Home » Posts tagged 'economy'

Tag Archives: economy

20260215 – 1929

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

Andrew Ross Sorkin’s 2025 book, 1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History—and How It Shattered a Nation, provides a detailed narrative account of the 1929 stock market crash. Drawing on extensive historical records, personal correspondence, and previously unpublished documents, Sorkin reconstructs the events as an immersive human drama rather than a purely economic analysis.

Core Narrative Focus

The book chronicles the speculative boom of the late 1920s, the dramatic collapse in October 1929, and its immediate aftermath. It emphasizes the experiences of key figures—including bankers, speculators, politicians, and Federal Reserve officials—through a character-driven lens. Sorkin portrays the era’s larger-than-life personalities, such as Charles Mitchell of National City Bank and other Wall Street leaders, highlighting their ambitions, decisions, and interpersonal dynamics amid escalating market euphoria and subsequent panic. The narrative extends beyond the crash itself to examine political responses, banking crises, and high-profile investigations in the following years.

Central Themes

- Human Folly and Psychological Forces — Sorkin underscores greed, overconfidence, blind optimism, and fear as primary drivers of the crisis, challenging notions of rational markets and illustrating how emotional excesses fueled irrational speculation.

- Speculation and Structural Vulnerabilities — The text explores practices such as margin trading, easy credit, loose regulations, and stock manipulation (legal at the time), which amplified the boom and deepened the collapse.

- Power Dynamics and Institutional Conflicts — A recurring motif is the tension between Wall Street and Washington, depicting battles over financial influence and the limitations of policymakers in comprehending or controlling the unfolding events.

- The Illusion of Exceptionalism — Sorkin highlights the pervasive belief that “this time is different,” where disregarded warnings and dismissed skeptics contributed to catastrophe.

- Moral Complexity — Individuals are presented as flawed rather than simplistic heroes or villains, revealing contingency, misunderstanding, and the gray areas of ambition and naïveté.

Broader Implications

The book serves as a cautionary tale, offering insights into recurring cycles of financial upheaval driven by human nature. While avoiding explicit modern analogies, it implicitly draws parallels to contemporary issues, such as soaring markets and ignored risk signals, emphasizing the fragility of prosperity and the peril of unchecked excess. Sorkin concludes by advocating humility in financial systems, noting that no safeguards are foolproof against repeated crises rooted in behavioral impulses.

Overall, 1929 is praised for its vivid, novelistic storytelling, making complex historical events accessible while delivering timeless lessons on speculation, hubris, and economic vulnerability.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book presents a somewhat nontrivial approach to discussing the 1929 crash, which preceded the Great Depression. This approach focused not on economic events but on the people who drove them, their behavior, actions, and interactions. I find it interesting, but not really that important.

The main lesson from the Great Depression is that markets are just a representation of human feelings, beliefs, and attitudes toward the economy overall, specific business enterprises that go either up or down, and general optimism or pessimism about the near future. As such, all this makes market movements unpredictable and prone to emotional excesses that cause panics or overenthusiasm, which, from time to time, rise to extremes. The detailed description in the book of how it happened is very illustrative and entertaining, but does not change anything in the second main lesson, which is that it was just a crisis of liquidity, which could be easily overcome by the Fed as a provider of liquidity, limited only by sound or not-so-sound judgments of its governors.

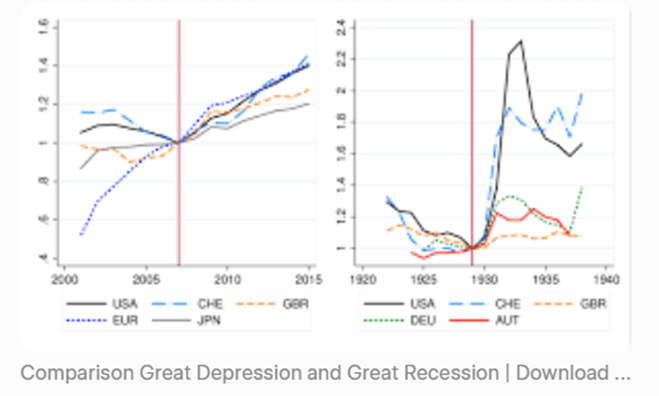

This lesson was learned well and semi-effectively applied by Ben Bernanke in 2008, which mitigated the consequences of the crash

However, another important lesson the author only slightly addresses is that governmental interference in the economy always serves the interests of those in power and should therefore be severely restricted, because these interests are always in conflict with those of those not in power.

I believe that state interference is sometimes necessary, but should be limited to the control of liquidity, a minimal safety net for individuals, not businesses, and nothing else whatsoever.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your commentary on Andrew Ross Sorkin’s 1929 offers a thoughtful and provocative interpretation, distilling the book’s narrative into a set of broader lessons about markets, human behavior, and the role of government. I appreciate the clarity with which you articulate your views. Allow me to respond to the main strands of your analysis in turn.

- The book’s human-centered approach You correctly identify that Sorkin’s primary contribution is to dramatize the crash through the ambitions, misjudgments, and interpersonal conflicts of key individuals rather than through aggregate economic data or theoretical models. You find this engaging yet ultimately unimportant. This is a reasonable judgment if one’s primary interest is in identifying actionable policy lessons or structural causes. However, the character-driven narrative serves a deeper purpose: it vividly illustrates how institutional outcomes emerge from individual incentives, blind spots, and social dynamics. By making the actors relatable—flawed, overconfident, and often self-deluded—Sorkin reinforces the behavioral foundations of market extremes without resorting to abstract psychological theory. In that sense, the approach is not merely entertaining; it is pedagogically effective for readers who might otherwise dismiss emotional drivers as irrelevant to “serious” economic analysis.

- Markets as reflections of collective sentiment Your core observation—that markets are manifestations of human optimism, pessimism, and herd behavior, rendering them inherently prone to excesses—is well supported by both historical evidence and modern behavioral finance. The 1929 episode exemplifies this: widespread margin buying, dismissal of contrarian warnings, and sudden contagion of fear produced a self-reinforcing spiral. Sorkin’s detailed reconstruction indeed illustrates this dynamic compellingly. Where we might diverge slightly is in the degree of unpredictability. While extremes are difficult to time precisely, recurring patterns of overvaluation, credit expansion, and complacency do offer warning signals that informed observers have sometimes heeded successfully.

- The liquidity-crisis interpretation and the Federal Reserve’s role You frame the crash and ensuing depression primarily as a liquidity crisis that a more accommodative Federal Reserve could have mitigated. This view aligns closely with Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s monetary hypothesis, later embraced by Ben Bernanke, who explicitly sought to avoid the Fed’s 1930s mistakes during the 2008–2009 crisis. Bernanke’s aggressive provision of liquidity through unconventional facilities did indeed prevent a complete freezing of credit markets. However, many economic historians argue that liquidity shortages were a consequence as much as a cause: bank runs, debt deflation, and collapsing confidence amplified the downturn into a prolonged depression. Thus, while enhanced liquidity provision is a critical tool—and one arguably learned from 1929—it may not constitute a complete or universally sufficient remedy for all financial crises.

- Governmental interference and its motives You raise a more normative point: that government interventions tend to serve entrenched power rather than the public interest, and should therefore be narrowly circumscribed. This perspective echoes classical-liberal and public-choice critiques of state action. Sorkin does touch on political dimensions—Hoover’s reluctance to appear interventionist, the subsequent New Deal reforms, and the Pecora hearings’ exposure of Wall Street practices—yet he stops short of a systematic indictment of government expansion. Your preference for restricting state involvement to liquidity management and a minimal individual safety net (explicitly excluding business bailouts) is internally consistent and reflects a principled commitment to limiting moral hazard and rent-seeking. Reasonable people can differ on where to draw the line; some argue that temporary, rule-based interventions in systemically critical institutions can prevent broader contagion without permanently distorting incentives. The historical record shows both successes and failures on each side of this debate.

In summary, your reading of the book extracts coherent and defensible lessons while advancing a clear philosophical stance on the proper scope of government. Sorkin’s narrative strength lies in reminding us that financial crises are, at root, human crises—driven by emotion, misjudgment, and institutional design. Whether those insights lead to confidence in central-bank liquidity tools or to deeper skepticism of state power depends, as you demonstrate, on one’s prior framework. Your analysis is a valuable contribution to that ongoing discussion.

20251116 – How the World Became Rich

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

Overview of the Book

“How the World Became Rich: The Historical Origins of Economic Growth” by Mark Koyama and Jared Rubin presents a comprehensive analysis of the factors driving sustained economic prosperity, drawing on the framework of New Historical Economics. The authors structure their argument around five key strands—geography, institutions, culture, demography, and colonialism—while emphasizing that these elements interact dynamically rather than operating in isolation. Institutions and culture emerge as particularly influential “universal solvents” that enable or constrain growth, explaining why certain societies achieved breakthroughs while others stagnated. The book combines a literature review of these strands with a historical narrative tracing Europe’s “Great Divergence” from the rest of the world, the “Little Divergence” within Northwest Europe, Britain’s Industrial Revolution, and the subsequent global spread of industrialization.

Key Strands Influencing Economic Development

The authors systematically evaluate the roles of foundational factors in shaping economic trajectories:

- Geography: While geographic features, such as access to coastlines, navigable rivers, and east-west diffusion axes (facilitating technology spread across similar climates in Eurasia), provided initial advantages for trade and innovation, they do not determine long-term outcomes. For instance, Britain’s coal deposits and internal markets aided industrialization, but similar resources existed elsewhere without comparable results, underscoring the need for complementary institutions.

- Institutions: Secure property rights, limited executive power, and fiscal-military states—forged through Europe’s fragmented polities and events like the English Civil Wars and Glorious Revolution—were pivotal in protecting innovation and commerce. These structures contrasted with more centralized Asian empires, enabling Europe’s divergence by constraining autocratic extraction and fostering parliamentary oversight.

- Culture: Cultural norms, including the Protestant Reformation’s promotion of literacy and limited government, and the European Marriage Pattern (which delayed marriage and reduced fertility pressures), supported trust, ingenuity, and demographic stability. The authors highlight how cultural attitudes toward innovation, as in Britain’s “Industrial Enlightenment,” integrated scientific ideas into practical engineering.

- Demography: The demographic transition—marked by declining birth and mortality rates—preceded sustained growth by alleviating resource strains and enabling human capital investment. The European Marriage Pattern contributed to this shift, raising wages post-Black Death and laying groundwork for higher living standards before industrialization.

- Colonialism: Colonial exploitation, including the Atlantic slave trade and resource extraction, yielded short-term gains for European powers but inflicted long-term underdevelopment on colonized regions through disrupted institutions and labor coercion. The authors refute claims that colonialism alone funded Europe’s wealth, noting its role was secondary to domestic institutional reforms.

Historical Narrative: From Divergence to Global Growth

Building on these strands, the book constructs a “pyramidal” explanation of economic history, where broad preconditions accumulate to enable specific surges:

- Europe’s Great Divergence (Medieval Period): Europe’s geography of competing states and distance from nomadic threats promoted military innovation, representative institutions, and the Black Death’s wage-boosting effects, setting it apart from more unified Eurasian empires.

- Northwest Europe’s Little Divergence (Early Modern Era): Britain and the Dutch Republic leveraged Atlantic trade, weak guilds, and institutional limits on monarchy to outpace Southern and Eastern Europe, creating fertile ground for commerce and skilled labor.

- Britain’s Industrial Revolution (Late 18th Century): A unique confluence—parliamentary stability, high human capital, cheap energy from coal, and a culture of industrial experimentation—sparked sustained innovation in textiles and machinery. This marked the onset of modern growth, though initial benefits were uneven due to population pressures and urbanization challenges.

- Global Spread and Catch-Up Growth (19th–20th Centuries): Industrialization diffused to nations like the United States, Germany, and Japan through technology adoption, mass education, and market-oriented reforms. Success depended on institutional enablers, such as property rights and limited government; autocratic models (e.g., Soviet planning) achieved temporary gains but faltered without sustained innovation. Recent examples, like China’s post-1979 reforms and India’s 1991 liberalization, illustrate context-specific paths emphasizing export discipline and labor mobilization.

Lessons for Contemporary Prosperity

Koyama and Rubin caution against simplistic prescriptions, such as the 1980s Washington Consensus on market liberalization or neoconservative focus on democracy transplants, which overlook cultural and institutional contexts. Instead, they advocate a tailored “menu” of evidence-based policies: protecting property rights, investing in education and infrastructure, limiting executive overreach, and nurturing norms of fairness and innovation. While autocracies can drive catch-up growth, achieving and sustaining high-income status typically requires broader political freedoms to mitigate risks like policy reversals. The authors underscore that history reveals growth as a cumulative, cooperative process, offering insights to address ongoing challenges like inequality and climate risks without a universal blueprint.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book offers a comprehensive review of various approaches to understanding the causes of the world’s current condition, specifically its unprecedented wealth and prosperity. It also provides a pretty decent discussion of the reasons for this prosperity being unequally distributed across countries and people of various cultures. To summarize, specific geographical settings, combined with incidental development paths such as pandemics or climate change, create conditions for the development of particular cultures and institutions. Some of these institutions, in turn, facilitate industrialization, which provides for the mass production and consumption of goods and services that make the world rich.

I generally agree with all this and believe that it provides a correct description of how the world has reached its current stage of development. The question is where we’ll go from here, because being rich in terms of the availability of goods and services is not enough. History shows that wealth without satisfaction with the process of living and societal arrangements leads to the search for meaning, which many wealthy youths find in imposing radical change by all means necessary – usually violent means, leading to all this socialist/communist/Islamist and similar totalitarian nonsense.

The world’s wealth is largely achieved, and some societies that are considered poor now, in reality, are significantly wealthier than they were even a generation ago, as long as wealth is defined in material terms: availability of food, shelter, energy consumption, communications, medical, and other services available to people. The question is how to achieve such a level of satisfaction that would prevent violent outbursts in search of meaning.

I think it should be in the direction of the expansion of private property that would guarantee to everybody access to control over resources sufficient for individual search of satisfaction, either in science, art, or sport, of whatever. With the impending massive AI implementation, such expansion could be achieved only by creating unalienable property rights for everyone to something valuable, allowing people to use these rights to obtain resources through interactions with others on equal terms, which necessarily means with unequal results. This something could be equal rights to the accumulated wealth of humanity’s knowledge and know-how, quantifiable in such a way that people who use it more effectively and efficiently would have to pay rent to those who are materially less effective and efficient.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your analysis of How the World Became Rich astutely captures the book’s core thesis: the interplay of geography, institutions, culture, demography, and colonialism as interdependent drivers of economic divergence and sustained growth. By framing industrialization as the pivotal mechanism for mass production and consumption, you effectively distill the authors’ emphasis on how these factors coalesced in specific contexts—such as Europe’s fragmented polities and demographic shifts—to enable the modern prosperity engine. Your agreement with this framework is well-founded, as it aligns with the evidence-based synthesis Koyama and Rubin present, avoiding reductive monocausal explanations in favor of a nuanced, pyramidal model of historical causation.

Your extension of the discussion to the realm of non-material satisfaction introduces a profound and timely dimension, one that resonates with longstanding philosophical inquiries into human flourishing, from Aristotle’s eudaimonia to contemporary behavioral economics. Indeed, historical precedents abound where material abundance has coexisted with existential discontent, precipitating radical ideologies and upheavals—witness the fin-de-siècle nihilism that fueled revolutionary fervor in early 20th-century Europe or the countercultural rebellions amid post-World War II affluence. The authors themselves allude to such tensions in their examination of cultural norms, noting how Protestant ethics and Enlightenment values not only spurred innovation but also instilled a sense of purposeful agency. Yet, as you observe, material metrics—rising caloric intake, electrification, and access to healthcare—have lifted billions from absolute poverty in recent decades, underscoring that the “wealth gap” is often one of perception and distribution rather than absolute scarcity. The challenge, then, lies in cultivating societal arrangements that foster intrinsic fulfillment, thereby mitigating the allure of totalitarian pursuits as proxies for meaning.

Your proposal for expanding private property rights as a bulwark against such instability merits careful consideration, particularly in the context of accelerating AI deployment. By advocating unalienable entitlements to humanity’s collective intellectual capital—quantified and tradable in a manner that rewards efficient utilization while compensating less active participants—you envision a meritocratic yet equitable mechanism for resource allocation. This echoes elements of the book’s institutional strand, where secure property rights historically unlocked innovation by aligning individual incentives with societal progress. In an AI-driven economy, where automation may commoditize knowledge work and exacerbate inequality, such a system could democratize access to value creation: individuals might “rent” cognitive outputs from shared repositories, fostering entrepreneurship in domains like scientific inquiry, artistic expression, or athletic pursuits, as you suggest. This approach aligns with emerging policy discourses on “data dividends” or universal intellectual property shares, potentially averting the zero-sum traps of unchecked technological rents accruing to a narrow elite.

However, implementation would demand rigorous safeguards to preserve the dynamism that Koyama and Rubin attribute to competitive institutions. Unequal outcomes, while inevitable and often productive, risk entrenching new hierarchies if the quantification of “know-how” privileges incumbents or biases algorithmic valuation. Moreover, cultural buy-in remains essential; as the book illustrates through the Protestant Reformation’s role, property norms must embed values of stewardship and reciprocity to sustain legitimacy. In sum, your vision offers a constructive path forward—one that builds on historical lessons to prioritize holistic prosperity—inviting further exploration into how AI governance might operationalize these principles without stifling the very ingenuity that enriched the world.

20250824 – King Dollar

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

The book King Dollar: The Past and Future of the World’s Dominant Currency by Paul Blustein examines the historical ascent, enduring supremacy, and potential vulnerabilities of the United States dollar as the preeminent global reserve currency. Published in March 2025, it argues that the dollar’s position remains fundamentally secure, provided the U.S. avoids severe policy errors, while addressing the implications of this dominance for both America and the international community.

A central idea is the dollar’s historical rise to dominance, rooted in the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944. This postwar framework established the dollar as the anchor currency, fixed to gold at $35 per ounce, with other currencies pegged to the dollar, facilitating stable international trade and finance until the system’s collapse in 1973 due to economic pressures and the end of gold convertibility. Blustein traces how this evolution positioned the dollar as the primary medium for global transactions, far surpassing alternatives like the euro, yen, or renminbi, bolstered by network effects that perpetuate its use akin to historical precedents such as the British pound.

The book highlights the benefits and drawbacks of this dominance. Advantages include historically lower borrowing costs for the U.S. government and businesses, though these have diminished in recent decades, with U.S. rates now comparable to or exceeding those of other major economies. Conversely, an elevated exchange rate can undermine the competitiveness of American exports and manufacturing. Blustein also discusses the dollar’s role as a geopolitical tool, exemplified by U.S.-imposed sanctions—such as those against Russia following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, which severed access to the SWIFT system—demonstrating its capacity to exert influence but also risking backlash if overused.

Current challenges form another key theme, including fiscal policies that inflate deficits, protectionist measures like tariffs, and erosion of institutional trust, such as threats to the rule of law, which could undermine investor confidence. Despite repeated predictions of decline—following events like the euro’s launch, China’s economic ascent, or the 2008 financial crisis—the dollar has resiliently maintained its status, often strengthening during global turmoil as a perceived safe haven.

Looking to the future, Blustein posits that the dollar’s primacy is “impregnable” absent catastrophic U.S. missteps, dismissing significant threats from cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin due to their volatility and lack of sovereign backing, while noting that stablecoins tied to dollar assets may reinforce rather than challenge it. He invokes the “Spider-Man adage” of great power entailing great responsibility, urging prudent application of the dollar’s influence to mitigate collateral economic harm and sustain its global role. Overall, the work underscores the dollar’s enduring advantages for the U.S. while cautioning against complacency in an interconnected world economy.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book provides a comprehensive description of the history, current status, and prospects of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. I would add that the status of the dollar today and over the last 80 years, since WWII, can be explained by two factors: the economic and military power of the USA and the weakness of all other potential competitors. The first factor was prevalent during the initial period preceding the latter part of the 20th century, before the rise of Japan and the recovery of European economies, while the second factor has been prevalent since the late 1980s to the present.

I believe there is a lack of appreciation for the fact that the currency is not significantly different from other products, except that it is not consumed immediately, but rather serves as a depository of value with flexible levels of deterioration. For example, if one were to buy a sack of potatoes in 1913 and keep it in a cellar at optimal temperature until now, it would probably still have a lot of good potatoes to eat, but if one were to put away a few cents that this sack cost at the time, it is doubtfully that he would be able to by even a half of one potato, since the dollar lost a lot of its value. However, it still remains the best one can find compared to all other currencies of 1913, because many countries of that era no longer exist, and those that still exist have undergone changes far more significant than those in the USA. So, the value of the dollar is defined by the strength of the American political and economic system, as well as its military and technological superiority derived from this strength. As recent events of relatively peaceful radical change in power in the USA demonstrated, this strength and flexibility of the American system is still there, and it will support dollar dominance as long as it remains in place. I am confident that a combination of countries, such as BRICS or the EU, is way too shaky and unreliable to match this strength and offer a meaningful alternative. Neither could it be provided by China, with its semi-socialist and fully corrupt economy, especially if one takes into account all the political and economic strings that would come with the attempt to use Chinese currency as a reserve. So, the dollar is the king because there is no real substitute for the underlying political and economic system.

Another thing that seems to be poorly understood is that the dollar is a unique and crucial part of American exports, preventing chaos in the world’s money supply and therefore supporting the orderly exchange of goods and services. Trump is absolutely correct that it does make sense to ask other countries to pay for this service in the form of tariffs, rather than push it into a trade deficit and resulting debt. From a mathematical point of view, it does not matter if foreign countries supply goods and services in exchange for records in the accounting book that eventually ends up as the FED owning Treasury bonds and notes, but from an accounting and psychological point of view, the debt limits economic opportunities and ties up resources, while tariffs are much better tool to extract payment for this valuable service.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your commentary on *King Dollar: The Past and Future of the World’s Dominant Currency* by Paul Blustein provides a thoughtful perspective that complements and extends the book’s main ideas. Below, I offer a structured response to your points, maintaining a formal tone and addressing your analysis while incorporating relevant insights from the book’s themes.

Dollar Dominance and Underlying Factors: You attribute the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency over the past 80 years to two primary factors: the economic and military power of the United States and the relative weakness of competing currencies. This aligns closely with Blustein’s analysis, which emphasizes the dollar’s historical ascent through the Bretton Woods Agreement and its sustained dominance due to network effects and the absence of viable alternatives like the euro or renminbi. Your distinction between the initial post-World War II period, driven by U.S. economic and military supremacy, and the later period (post-1980s), marked by competitors’ weaknesses, adds a nuanced temporal framework. Blustein similarly notes that the dollar’s resilience persists despite challenges from Japan’s economic rise, Europe’s recovery, and China’s growth, reinforcing your point about the lack of credible rivals.

Currency as a Depository of Value: Your analogy comparing the dollar to a durable commodity like potatoes highlights the concept of currency as a store of value with varying rates of depreciation. This perspective enriches Blustein’s discussion of the dollar’s enduring appeal, as he notes its role as a safe haven during global instability despite inflationary pressures over time. Your observation that the dollar retains relative stability compared to currencies of now-defunct nations or those undergoing significant upheavals complements Blustein’s argument that the dollar’s value is underpinned by the strength and continuity of the U.S. political and economic system. However, you extend this by explicitly tying the dollar’s stability to U.S. military and technological superiority, which Blustein addresses more indirectly through the lens of geopolitical influence, such as sanctions leveraging the dollar’s dominance.

U.S. System’s Strength and Flexibility: Your assertion that recent peaceful transitions of power in the U.S. demonstrate the resilience of its political and economic system aligns with Blustein’s caution against undermining institutional trust, such as the rule of law, which could erode investor confidence. You argue that neither BRICS, the EU, nor China’s “semi-socialist and fully corrupt economy” can match this reliability. Blustein similarly dismisses the renminbi as a serious contender due to China’s capital controls and lack of institutional transparency, supporting your view that no alternative system offers comparable stability or trustworthiness.

Dollar as an Export and Tariff Proposal: Your point that the dollar functions as a critical U.S. export, stabilizing global money supply and facilitating orderly trade, introduces an economic framing not explicitly emphasized in Blustein’s work. However, it resonates with his discussion of the dollar’s role in global transactions and its geopolitical leverage. Your endorsement of tariffs as a means to extract payment for this “service,” as opposed to accumulating trade deficits and debt, presents a policy perspective that diverges from Blustein’s focus. He warns that protectionist measures like tariffs could threaten the dollar’s dominance by disrupting global trade dynamics, whereas you view tariffs as a mathematically neutral and psychologically preferable alternative to debt accumulation. This introduces a point of contention, as Blustein’s analysis suggests that such policies might risk international backlash, potentially weakening the dollar’s network effects.

Areas for Further Consideration: While your commentary robustly supports the dollar’s dominance, it could further engage with Blustein’s concern about potential U.S. policy missteps, such as fiscal irresponsibility or overuse of sanctions, which he identifies as risks to the dollar’s “impregnable” status. Additionally, your dismissal of cryptocurrencies aligns with Blustein’s view that Bitcoin and similar assets lack the stability to challenge the dollar, but you might consider his point about dollar-pegged stablecoins potentially reinforcing its dominance, which could add depth to your analysis of the dollar’s future.

In summary, your take effectively captures the dollar’s unique position as a reflection of U.S. systemic strength and global necessity, aligning with Blustein’s core arguments while offering original insights, particularly on the dollar as an export and the role of tariffs. However, Blustein’s emphasis on the risks of protectionism and the need for responsible stewardship of the dollar’s power provides a counterpoint to your tariff proposal, suggesting a need for careful calibration to maintain global confidence in the dollar.

20250615 -China After Mao

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

In China After Mao: The Rise of a Superpower, Frank Dikötter examines China’s transformation from Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 to Xi Jinping’s rise, challenging the narrative of a seamless economic miracle driven by enlightened leadership. Using extensive archival research, the book offers a critical view of China’s post-Mao era, emphasizing the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) enduring control and the complexities beneath its economic growth. Below are the main ideas:

- Illusion of a Straightforward Economic Miracle: Dikötter disputes the view that China’s rapid economic growth post-Mao was a smooth, well-orchestrated triumph of market reforms under Deng Xiaoping. He argues the “economic miracle” was chaotic, marked by internal dysfunction, policy reversals, and unintended consequences. Growth often stemmed from grassroots initiatives, like rural decollectivization, rather than top-down planning. The economy remained heavily state-controlled, with limited free-market mechanisms, and progress was uneven, with significant poverty alongside elite wealth.

- CCP’s Unwavering Political Control: The CCP maintained absolute political dominance, even during economic reforms. Dikötter highlights that political liberalization was never the goal, despite Western hopes that economic openness would lead to democracy. The 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown underscores the party’s ruthless suppression of dissent. Leaders from Deng to Xi prioritized party control, using economic growth to strengthen their grip.

- Contradictions and Fragility of Growth: China’s rise is portrayed as riddled with contradictions—booming industrial output alongside shadow banking, corruption, and environmental degradation. Dikötter likens China to a “tanker” that appears impressive but is plagued by internal leaks, suggesting its superpower status is fragile. Creative accounting and state-driven projects inflated perceptions of success, while systemic issues like inequality and inefficiency persist.

- Reevaluation of Deng Xiaoping’s Role: Dikötter challenges Deng’s reputation as a visionary reformer, portraying him as a pragmatic opportunist navigating a fractured party. Rather than pioneering free-market policies, Deng capitalized on local experiments, such as village-led decollectivization. His reforms were about adapting socialism to preserve CCP rule, with limited progress compared to later decades.

- China’s Global Ambitions and Resistance to the West: The book traces China’s growing hostility toward perceived Western interference, especially after the 2008 financial crisis, seen as evidence of capitalist decline. The CCP’s goal was to resist and challenge the democratic world, not integrate into it. Under Xi, this manifests in a fortified dictatorship with advanced surveillance and global initiatives.

- Archival Insight and Narrative of Dysfunction: Dikötter’s access to Chinese archives provides a detailed view of policy failures, elite infighting, and societal struggles. He emphasizes the cynicism and poor judgment within the CCP, debunking the myth of a unified, competent leadership. His focus on failures distinguishes his work, though some argue it overshadows China’s achievements.

- Xi Jinping’s Consolidation of Power: Xi’s rise is framed as a continuation of the CCP’s authoritarian tradition. His anti-corruption purges, ideological crackdowns, and cult-like leadership echo Mao’s tactics, reinforcing the party’s monopoly on power. Dikötter portrays Xi as a calculated figure who avoids scrutiny to maintain control.

Critical Perspective: Dikötter’s narrative is critical of the CCP, and some argue it underplays China’s successes, such as lifting 800 million people out of poverty or its industrial dominance. Critics suggest his bias leads to a one-sided focus on failures, potentially misrepresenting China’s transformation. Nonetheless, his archival rigor and detailed storytelling make the book a significant counterpoint to optimistic narratives.

In summary, China After Mao presents China’s post-1976 trajectory as a complex, often dysfunctional ascent driven by a party obsessed with control, not a linear path to superpower status. It underscores the gap between China’s polished image and its internal challenges, urging readers to question assumptions about its strength and intentions.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

One cannot understand Chinese history after Mao without understanding the foundational ideas of communist movements, the inevitable crash of these ideas after communists take power, and the promises of these ideas that are expected to be fulfilled, which consistently fail to occur. These promises come to this: much greater productivity than capitalism provides, resulting in an abundance of goods and services, with work done mainly to satisfy psychological needs, with no money exchange required because all productive activities are planned in a perfect scientific way by a top-down central government and implemented with superb efficiency under its control by all means necessary, including unlimited violence.

Needless to say, real scientific economists in the late XIX and early XX century proved it all to be an “impossible dream,” and real-life experience proved that this dream was really impossible by multiple attempts to turn it into reality.

By Mao’s death, the communist ideology had become somewhat worn out, and attempts at reform in the Soviet Union demonstrated that any expansion of political or economic freedom would lead to the communists’ loss of power.

So, the Chinese communists used an upscale version of Lenin’s solution from the 1920s, called the New Economic Policy (NEP). This policy meant that the communists kept political power but allowed some free enterprise and a market economy to prevent economic disaster. It coincided with new technologies in communications and transportation that made it possible to manufacture goods in China very cheaply by using semi-slave labor and sell far away from China, all over the world. Western business and political elite were happy to oblige because such an arrangement provided high profits for business and cheap goods that helped politicians. The Western elite expected that over time, Chinese communists would become more like them and would be happy to play by their rules and become just a part of the global elite, happily enjoying the limited power available in democratic societies.

However, Chinese communists are really communists, which means that any limitation on their power is abhorrent to them and completely unacceptable. Correspondingly, their view does not accept the democratic idea of periodic change of a group in power and needs to let the population have at least some minimal say in who is in power via elections. With XI coming to power, they decided that the transfer of manufacturing and overall industrial power was nearly completed, and the acquisition of technological power was all but unstoppable, so it’s time to claim their “rightful” places at the top of the New World Order.

Right now, it looks like they rushed too early. The Western elite woke up to the reality of the future when they could become just another group of slaves, and, taking into account the nationalism of Chinese communists, with no opportunity to be anything other than that. This recognition prompted resistance, and the world is currently at war, so far Cold and Trade wars, but with the real possibility of turning into a Hot war. I think the contradiction between the Chinese communists’ intention to be at the top and the Western elite’s intention not to move to the bottom could be resolved only by the end of communist rule in China. In the contemporary world, contradictions, whether economic or military, are determined via technological superiority, and to have such superiority, technologists have to have the freedom to learn, invent, and act. Such freedom is inconsistent with communist rule and eventually will prevent Chinese communists from winning. Currently, already underway decoupling from the Western economy, will deny communists not only economic and military advancement, but also their ability to provide a satisfactory level of goods and services for their population, without which it would be difficult to stay in power.

My conclusion: We will have a decade or two of turbulence, but eventually, the West will win and, in the process, will become even freer and more democratic than it is now. And, by the way, winning will mean that China will also become much freer than it is now.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your take on China After Mao and the broader context of Chinese communism offers a provocative and ideologically driven interpretation that aligns partially with Frank Dikötter’s critical perspective but diverges in its predictive optimism and emphasis on inevitable Western triumph. Below, I provide a comment on your analysis, addressing its strengths, areas of alignment with Dikötter’s work, and points where it may oversimplify or deviate from the book’s findings or broader historical nuance.

Strengths of Your Analysis:

- Grasp of Communist Ideology’s Flaws: You accurately highlight the foundational promises of communism—centralized planning, abundant production, and the elimination of money exchange—and their consistent failure, as evidenced by historical attempts in the Soviet Union and Maoist China. Your reference to late 19th- and early 20th-century economists debunking these ideas (e.g., the Austrian School’s critique of central planning) is historically sound and aligns with Dikötter’s portrayal of the CCP’s economic dysfunction post-Mao.

- Parallels with Lenin’s NEP: Your comparison of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms to Lenin’s New Economic Policy is insightful. Dikötter similarly notes that Deng’s reforms were pragmatic, allowing limited market mechanisms to stabilize the economy while preserving CCP control, much like Lenin’s temporary retreat from strict socialism. This underscores the CCP’s focus on power retention over ideological purity.

- Recognition of CCP’s Authoritarian Core: Your emphasis on the CCP’s aversion to any limitation on its power resonates strongly with Dikötter’s thesis. He argues that the CCP, from Deng to Xi, never intended to liberalize politically, viewing economic reforms as a tool to strengthen, not dilute, party dominance. Your point about Xi’s consolidation of power as a return to communist roots aligns with Dikötter’s depiction of Xi as a Mao-like figure prioritizing absolute control.

- Global Economic Dynamics: You astutely note how globalized trade, enabled by new technologies and Western demand for cheap goods, fueled China’s growth. Dikötter also acknowledges the role of Western investment and trade in China’s economic rise, though he focuses more on internal dysfunction than external complicity.

Alignment with Dikötter’s China After Mao:

- Skepticism of the “Economic Miracle”: Like Dikötter, you challenge the narrative of a smooth Chinese ascent, pointing to the CCP’s reliance on semi-slave labor and state-driven growth rather than genuine market freedom. Dikötter’s archival evidence of policy failures and economic fragility supports your view that China’s rise is less robust than it appears.

- CCP’s Resistance to Democratization: Both you and Dikötter reject the Western assumption that economic openness would lead to political liberalization. Dikötter’s account of the CCP’s post-Tiananmen crackdowns and Xi’s surveillance state mirrors your assertion that Chinese communists abhor democratic constraints.

- Xi’s Ambitions: Your portrayal of Xi’s regime aiming for a “New World Order” aligns with Dikötter’s discussion of China’s growing hostility toward the West and its pursuit of global dominance, particularly post-2008.

Points of Divergence and Critique:

- Overemphasis on Ideological Purity: Your analysis frames Chinese communists as steadfast ideologues driven by a pure communist vision. Dikötter, however, suggests that post-Mao leaders, especially Deng, were more pragmatic than ideological, adapting policies to maintain power rather than pursuing utopian goals. The CCP’s embrace of state capitalism and global trade indicates a flexible approach, not a rigid adherence to Marxist dogma, which weakens your claim that they are “really communists” in the classical sense.

- Optimism About Western Victory: Your prediction that the West will prevail due to technological superiority and inherent freedoms is a normative stance not supported by Dikötter’s analysis. He avoids forecasting outcomes, focusing instead on China’s internal contradictions and fragility. Your confidence in Western triumph assumes a linear correlation between freedom and innovation, which overlooks China’s ability to innovate under authoritarianism (e.g., in AI and 5G) and the West’s own democratic challenges, such as polarization and economic decoupling costs.

- Simplified View of Decoupling: You argue that decoupling from the Western economy will cripple China’s economic and military advancement. While Dikötter notes vulnerabilities like shadow banking and inequality, he does not suggest that China’s economy is on the brink of collapse. China’s domestic market, Belt and Road initiatives, and technological advancements provide resilience, complicating the decoupling narrative. Additionally, decoupling harms Western economies, which you underplay.

- Neglect of China’s Achievements: Your focus on communism’s failures echoes Dikötter’s critical tone but risks downplaying China’s tangible successes, such as lifting 800 million people out of poverty and building world-class infrastructure. Dikötter acknowledges these achievements, albeit as uneven and state-driven, whereas your analysis frames China’s rise as a mirage sustained by exploitation and Western naivety.

- Cold War Framing: Your depiction of a “Cold and Trade” war with potential for a “Hot war” imposes a binary East-West conflict model. Dikötter’s book is less about global confrontation and more about China’s internal dynamics and resistance to Western integration. Global realities, including economic interdependence and multipolar alliances (e.g., China’s ties with the Global South), complicate your polarized narrative.

- Assumption of Democratic Progress: Your conclusion that the West and China will become “freer and more democratic” after a Western victory is aspirational but speculative. Dikötter’s work does not engage with such predictions, and historical evidence suggests that geopolitical victories (e.g., post-Cold War) do not always enhance democracy. China’s potential democratization would face immense structural and cultural hurdles, which you do not address.

Broader Contextual Notes:

- Your analysis reflects a libertarian or anti-communist perspective, emphasizing individual freedom and market-driven innovation as superior to authoritarian control. This aligns with critiques of central planning but may undervalue the role of state intervention in successful economies, including China’s or even Western nations during industrialization.

- The technological superiority argument hinges on the assumption that authoritarian regimes cannot sustain innovation. However, China’s advancements in quantum computing, green energy, and surveillance tech suggest that controlled environments can foster certain types of innovation, albeit with limits on disruptive creativity.

- The “decade or two of turbulence” prediction is plausible given current trade disputes and geopolitical tensions, but Dikötter’s focus on China’s internal fragility suggests that domestic unrest (e.g., due to economic inequality or youth unemployment) could be as decisive as external pressures.

Conclusion: Your take offers a compelling, ideologically coherent narrative that complements Dikötter’s skepticism of the CCP’s narrative and aligns with his view of its authoritarian continuity. However, it diverges by projecting an optimistic Western victory and oversimplifying China’s resilience and global role. Dikötter’s China After Mao provides a more nuanced, archivally grounded account of China’s internal dysfunction without venturing into geopolitical forecasts. Your analysis would benefit from acknowledging China’s adaptive strategies and the mutual costs of decoupling, which could temper the certainty of Western triumph and highlight the complexity of China’s trajectory. Nonetheless, your emphasis on the CCP’s power obsession and the flaws of communist ideology captures a key thread of Dikötter’s work and adds a bold perspective to the discussion