Home » Posts tagged 'life'

Tag Archives: life

20251004 – The Age of Choice A History of Freedom in Modern Life

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

In The Age of Choice: A History of Freedom in Modern Life, Sophia Rosenfeld examines the historical development of personal choice as a central pillar of modern conceptions of freedom, particularly in Western societies. The book traces how the ability to make choices—spanning consumer behavior, political participation, and personal identity—evolved from the seventeenth century onward and became synonymous with individual liberty. Below are the main ideas of the book, presented in a clear, structured, and concise manner:

- Choice as a Modern Definition of Freedom: Rosenfeld argues that in contemporary society, freedom is increasingly defined by the act of choosing. This conflation of choice with liberty is a historically contingent phenomenon, not a universal principle. The book explores how choice became a core component of democratic ideals, consumer culture, and personal autonomy, shaping modern notions of selfhood.

- Historical Roots of Choice: The concept of choice as a marker of freedom emerged in the late seventeenth century and developed through several domains:

- Consumer Choice: The rise of shopping as a preference-driven activity, exemplified by innovations like those of eighteenth-century London auctioneer Christopher Cock, who curated options to encourage individual selection, laying the groundwork for modern consumer culture.

- Intellectual Choice: The expansion of religious and intellectual freedom allowed individuals to choose beliefs, preachers, or texts, facilitated by practices like commonplacing (curating personal collections of ideas).

- Romantic and Social Choice: The shift toward individual agency in selecting romantic partners or social interactions, moving away from rigid societal norms, such as arranged marriages or prescribed social roles.

- Political Choice: The development of the secret ballot in the nineteenth century, which enabled private, individual decision-making in democratic processes, reinforcing the link between choice and political freedom.

- Choice and the Enlightenment: The Enlightenment period was pivotal in elevating choice as a cultural value. Philosophers and thinkers emphasized individual agency, reason, and self-determination, laying the intellectual foundation for equating choice with autonomy. Rosenfeld highlights how these ideas permeated various spheres, from markets to governance, creating a framework where choice became a measure of progress.

- Ambiguities and Tensions of Choice: While choice is celebrated as liberating, Rosenfeld examines its complexities and limitations:

- Illusion of Freedom: The proliferation of choices in consumer markets or political systems can mask structural constraints, creating an illusion of autonomy while real options remain limited.

- Overwhelm and Anxiety: The expectation to constantly make choices can lead to decision fatigue, undermining the liberating potential of choice.

- Inequality of Choice: Not all individuals have equal access to meaningful choices, as socioeconomic, cultural, and political barriers shape who can exercise agency and how.

- Choice in the Modern Era: The book explores how the twentieth and twenty-first centuries intensified the centrality of choice through mass consumption, digital technologies, and neoliberal ideologies. Rosenfeld critiques how choice is often framed as an unqualified good, despite its potential to reinforce inequality or prioritize individual desires over collective needs.

- Cultural and Political Implications: Rosenfeld underscores that the valorization of choice has reshaped societal values, prioritizing individualism over communal responsibilities. This shift has implications for democratic participation, where the focus on personal choice can sometimes undermine collective action or public welfare.

In summary, The Age of Choice provides a nuanced historical analysis of how choice became a defining feature of modern freedom, tracing its evolution across centuries and highlighting its promises and pitfalls. Rosenfeld invites readers to critically examine the cultural and political consequences of equating freedom with the act of choosing, questioning whether the abundance of choice truly enhances individual and societal well-being.

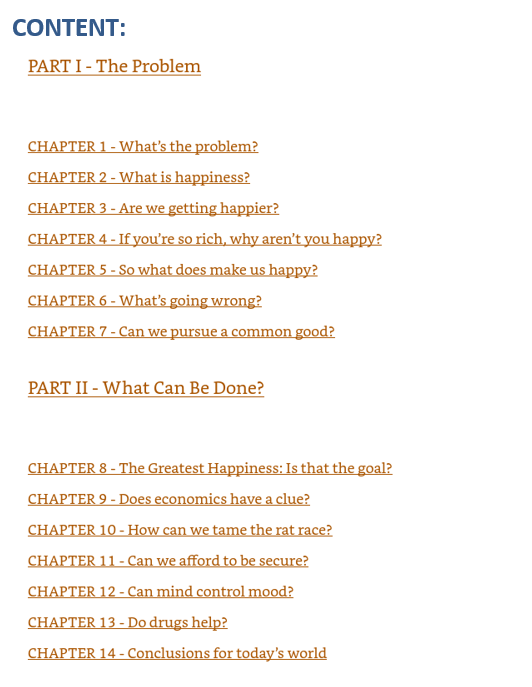

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

I believe that the conceptualization of choice as freedom is a product of the Industrial Age. It was not so before, and it will not be so when humanity moves beyond the final stages of this age. The choice is always between the options offered, while freedom is the ability to move and act as one wishes, creating new options as needed. The main characteristic of the industrial age is the generation of options for choice in the form of goods, services, and even ideas and cultural artifacts on an industrial base, meaning massive, limited, and therefore cheap.

Humans, as a product of evolution, were formed in an environment of freedom, limited only by the natural environment and communal interactions. In this environment, a vast variety of options existed, while industrially produced options are limited to a few created by human producers. A good example would be food acquisition and consumption. For hunter-gatherers, learning what is available as food, when, where, how to obtain it, and how to prepare it represents an enormous amount of knowledge developed over generations, open not only for active selection, but also for experimentation and expansion by individuals, offering significant freedom of action qualitatively different from freedom of choice between a few artificial options provided by producers. The former represents genuine freedom, while the latter represents a choice that emulates freedom but falls short of the real thing.

However, the relatively short period, spanning just a few thousand years out of millions, of humanity’s militaristic agricultural/industrial existence is coming to an end. New technologies, including AI, flexible automated production, and the availability of massive resources to each individual, will support the expansion of freedom to the extent that it not only exceeds the limited choices of the industrial age but also provides significantly larger options than those offered by natural environments. That is, if humanity will not accidentally commit suicide while playing with powerful tools beyond its understanding, much like a three-year-old playing with a chair on the balcony of a high-rise. I am relatively optimistic that it will not happen, but who knows?

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your perspective on Sophia Rosenfeld’s The Age of Choice: A History of Freedom in Modern Life offers a thought-provoking critique of the book’s central thesis, expanding on the distinction between choice and genuine freedom while situating it within a broader historical and evolutionary framework. Below, I provide a formal commentary on your take, addressing its key points and their alignment with or divergence from Rosenfeld’s arguments, while maintaining a professional and precise tone.

- Choice as a Product of the Industrial Age: Your argument that the equation of choice with freedom is a hallmark of the Industrial Age aligns closely with Rosenfeld’s historical analysis. She traces the rise of choice as a cultural value to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with the expansion of consumer markets and democratic institutions, which intensified during the Industrial Revolution. Your emphasis on the industrial production of “massive, limited, and cheap” options resonates with Rosenfeld’s discussion of how consumer culture, exemplified by curated shopping experiences, framed choice as a form of freedom. However, your point extends beyond Rosenfeld by framing this as a temporary phase, tied specifically to industrial processes, which she does not explicitly address in this way.

- Distinction Between Choice and Freedom: Your differentiation between choice (selecting from pre-defined options) and true freedom (the ability to act and move as one wishes) is a compelling critique that complements Rosenfeld’s work. She highlights the ambiguities of choice, noting that the proliferation of options can create an illusion of autonomy while structural constraints persist. Your example of hunter-gatherer food acquisition versus modern consumer choices effectively illustrates this distinction, emphasizing the qualitative difference between open-ended, experiential freedom and the constrained choices of industrial systems. While Rosenfeld does not use an evolutionary lens, your perspective enriches her argument by grounding it in humanity’s pre-industrial past, suggesting that industrial choice is a diluted form of freedom.

- Evolutionary Context and Pre-Industrial Freedom: Your reference to humanity’s evolutionary environment, where freedom was shaped by natural and communal constraints, adds a novel dimension not explicitly explored in Rosenfeld’s book. She focuses on the historical emergence of choice within Western modernity, particularly from the Enlightenment onward, without delving into pre-agricultural societies. Your point about the vast knowledge and experimentation in hunter-gatherer food systems underscores a form of agency that contrasts with the limited, producer-driven options of industrial societies. This perspective could serve as a prequel to Rosenfeld’s narrative, highlighting how the shift to agricultural and industrial systems curtailed certain forms of freedom while promoting choice as a substitute.

- Future of Freedom in a Post-Industrial Era: Your optimism about emerging technologies—such as AI and flexible production—enabling a return to expansive freedom beyond industrial constraints introduces a forward-looking dimension absent from Rosenfeld’s historical focus. She critiques the modern valorization of choice but does not speculate extensively on future transformations. Your vision of technology providing “much larger options than those provided by natural environments” aligns with contemporary debates about post-scarcity economies but raises questions about accessibility and equity, which Rosenfeld touches on in her discussion of unequal access to choice. Your caution about humanity’s potential for self-destruction with powerful technologies echoes her concerns about the unintended consequences of prioritizing individual choice over collective well-being.

- Potential Risks and Optimism: Your metaphor of humanity as a “three-year-old playing with a chair on the balcony of a high-rise” vividly captures the risks of technological advancement, a theme Rosenfeld does not directly address but which complements her skepticism about the unqualified benefits of choice. Your relative optimism about avoiding catastrophic outcomes contrasts with her more critical tone, as she questions whether the modern obsession with choice truly enhances freedom or merely perpetuates new forms of dependency and inequality.

In conclusion, your take on The Age of Choice enriches Rosenfeld’s analysis by situating the rise of choice within an evolutionary and industrial framework, distinguishing between choice and true freedom, and projecting a post-industrial future where technology could expand human agency. Your perspective aligns with her critique of choice as a limited proxy for freedom but extends it by considering pre-industrial and future contexts, offering a broader temporal scope. The tension between your optimism about technological potential and Rosenfeld’s caution about the pitfalls of choice invites further reflection on how humanity might navigate the transition to a post-industrial era while preserving genuine freedom.

20240323 Junger, Sebastian-Tribe

MAIN IDEA:

This book is about the human need to belong to some group of humans – a tribe. The author defines it this way:” Robert Frost famously wrote that home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in. The word “tribe” is far harder to define, but a start might be the people you feel compelled to share the last of your food with.” The author describes how the evolutionary developed norms of the human tribe proved to be a much better environment for human thriving than norms developed by militaristic/agricultural civilization. The author uses the historical example of interaction between societies representing these two norms: American Indian tribes and American European Settlers. This example clearly demonstrates the superiority of the norms of American Indian tribes by retelling stories of individuals who moved between these societies. On many occasions when settlers, either children or adults, were captured by Indians and accepted into a tribe, there were very few cases when these individuals wanted to return back to European society. The tribal way of life was clearly preferable. After that, the author discusses why this is the case and concludes that humans feel uncomfortable or, as he put it in a postscript: “Just dead inside” without belonging to a tribe and correspondingly sharing resources with other members of the tribe.

MY TAKE ON IT:

I think that the description of human nature provided in

this book is correct – humans do need to belong to a tribe and are miserable

when they are on their own in life. However, a lot of human life is also

defined by attitude toward other tribes, which evolutionarily developed to be

hostile by default because another tribe nearby was always a competitor for

limited resources. So, humans need both other members of their own tribe to

give life for and people who belong to other tribes to fight and kill. Without

friends and enemies, humans feel a void inside. The sad history of the clash of

Indian tribes and European tribes is a very good illustration.

Indian tribes were better adjusted to human nature in an

environment of relative abundance of natural resources when the survival of

individuals and groups was mainly dependent on effective interaction with the

environment. The European tribes were better adjusted to military competition

between groups when survival was obtained at the expense of the misery of

individual lives. As a result, the European tribes nearly completely eliminated

Indians, as it happened many times before when militaristic/agrarian societies

eliminated hunter/gatherers despite providing an inferior quality of life for

individuals.

On the bright side, humanity is now moving to form a global

tribe when all humans are included, and a superabundance of resources makes

military competition meaningless. It is not an easy process, which will take

decades or maybe even a century or two because one of the legacies of human

militaristic/agricultural societies is the psychological need to suppress

others and control them. Whether this need is expressed via the expansion of

the bureaucratic machinery of the big and deep state, via the religious

extremism of Islamists, or through activities of white or black supremacists,

it will have to be eliminated. Only after eliminating individuals who act

according to these views will humanity be able to move to a better place when

psychological comfort provided by tribes of hunter/gatherers will be combined

with the material comforts of technological civilization. Such elimination

could be psychological when individuals decide that they will be better off

without the ability to control others in exchange for the freedom of not being

controlled by others. However, for some, it would not be possible, so for these

cases, military and/or law enforcement options will become necessary. In either

case, it will take lots of time and struggle to get to this better place from

where we are now in human development.

20240120 – Happiness Lessons from a New Science

MAIN IDEA:

This book is about the paradox of happiness, which the author defines as the maintenance of the same level of happiness in developed countries despite the doubling of income and the implementation of many quality-of-life improving tools, from air-conditioning to the Internet. The author defines happiness this way:” Happiness is feeling good, and misery is feeling bad. At every moment we feel somewhere between wonderful and half-dead, and that feeling can now be measured by asking people or by monitoring their brains. Once that is done, we can go on to explain a person’s underlying level of happiness—the quality of his life as he experiences it. Every life is complicated, but it is vital to separate out the factors that really count. Some factors come from outside us, from our society: some societies really are happier. Other factors work from inside us, from our inner life.”

After that, the author provides what he believes are the defining factors of happiness:”

• Our wants are not given, in the way that elementary economics assumes. In fact they depend heavily on what other people have, and on what we ourselves have got accustomed to. They are also affected by education, advertising and television. We are heavily driven by the desire to keep up with other people. This leads to a status race, which is self-defeating since if I do better, someone else must do worse. What can we do about this?

• People desperately want security—at work, in the family and in their neighbourhoods. They hate unemployment, family break-up and crime in the streets. But the individual cannot, entirely on his own, determine whether he loses his job, his spouse or his wallet. It depends in part on external forces beyond his control. So how can the community promote a way of life that is more secure?

• People want to trust other people. But in the United States and in Britain (though not in continental Europe), levels of trust have plummeted in recent decades. How is it possible to maintain trust when society is increasingly mobile and anonymous?”

At the end of the book, the author provides a to-do list for society to make people happy. Here is the concise version:”

• We should monitor the development of happiness in our countries as closely as we monitor the development of income.

• We should rethink our attitude on many standard issues. (taxes, performance-related pay, mobility)

• We should spend more on helping the poor, especially in the Third World.

• We should spend more on tackling the problem of mental illness.

• To improve family life, we should introduce more family-friendly practices.

• We should subsidise activities that promote community life.

• We should eliminate high unemployment.

• To fight the constant escalation of wants, we should prohibit commercial advertising to children.

• Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we need better education, including, for want of a better word, moral education. “

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book provides a lot of valuable information about statistical, sociological, and psychological research in all areas related to happiness. It is all interesting, but I think that the key attitude compressed into “We as a society should do X to make people happy” reminds me a little bit of the old communist slogan:” With an iron fist, we’ll force humanity into the happy future.” I believe that such an approach is counterproductive for the simple reason that human life is a very dynamic process, and it is not possible to define what makes people happy at any given time. So, the role of society should be to create such arrangements that individuals are capable of obtaining all the resources they need to become happy, whether these resources are material, informational, or psychological. The role of science should be to produce information for personal use to help people understand what will make them happy and what to do to achieve it. In other words, accelerate the acquisition of life experience to minimize the difference between a 20-year-old belief of what will make him/her happy at 50 and 50-years-old being happy or not. Any other approach, when person A decides what should be done by person B for happiness and forces this action, works only to increase happiness from the exercise of power for person A at the expense of person B.