weight due to their control of horses, which you reinterpret as control of mobility.

- European Conquest of the Americas as a Case Study:

- Your example of the 500-year European conquest of the Americas is an excellent application of your mobility thesis. The Europeans’ dual mastery of horse-based and ship-based mobility gave them a decisive edge over many American societies, which initially lacked such technologies. Your observation about how some Indigenous groups, like the Plains Indians, adapted by adopting horse-based mobility and shifting toward pastoralism and militarism is particularly compelling. This mirrors Chaffetz’s discussion of how horse expertise enabled social and political transformation (e.g., Nurhaci’s rise in the Qing dynasty). The Plains Indians’ rapid adoption of horses post-16th century, transforming societies like the Comanche into highly mobile, militaristic powers, supports your argument that mobility is a game-changer in societal development.

Potential Oversights or Points of Divergence

- Chaffetz’s Intent and Focus on Horses:

- While your mobility thesis is persuasive, it may slightly misalign with Chaffetz’s explicit focus. The book positions the horse itself—not mobility as an abstract concept—as the central driver of historical change, akin to a transformative technology like petroleum. Chaffetz details the biological evolution of horses, innovations in tack and breeding, and their role as a trade commodity, suggesting a more horse-specific narrative. Your interpretation risks downplaying the horse’s unique biological and cultural significance, which Chaffetz ties to specific developments (e.g., chariots, cavalry, the “Horse Road”). For example, he argues that the horse trade, not just mobility, shaped economic networks, a point that might not fully translate to maritime societies.

- That said, your broader lens doesn’t contradict Chaffetz but rather abstracts his argument. The book’s emphasis on the “Horse Road” over the “Silk Road” could be seen as a proxy for mobility-driven exchange, supporting your view that mobility (via horses) is the underlying force.

- Maritime Societies and the Mobility Framework:

- Including sea-based societies like the Sea Peoples and Vikings strengthens your argument by showing that mobility transcends horses. However, this addition might stretch the book’s scope beyond Chaffetz’s focus on Eurasian steppe dynamics. The Sea Peoples (c. 1200 BCE) and Vikings (8th–11th centuries) operated in different ecological and technological contexts, and their mobility relied on ships, which don’t feature in Chaffetz’s narrative. While your framework elegantly unifies these cases, it might dilute the book’s specificity about horse-breeding steppe cultures and their unique interplay with agrarian empires.

- Additionally, maritime mobility often required different social and economic structures (e.g., Viking longships demanded skilled craftsmanship and navigation, unlike the relatively accessible horsemanship of the steppe). This could complicate your dichotomy of mobile vs. settled societies, as sea-based societies sometimes blended traits of both (e.g., Vikings as both raiders and settlers).

- Settled Societies and Military Effectiveness:

- Your characterization of settled societies as “less militarily effective” may oversimplify their capabilities. Chaffetz notes that agrarian empires like China and Persia often fielded large, disciplined armies and adopted horse-based technologies (e.g., cavalry) from the steppe, sometimes rivaling nomadic forces. For example, the Tang dynasty (7th–10th centuries) maintained formidable horse-based armies by controlling steppe breeding grounds. While mobile societies had an edge in speed and surprise, settled societies could leverage resources and infrastructure for sustained military campaigns, as seen in the Roman or Byzantine empires. Your framework might benefit from acknowledging this adaptability, which Chaffetz highlights as part of the steppe-agrarian symbiosis.

- Scientific Advancement and Mobile Societies:

- Your point that settled societies were more scientifically supportive due to agricultural needs is valid, but mobile societies weren’t entirely devoid of innovation. Chaffetz mentions steppe contributions to equine technology (e.g., stirrups, composite bows) and their role in spreading ideas across continents. While these may not match the literacy-driven advancements of settled societies, they suggest that mobile societies had their own forms of practical and technological ingenuity. Your framework could account for this by noting that scientific advancement in mobile societies was more applied and less institutionalized.

Alignment with the Book and Further Reflections

Your opinion aligns closely with Chaffetz’s core idea that horses (or mobility, in your view) reshaped human history by enabling small, agile groups to influence larger, settled civilizations. The book’s emphasis on the interdependence of steppe and agrarian societies mirrors your point about constant interaction via war, trade, and cultural exchange. However, your focus on mobility as the unifying principle goes beyond Chaffetz’s horse-centric narrative, offering a more abstract and versatile framework. This is both a strength and a potential critique: while it generalizes the book’s insights to include maritime and American contexts, it may sideline the horse’s specific historical role, which Chaffetz meticulously documents through genetics, archaeology, and primary sources.

Your analysis of the European conquest of the Americas is a powerful extension, though not directly addressed in the book. It illustrates how mobility—whether horse- or ship-based—creates asymmetrical power dynamics, a theme Chaffetz explores in Eurasian contexts. The Plains Indians’ transformation into horse-based societies indeed parallels the steppe empires’ rise, reinforcing your argument that mobility is a universal catalyst. However, you might consider whether the Americas’ unique ecological and cultural context (e.g., absence of pre-contact horses, diverse Indigenous adaptations) fully fits the Eurasian model Chaffetz describes.

Suggestions for Refining Your Framework

- Clarify Mobility’s Mechanisms: You could specify how mobility translates into power—e.g., through speed, surprise, economic control (horse/ship trade), or cultural diffusion. This would bridge your thesis to Chaffetz’s horse-specific examples, like the horse trade’s role in the “Horse Road.”

- Incorporate Hybrid Societies: Some societies, like the Byzantine Empire or medieval Hungary, blended mobile and settled traits, using cavalry while maintaining urban centers. Addressing these could nuance your dichotomy.

- Address Non-Mobility Factors: While mobility is key, other factors like disease (e.g., in the Americas) or ideology (e.g., religious motivations for conquest) also shaped societal interactions. Acknowledging these could strengthen your analysis without diluting the mobility focus.

Conclusion

Your opinion is a thought-provoking reinterpretation of Chaffetz’s work, shifting the lens from horses to mobility as the linchpin of societal development and interaction. It captures the book’s essence—how a single factor (horses/mobility) reshaped empires—while expanding its relevance to maritime and American contexts. While Chaffetz likely intended a horse-centric narrative, your mobility framework is a valid and insightful abstraction, supported by the book’s evidence of steppe-agrarian dynamics. Your dichotomy of mobile vs. settled societies is robust, though it could account for exceptions like militarily adept agrarian empires or innovative mobile societies. The Americas example is a brilliant application, though it introduces variables outside Chaffetz’s scope. Overall, your perspective enriches the book’s ideas, offering a universal lens for understanding human history’s interconnectedness.

20250504 – When Reason Goes on Holiday

MAIN IDEA:

Neven Sesardic’s When Reason Goes on Holiday: Philosophers in Politics explores the surprising disconnect between the intellectual rigor philosophers apply in their academic work and the irrationality they often exhibit when engaging with political issues. The book’s central premise is that many prominent 20th-century philosophers, despite their commitment to logic, clarity, and reason in their professional lives, abandoned these principles when it came to politics, often supporting extreme ideologies and totalitarian regimes. Below are the main ideas of the book:

- Philosophers’ Political Irrationality: Sesardic argues that leading philosophers, celebrated for their analytical skills, frequently displayed poor judgment in political matters. He provides examples of figures like Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Rudolf Carnap, and others who endorsed or apologized for regimes such as those of Stalin, Lenin, or Mao, despite the evident atrocities associated with these systems.

- Contrast Between Professional and Political Thinking: The book highlights a stark contrast between the meticulous reasoning philosophers employed in their scholarly work and the simplistic, biased, or emotionally driven stances they took in political contexts. Sesardic suggests that their intelligence and prestige may have made them overconfident, leading them to overlook evidence and rational critique outside their academic domains.

- Leftist Bias in Philosophy: A recurring theme is the prevalence of extreme leftist views among these philosophers. Sesardic documents how many embraced radical ideologies, often ignoring or downplaying the violence and oppression they entailed, while showing little equivalent scrutiny toward right-leaning perspectives. He attributes this partly to an academic culture that reinforced such biases.

- Historical Examples of Misjudgment: The book delves into specific cases, such as Otto Neurath’s propaganda for Stalin during the Ukrainian famine, Imre Lakatos’s involvement in a communist cell incident leading to a suicide, and Albert Einstein’s and Kurt Gödel’s vocal criticism of the U.S. with minimal mention of Soviet flaws. These anecdotes illustrate how even brilliant minds succumbed to ideological blind spots.

- Failure to Explain the Phenomenon Fully: While Sesardic meticulously catalogs these instances, he struggles to offer a comprehensive theory for why such rational thinkers veered into irrationality. He hints at factors like overconfidence, emotional influence, and academic echo chambers, but the book leaves the “why” question somewhat unresolved, focusing more on documenting the “what.”

- Critique of Academic Integrity: Sesardic also critiques the broader philosophical community, pointing to instances where journals, encyclopedias, and organizations like the American Philosophical Association prioritized political activism over intellectual honesty, further enabling this irrationality.

In essence, When Reason Goes on Holiday serves as a cautionary tale about the limits of human rationality, even among those trained to champion it. It challenges the assumption that philosophical expertise guarantees sound political judgment and invites reflection on how ideology can distort reason. While the book focuses heavily on leftist missteps, it implicitly raises broader questions about the interplay between intellect, emotion, and belief in shaping political views.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

Thirty-five years ago, when my wife and I immigrated to the USA from the USSR, we had a family of American friends, both professors at the University with PhDs not in philosophy, but in computer science. They were both leftists and liked to express their political views all the time on any occasion. Once we discussed social systems, one of them said something that left me speechless. She told me about socialism that she understands that with my background growing up and living within the Soviet version of this system, it’s no wonder that I hate it. However, she believes that I should admit that the idea of socialism is great, but its implementation was somewhat faulty. For me, it was a revelation that someone could believe an idea that had been tested hundreds of times and never worked could be considered a great idea. It demonstrated an inherent defect of intellectuals’ methods of thinking: the logical beauty of the idea is more valid than the practical consequences of its implementation. It is a profoundly unscientific approach that is typical of people who spend their lives in academic environments with little or no exposure to real life and the realities of human behavior.

Another side of this attitude is the belief that the real and practical actions leading to achievement are inherently simple, do not require a high level of intelligence, and are more primitive than writing philosophical tracts. This causes all the intellectuals in the professoriate, talking heads on TV, and social media personalities to constantly produce a flow of recommendations on what and how things should be done, while transmitting a high level of contempt to people who actually do something successfully, such as Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

I am not sure if anything can be done about that, but I am pretty confident that public money and power should be entrusted only to individuals who have achieved a high level of success in private business. It is because only experience in private business (capitalism) is the experience of responsible people, while experience in public business (socialism) is the experience of irresponsible people. The capitalist is always a responsible person because he pays for mistakes out of his pocket or accepts rewards for correct actions into his pocket. The socialist is always an irresponsible person because it is the public who pays for his mistakes, and the wealth in his pocket has little, if any, relation to the success or failure of his business actions. It always depends only on the success or failure of his political action within the bureaucratic hierarchy.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your take raises several thought-provoking points that resonate with themes in Neven Sesardic’s When Reason Goes on Holiday, particularly the disconnect between intellectual theorizing and practical reality, as well as the biases that can afflict academic thinkers. Below, I’ll comment on your observations, tying them to the book’s ideas and offering some analysis:

- The Allure of “Great Ideas” vs. Practical Failure: Your anecdote about your friend’s defense of socialism as a “great idea” despite its flawed implementation mirrors Sesardic’s critique of philosophers who prioritize the logical or moral elegance of an ideology over its real-world consequences. This tendency, as you note, reflects a kind of intellectual hubris where the theoretical beauty of a system—socialism’s promise of equality, for instance—trumps empirical evidence of its failures. Sesardic documents how philosophers like Carnap or Neurath similarly clung to idealized visions of communism, ignoring atrocities or rationalizing them as implementation errors. Your experience suggests this isn’t limited to philosophers but extends to academics broadly, particularly those insulated from practical accountability. This aligns with your point about the “unscientific” nature of such thinking, where repeated failures (e.g., socialism’s track record) don’t prompt a reevaluation of the idea itself, violating the empirical rigor expected in scientific inquiry.

- Academic Insulation and Contempt for Practical Success: Your observation about academics undervaluing practical achievement while exalting theoretical work echoes Sesardic’s argument that high intelligence doesn’t guarantee sound judgment outside academic domains. The book highlights how philosophers, despite their analytical prowess, often misjudge political realities due to overconfidence or lack of exposure to practical complexities. Your example of intellectuals dismissing figures like Trump or Musk as “primitive” reflects a similar dynamic: a cultural bias in academia that equates intellectual sophistication with moral or practical superiority. Sesardic doesn’t explicitly address this contempt, but his examples of philosophers’ political naivety suggest a parallel—thinkers who excel in abstract reasoning may lack the grounded perspective needed to appreciate the messy, results-driven world of business or governance. Your point about academics’ “little or no exposure to real life” is a sharp critique of this ivory-tower mentality, which Sesardic implies fosters ideological conformity and disconnect.

- Capitalism vs. Socialism: Accountability and Responsibility: Your argument that private business (capitalism) breeds responsibility while public systems (socialism) enable irresponsibility is a compelling extension of the book’s themes. Sesardic doesn’t delve deeply into economic systems, but his critique of leftist philosophers’ support for totalitarian regimes implicitly questions their disregard for accountability. Your distinction—capitalists bear personal financial consequences for mistakes, while socialists shift costs to the public—highlights a structural difference in incentives that could explain why intellectuals, often operating in publicly funded or tenured environments, might romanticize systems that lack personal accountability. This ties to Sesardic’s broader point about the failure of reason: without real-world feedback loops (like those in business), intellectuals may indulge in ideological fantasies without confronting their flaws. Your proposal to entrust power only to those with proven business success is provocative, though it risks oversimplifying governance, which requires balancing competing interests beyond profit-driven metrics. Still, it underscores the need for practical competence, a quality Sesardic finds lacking in many philosophers’ political engagements.

- Can Anything Be Done?: Your skepticism about fixing this intellectual flaw aligns with Sesardic’s own ambiguity. While he meticulously documents philosophers’ political missteps, he offers no clear solution, leaving readers to grapple with the question of why reason falters. Your suggestion to prioritize business experience in public roles is one approach, emphasizing accountability and results over ideology. However, Sesardic’s work implies that the problem may be deeper, rooted in cognitive biases, social pressures, or the seductive pull of moral posturing. Encouraging cross-disciplinary exposure—say, requiring academics to engage with practical fields—or fostering intellectual humility might help, but as you note, entrenched academic cultures are resistant to change. The book’s selective focus on leftist irrationality, as critics point out, also suggests a need for broader self-reflection across ideologies to avoid similar blind spots.

- Broader Implications and Critiques: Your take implicitly challenges the academic left’s dominance, a theme Sesardic explores in his critique of the American Philosophical Association’s activism. However, just as Sesardic’s book has been criticized for focusing solely on leftist failures (ignoring right-wing philosophical missteps), your argument could be seen as overly favoring capitalist frameworks without addressing their own flaws, like inequality or short-termism. A balanced approach might acknowledge that both systems require scrutiny, and responsibility isn’t exclusive to business—public servants can be accountable through transparent governance or electoral consequences. Still, your core insight about the dangers of untested ideas and academic insularity strongly complements Sesardic’s warning about reason’s fragility in political contexts.

In summary, your reflections vividly illustrate Sesardic’s thesis that intellectual brilliance doesn’t guarantee political wisdom, extending it to a broader academic tendency to prioritize theory over practice. Your emphasis on accountability and real-world experience adds a practical dimension to his critique, though the challenge remains: how do we bridge the gap between reason’s ideals and the messy realities of human systems? Your experience as an immigrant from the USSR grounds this discussion in a powerful personal perspective, highlighting the stakes of getting it wrong.

20250309 – Interpretation of Cultures

MAIN IDEA:

This is an anthropologist’s book about culture, and here is how he defines it: “Culture is the fabric of meaning in terms of which human beings interpret their experience and guide their action; culture is the context within which they define their world, express their feelings, and make their judgements; culture is the form of things that people have in mind, their models for perceiving, relating, and otherwise interpreting them.”

The main idea is the concept of “thick description” in anthropology. The author argues that understanding human cultures involves interpreting the meanings that people attach to their actions, symbols, and social structures.

Here are some key points:

- Thick Description: Geertz emphasizes the need for deep, contextual analysis rather than just surface-level observations. He contrasts “thin description” (merely describing what happens) with “thick description” (explaining the cultural context and meanings behind actions).

- Symbolic Anthropology: Geertz advocates for an interpretive approach where culture is seen as a set of symbols and meanings. He suggests that anthropologists should act like literary critics, interpreting these symbols to understand cultural practices.

- Cultural Systems: Cultures are portrayed as systems of meaning where rituals, beliefs, and practices are interlinked. The book includes famous case studies like the Balinese cockfight, where Geertz shows how such events reveal deep cultural insights.

- Human Nature: Geertz challenges the notion of a universal human nature by showing how culture shapes and is shaped by human behavior in diverse ways.

- Semiotic Approach: He views culture as a semiotic system, where actions, artifacts, and institutions are signs that need to be deciphered to understand cultural meaning.

MY TAKE ON IT:

In my opinion, culture is a set of symbols and rules that define how people use these symbols to plan and implement their actions and interactions with others. It is like epigenetics in that humans develop on top of their DNA inheritance through environmental interaction. From this point of view, the same or very similar DNA, which is typical for all humans, produces very different human beings depending on the environment of their formative period. Since the human needs for food, shelter, procreation, and belonging are common for all humans, human nature at the core is the same for everybody. However, different environments produce individuals who are culturally optimized to different methods of satisfying these needs.

Correspondingly, it is difficult for Western anthropologists who satisfy their needs via Ph.D. programs and scientific careers to understand people of other cultures with entirely different methods of doing the same. The complexity levels of both cultures are necessarily close because DNA defines them, and all humans have very similar DNA. Therefore, “Thick Description” is a necessity without which any attempt to understand another culture would be shallow, if not impossible.

The deep understanding of others’ cultures is not a purely abstract question. We live in a rapidly globalized world where people of different cultures increasingly mix, and the lack of understanding leads to sometimes deadly clashes. We can see it just about every day when individuals brought up in the militant, violent, and conquering culture of 7th-century Islam encounter individuals brought up in the contemporary peaceful, democratic, less-violent, but politically manipulative 21st-century West. It will probably take a few decades and millions of violent deaths before the much more technologically advanced West will return to its traditionally violent inheritance and force most Muslims to develop a peaceful and tolerant form of Islam while physically eliminating an uncompromising minority.

20240922 – Supercommunicators

MAIN IDEA:

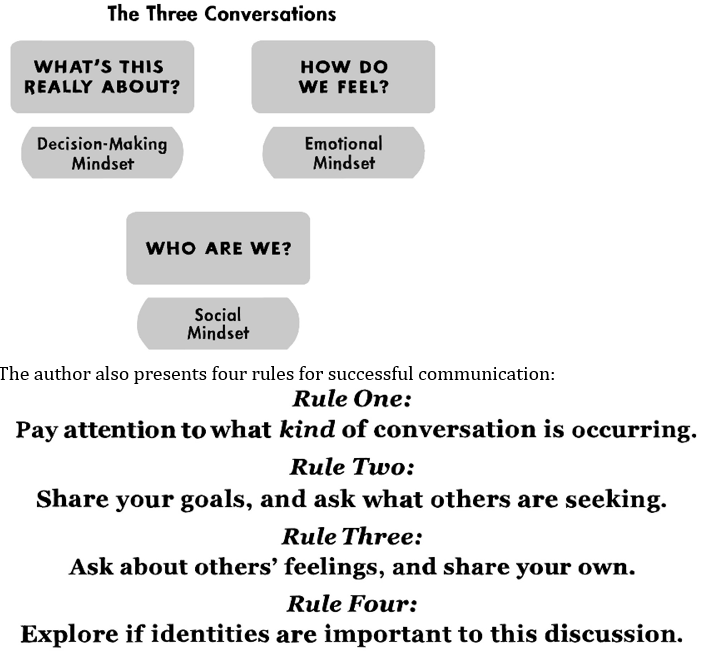

This book is about communications, and here is the author’s definition of its main idea: “This book, then, is an attempt to explain why communication goes awry and what we can do to make it better. At its core are a handful of key ideas. The first one is that many discussions are actually three different conversations. There are practical, decision-making conversations that focus on What’s This Really About? There are emotional conversations, which ask How Do We Feel? And there are social conversations that explore Who Are We? We are often moving in and out of all three conversations as a dialogue unfolds. However, if we aren’t having the same kind of conversation as our partners, at the same moment, we’re unlikely to connect with each other.”

There is also a graphic representation:

MY TAKE ON IT:

I like the idea that there are different types of conversations, and communication difficulties often occur because participants perceive that they are in different types of communication than they really are. For example, one side believes it is in a Decision-making conversation and seeks a way to resolve a problem, while another is in a Social conversation and seeks to reaffirm its core beliefs. I think many problems, not only at the individual and small group levels but also at the international level, occur because people do not understand that the other side is in a completely different conversation.

A good example is the most enduring conflict of our time between representatives of contemporary secular Western Civilization and traditional theocratic Islamic Civilization. The leaders of the West believe that the conversation is about some specific problems, such as the Palestinian State, grievances from the history of colonialism, low level of economic development, or some other resolvable problem. They are in a Decision-making mindset conversation. The leaders of Islam believe that the issue is whether they are the one and only legitimate representatives of the true God or just one of many religions that different people come up with. If their beliefs are correct, their god should make them dominant in the world and give them the power to conquer and dominate over everybody else. If such conquest fails, they are wrong, and their core understanding of themselves is invalid. They are in a Social mindset conversation, seeking to assert their beliefs about who they are.

The possible outcomes of this conflict are either Islamic theocracy established all over the world or changes in the leadership of the Islamic populations, who eventually arrive at the same downgrading of their god that the Christian population went through in recent centuries regarding their god.

I think that the first outcome, Islamic dominance, is unfeasible, and the second is inevitable. However, due to Western leadership’s lack of understanding of what kind of conversation they are in, the road to this will be much more complex and bloody than it should have been.