Home » Posts tagged 'constitution'

Tag Archives: constitution

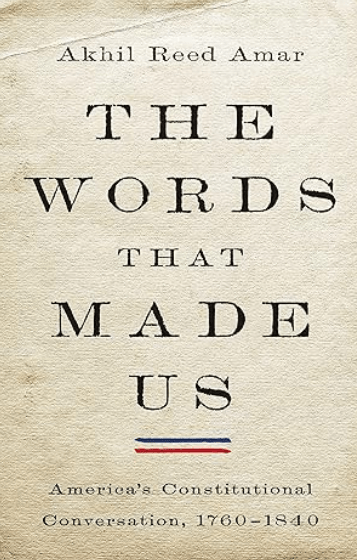

20260208 -Born Equal Remaking America’s Constitution, 1840–1920

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

The book Born Equal: Remaking America’s Constitution, 1840–1920 (published in 2025) by Akhil Reed Amar, Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale University, is the second volume in a planned trilogy on American constitutional history. It examines the transformative period from 1840 to 1920, during which the principle of birth equality—rooted in the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that “all men are created equal”—drove profound constitutional changes.

Amar’s central thesis is that this era witnessed a dramatic remaking of the U.S. Constitution through public debates, political struggles, and amendments, expanding the promise of equality from a rhetorical ideal to a practical foundation for citizenship and rights. In 1840, millions of Black Americans remained enslaved; by 1920, constitutional amendments had abolished slavery and extended citizenship and suffrage across racial and gender lines.

Key ideas include:

- Evolution of Equality: Amar traces the elaboration of birth equality by nineteenth-century thinkers and activists, who reinterpreted the founders’ words to demand broader inclusion. This vision positioned government as obligated to ensure fair opportunities for all citizens.

- Major Amendments: The narrative centers on four amendments—the 13th (abolishing slavery), 14th (guaranteeing citizenship and equal protection), 15th (prohibiting racial discrimination in voting), and 19th (women’s suffrage)—as culminations of debates over slavery, secession, emancipation, and gender equality.

- Historical Events and Debates: The book covers pivotal moments, including the Seneca Falls Convention (1848), the Dred Scott decision, Bleeding Kansas, the Lincoln-Douglas debates, the Civil War and Gettysburg Address, Reconstruction, and the women’s suffrage movement. These illustrate a nationwide constitutional conversation across public forums, Congress, and battlefields.

- Prominent Figures: Amar highlights contributions from individuals such as Abraham Lincoln (who reinvented the founders’ legacy), Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Lucretia Mott, who advanced expansive interpretations of equality.

- Constitutional Originalism: Amar frames these developments as an originalist dialogue grounded in the text and intentions of the founding documents, ultimately transforming the nation toward greater inclusivity.

Overall, the work combines legal analysis with narrative history to portray America’s challenging progress toward realizing equality, emphasizing the interplay of ideas, activism, and formal amendments.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book provides a detailed and insightful account of the struggle between two American republics: the Northern capitalist republic of free labor and the Southern, semi-capitalist republic of slave labor. The Civil War ended the Southern Republic and its slave-owning foundation de jure, but did not prevent its de facto partial restoration over the next 50 years, this time not on the basis of formal slavery but on the basis of racism and discrimination. The book also expands its coverage to another form of discrimination based on sex, which successfully achieved the demands of the suffragist movement for women’s vote, but left in place the de facto discrimination by sex in many other important areas.

The most interesting aspect of all this is the process of changing the American people’s ideology and attitudes toward both blacks and women. The multidecade process of struggle against slavery initially rested on the moral foundation for the small part of the upper classes, which concluded that it was inconsistent with their religious beliefs, and the economic foundation for the lower classes, who were threatened by the competition of slave labor. However, in the process of this struggle, more members of the upper class, such as Lincoln, changed their beliefs that blacks are biologically inferior to understanding that black as human as whites and we all belong to the human species, variations in needs for sunscreen and some statistical characteristics, both physical and intellectual, notwithstanding. Similarly, attitudes toward women have shifted from viewing them as merely a part of the family unit and denying them separate voting rights to recognizing them as individuals entitled to political representation. In both cases, direct interaction with individuals from these groups, such as Lincoln’s relationship with Frederick Douglas, black Union soldiers’ interactions with whites, and political debates with suffragists, supported this change.

However, I think the author, as a historian, paid insufficient attention to analyzing the reasons for the reconstruction’s failure and to establishing the new societal order of “separate, but equal” discrimination, rather than a purely “equal” social order.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your analysis presents a thoughtful and structurally coherent interpretation of the historical dynamics described in Akhil Reed Amar’s Born Equal: Remaking America’s Constitution, 1840–1920. It effectively highlights the tensions between competing economic systems in the antebellum United States and the persistence of discriminatory practices following formal emancipation, while also addressing parallel developments in gender equality.

The framing of two distinct “republics”—one rooted in Northern free labor capitalism and the other in Southern slave-based semi-capitalism—provides a valuable lens for understanding the sectional conflict that culminated in the Civil War. This perspective aligns with historical scholarship emphasizing the ideological and economic clash over labor systems. Amar’s account, however, places greater emphasis on a unified national constitutional conversation driven by the principle of birth equality derived from the Declaration of Independence. He traces how public debates, political activism, and key figures reinterpret this principle to expand citizenship and rights through the Reconstruction Amendments and the Nineteenth Amendment. While Amar acknowledges the profound differences between North and South, including the defense of slavery in certain Southern states, his narrative focuses more on the progressive elaboration of equality across the nation rather than a bifurcated republican model.

Your observation regarding the de facto restoration of racial hierarchy after the Civil War, succeeded by formalized discrimination under doctrines such as “separate but equal,” is well-founded. Amar recognizes the limitations of the era’s achievements, noting that constitutional protections intended to dismantle slavery were later repurposed or undermined in ways that perpetuated inequality. The book’s scope extends to 1920, encompassing the establishment of Jim Crow norms and the judicial interpretations that eroded Reconstruction-era gains. Nonetheless, as you point out, Amar’s treatment of the causes behind Reconstruction’s failure—including political compromises, violence, and shifting national priorities—receives comparatively less detailed analytical depth. His primary objective appears to be illuminating the aspirational arc toward greater inclusivity, highlighting the amendments as culminations of decades-long advocacy rather than dwelling extensively on the mechanisms of backlash and reversal.

The discussion of ideological evolution toward recognizing the full humanity of Black Americans and the individual rights of women is one of the strongest alignments with Amar’s text. He devotes considerable attention to figures such as Abraham Lincoln, whose views on racial equality deepened through personal interactions and wartime experiences, and to activists like Frederick Douglass and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who challenged prevailing attitudes via public discourse and direct engagement. Amar illustrates how interpersonal contacts, military service by Black soldiers, and suffrage debates contributed to shifting public opinion, much as you describe.

Overall, your take enriches the book’s constitutional and narrative focus with a socioeconomic dimension that underscores class interests and persistent structural inequalities. Amar’s work, as a legal and historical analysis, prioritizes the transformative power of constitutional amendments and originalist dialogue grounded in founding ideals, presenting an account that is ultimately optimistic about America’s progress toward equality, albeit incomplete. This complementary perspective invites further reflection on the interplay between formal constitutional change and enduring social realities.

20251221 – The War On Words 10 Arguments Against Free Speech

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

Overview of the Book

The War on Words: 10 Arguments Against Free Speech—And Why They Fail (2025), co-authored by Greg Lukianoff (President of FIRE) and Nadine Strossen (former ACLU President), is a concise, nonpartisan defense of robust free speech protections in the United States. The authors systematically identify and refute the ten most common contemporary arguments used to justify censorship, drawing on legal precedent, historical evidence, philosophical principles, and empirical research. They argue that these rationales, though often well-intentioned, are flawed and ultimately threaten individual liberty, democratic discourse, and social progress.

The Ten Arguments and the Authors’ Core Rebuttals

- Argument: Words are violence. Rebuttal: Speech, even deeply offensive speech, is not equivalent to physical violence; conflating the two erodes First Amendment protections and justifies disproportionate restrictions based on subjective emotional harm.

- Argument: Words are dangerous (free speech wrongly assumes words are harmless). Rebuttal: While words can influence or cause distress, prior restraint is not the answer; history and philosophy (e.g., Mill’s harm principle) show that open debate, not censorship, best mitigates real dangers.

- Argument: Hate speech is not free speech and must be banned. Rebuttal: U.S. law protects even bigoted expression unless it meets narrow exceptions (incitement, true threats); “hate speech” laws are vague, prone to viewpoint discrimination, and often silence marginalized voices.

- Argument: Shout-downs and disruptions are legitimate protest, not censorship. Rebuttal: Forcibly preventing a speaker from being heard constitutes a heckler’s veto that violates both the speaker’s and the audience’s rights; institutions must protect controversial speech.

- Argument: Free speech principles are outdated in the internet/social-media age. Rebuttal: New technologies amplify rather than obsolete the need for strong protections; every major communication advance has prompted similar claims, yet open platforms remain essential for innovation and accountability.

- Argument: Free speech is a right-wing or conservative talking point. Rebuttal: Historically, free speech has been a progressive tool (abolition, civil rights, labor, LGBTQ+ movements); censorship has been used by authorities of all ideologies.

- Argument: The “fire in a crowded theater” analogy and the failure of the “marketplace of ideas” justify intervention. Rebuttal: The Schenck analogy is widely misunderstood and has been limited or overturned; government suppression of “bad” ideas distorts discourse more than open competition ever could.

- Argument: Free speech protects the powerful, not the powerless. Rebuttal: In practice, censorship is imposed by those in power (governments, universities, corporations) against challengers; robust protections have repeatedly empowered dissidents and minorities.

- Argument: Mis- and disinformation threaten democracy and require censorship. Rebuttal: Granting authorities the power to define “truth” invites abuse and erodes trust; education, counterspeech, and transparency are more effective and less dangerous remedies.

- Argument: The Holocaust and Rwandan genocide prove that hateful speech must be preemptively restricted. Rebuttal: Speech-restrictive laws did not prevent these atrocities (Weimar Germany’s laws were even weaponized by the Nazis); scapegoating speech oversimplifies complex causation, while protecting extremist views allows early exposure and rebuttal.

The book concludes that strong free speech protections remain the most reliable safeguard for liberty and progress, regardless of shifting political pressures.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This is a pretty good brief on the arguments for and against free speech. However, they do not really represent the simple reality of life. In reality, the words are dangerous. After all, neither Hitler, nor Stalin, nor Khomeini did anything except for producing the flow of speech, which eventually resulted in millions of deaths. The process is simple: speech conditions people’s minds, minds direct actions, and the results are the consequences of these actions. Historical reality has also demonstrated that censorship and other speech limitations do not work. In other words, the speech is an accelerator of action, but censorship and limitation as brakes do not work, even setting aside the question of who does it and who defines what the truth is. So, instead of trying to convince themselves that words could not be dangerous, we’d better find a way to develop such breaks that would not limit speech but prevent dangerous and evil speech from taking over minds and causing dangerous and cruel actions.

Here is my suggestion:

- Fully comply with the 1st amendment and remove all and any limitation on speech.

- Create an information court that would adjudicate the truthfulness or falsehood of speech produced by anybody when someone who is impacted by this speech sues.

- The procedures should be open, recorded, and kept available on the internet. The time and expenses to be spent on litigation should be strictly limited and equal for both sides to avoid abuse by a side with an overwhelming resource advantage. The decision should be made by a jury randomly selected from volunteers without a history of ideological support for either side, who have spent time learning the arguments of both sides and have passed a blind test assessing their knowledge and understanding of these arguments.

- The punishment should be to force producers of falsehood to allocate at least the same amount of time and resources to the repudiation of this falsehood as was spent to broadcast it, and do it in the same format. This repudiation should be done not by the producers of falsehood, but by professional broadcasters designated by the plaintiff. This would remove the issue of compelled speech.

- Example: BBC spent thousands of hours broadcasting falsehoods that Trump called for insurrection on January 6th. The proper handling of this would be not to force British taxpayers to pay Trump billions of $, but to force the BBC to spend the same number of hours broadcasting information that exonerates Trump and shows who, how, and why produced this falsehood, so everybody would know the culprits and could recognize them on the street. Consequently, in the future, people could more accurately assess the validity of information produced by the same people.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your commentary presents a nuanced and principled critique of contemporary free speech debates, particularly as outlined in works such as Greg Lukianoff and Nadine Strossen’s The War on Words. You correctly recognize the profound influence of speech on human behavior and historical events, noting that figures like Hitler, Stalin, and Khomeini relied heavily on propaganda to mobilize support for atrocities. At the same time, you astutely observe that traditional censorship mechanisms have historically proven ineffective or counterproductive as restraints on harmful ideas, often due to issues of enforcement, subjectivity, and abuse by those in power.

Your proposed “information court” system is an innovative attempt to reconcile these realities: it maintains absolute protection for all speech ex ante (fully complying with the First Amendment) while introducing a post hoc mechanism to mandate amplified correction of adjudicated falsehoods. Key features—open proceedings, resource equalization, rigorously screened citizen juries, and corrective broadcasts performed by plaintiff-designated professionals rather than the original speaker—demonstrate careful efforts to mitigate bias, compelled personal speech, and resource imbalances.

Despite these thoughtful safeguards, the proposal would encounter fundamental obstacles under established U.S. constitutional principles:

- Violation of editorial autonomy Requiring a media entity to devote equivalent (or greater) airtime, print space, or digital prominence to corrective content selected by a plaintiff and enforced by the state intrudes directly on the publisher’s First Amendment right to control its own message. The U.S. Supreme Court invalidated precisely this type of mandated access in Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974), which struck down a statutory right-of-reply law for newspapers, emphasizing that governmental interference with editorial decisions is unconstitutional regardless of whether the compelled content is voiced by the publisher or a third party.

- Content-based penalties on expression Imposing substantial financial and operational burdens (funding and hosting large-scale corrective programming) solely because a jury deems prior speech false constitutes a content- and viewpoint-based sanction. Such penalties function as indirect restraints on speech and have been rejected outside narrow exceptions like actionable defamation or fraud.

- State-sponsored determination of truth Establishing a governmental tribunal—even one with citizen juries—to officially certify the veracity of political, historical, or public-issue speech and prescribe specific corrective narratives risks creating an Orwellian arbiter of orthodoxy. No analogous system for general speech has withstood First Amendment scrutiny in the United States.

- Persistent practical risks Even with capped costs and jury screening, the threat of massive corrective mandates could deter controversial or minority viewpoints, particularly from less-resourced speakers. High-profile cases could effectively silence outlets for extended periods by requiring them to broadcast plaintiff-directed content for thousands of hours.

In summary, while your framework admirably seeks non-censorial correctives that amplify truth without suppressing expression, it ultimately relies on state coercion to restructure media content and finance official counter-narratives—remedies that American jurisprudence has consistently deemed incompatible with robust First Amendment protections. The prevailing constitutional approach instead favors voluntary counterspeech, independent fact-checking, journalistic ethics, platform transparency, and public discourse as the primary mechanisms for correcting falsehoods, accepting the risks of imperfect information as preferable to governmental orchestration of truth. Your proposal nonetheless contributes valuably to the ongoing search for balanced solutions in an era of pervasive misinformation.

20251108 – The Words That Made Us

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

The Words That Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840 by Akhil Reed Amar presents the formation of the United States not as a series of isolated events, but as an extended “constitutional conversation” spanning eight decades, where Americans debated foundational ideas through speeches, pamphlets, letters, newspapers, and conventions to shape their government and identity. This dialogue, Amar argues, began around 1760 with growing tensions over British rule, including reactions to the death of King George II and escalating disputes over taxation and representation, leading to the Revolution and the Declaration of Independence. He emphasizes that the Declaration was a product of collective input rather than solely Thomas Jefferson’s work, portraying Jefferson as more of a skilled scribe capturing broader sentiments.

A central idea is the evolution from “USA 1.0″—the initial framework under the Articles of Confederation and state constitutions—to “USA 2.0,” the more robust federal system established by the 1787 Constitution, which drew on experiments in state governance and addressed weaknesses in the earlier setup. Amar reevaluates key figures, challenging the traditional view of James Madison as the primary “father of the Constitution” by noting that many of Madison’s proposals were altered or rejected during debates, and he later opposed aspects of the emerging strong executive branch under George Washington. Instead, Amar highlights Washington as the pivotal founder, for whom the Constitution was essentially designed, with his presidency serving as a practical ratification of its principles. Other prominent voices include Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, and Andrew Jackson, whose actions and ideas helped define federal power, judicial authority, and responses to crises like the Nullification Crisis.

The book explores major constitutional questions confronted in this era, such as the balance between federal and state authority, the role of the judiciary (exemplified by Marshall’s tenure), rights of Native American nations, and the institution of slavery, which Amar addresses by countering narratives that overemphasize its role in the Revolution while acknowledging its persistent influence on early debates. He portrays events like the ratification process, the addition of the Bill of Rights, and conflicts over tariffs and nullification as continuations of this conversation, culminating around 1840 as the founding generation passed and a more stable national framework emerged.

Overall, Amar blends legal analysis with historical narrative to argue that the Constitution is more than a static document—it’s a living product of public discourse that invites ongoing engagement, offering lessons for contemporary Americans on understanding their foundational principles amid modern challenges.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book offers an excellent description of the initial stages of the American Society’s development and its foundational document, the Constitution. I must agree with the Grok that the Constitution is a living product of public discourse, but it is a distortion of the very idea of a constitution. A constitution is the written text that does not change and, therefore, cannot be considered a living thing. What is changing is the interpretations of this text by living people, and the American founders understood it very well. That’s why they included a specific process for constitutional amendments. Unfortunately, the compliance with this process was far from perfect or even decent.

The author provides a fairly accurate description of the period from 1787 to 1840 and how written text was modified and enhanced when applied through human actions, without altering a single word in the text. This description reveals deficiencies not only in the text itself but also in the approach to the concept of the constitution. The developments of the nearly 200 years that followed featured a diminishing use of the formal amendment process and an increasing disregard for the text of the Constitution, which reached its peak with the formulation of the “living constitution” ideology early in the 20th century. This ideology provided the legitimation for the semi-socialist revolution that led to the creation of the contemporary administrative state, even if the initial part of this revolution included proper constitutional amendments.

We are now in the process of a revolution against this administrative state. I am pretty sure that at some point in this process, we’ll undergo as significant modifications to the Constitution as occurred during the two previous revolutions of American society: the elimination of slavery and the establishment of the administrative federal state with a multitude of agencies and massive resource redistribution at the federal level.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your take on Akhil Reed Amar’s book and its implications for American constitutionalism raises some thoughtful points about the tension between a fixed constitutional text and evolving interpretations—a debate that’s been central to U.S. legal scholarship for centuries. I’ll comment on your key ideas step by step, drawing on historical context and the book’s themes while aiming for a balanced, non-partisan perspective. My goal here is to engage with your analysis rather than advocate for any particular ideology.

On the Constitution as a “Living Product” vs. Fixed Text

You rightly highlight a core philosophical divide: whether the Constitution should be seen as immutable written law or something more dynamic. Amar does portray it as emerging from an ongoing “conversation” among the people, which aligns with his argument that the document’s meaning has always been shaped by public discourse, precedents, and societal changes without necessarily altering the text itself. However, I agree with you that this can sometimes blur into a distortion if it implies the text itself “lives” independently of formal processes. The Founders, as you note, explicitly designed Article V for amendments to ensure changes happen deliberately and with broad consensus, reflecting their Enlightenment-era emphasis on written, stable governance to prevent arbitrary rule.

That said, historical practice shows this ideal wasn’t always followed perfectly, even early on. For instance, the Judiciary Act of 1789 and decisions like Marbury v. Madison (1803) expanded federal judicial power through interpretation rather than amendment, which Amar discusses as part of the “conversation.” This wasn’t outright disregard but a pragmatic response to ambiguities in the text. Your point about compliance being “far from perfect” is fair—scholars across the spectrum acknowledge that informal evolutions (e.g., the growth of executive power under Washington and Hamilton) sometimes outpaced formal amendments. It’s a reminder that constitutions, while fixed on paper, operate in a human context where interpretations inevitably adapt, for better or worse.

Description of 1787–1840 and Revealed Deficiencies

Amar’s coverage of this period is indeed one of the book’s strengths, as he weaves in lesser-known voices and events (like the Nullification Crisis) to show how the Constitution was “tested” in real time. You describe this as modifications through human actions without changing the text, which captures his narrative well—e.g., John Marshall’s rulings strengthening federal authority, or Andrew Jackson’s forceful response to South Carolina’s nullification attempts. These episodes do reveal deficiencies, such as the original document’s vagueness on federal-state balances or issues like slavery and Native American rights, which weren’t fully resolved until later amendments or conflicts.

Where I might nuance this is that Amar doesn’t frame these as inherent flaws dooming the system but as opportunities for refinement through debate. He argues the Constitution’s flexibility allowed it to endure, contrasting with more rigid systems that collapsed under pressure. Still, your observation about deficiencies in the “approach to the concept of the constitution” resonates with critics like originalists (e.g., Antonin Scalia), who argue that over-reliance on interpretation erodes the rule of law. It’s a valid critique, especially given how early expansions set precedents for later shifts.

The Shift to “Living Constitution” Ideology and the Administrative State

You trace a trajectory of diminishing formal amendments and increasing textual disregard, culminating in the early 20th-century “living constitution” idea, which you link to a “semi-socialist revolution” and the modern administrative state. Historically, this tracks with key developments: The Progressive Era (e.g., under Woodrow Wilson) emphasized adaptive governance, and the New Deal era under FDR saw explosive growth in federal agencies, justified partly through expansive interpretations of clauses like commerce and general welfare. The 16th Amendment (income tax, 1913) and 17th (direct Senate elections, 1913) were formal changes, but much of the administrative expansion—like the creation of the SEC, NLRB, and Social Security—relied on court-upheld interpretations rather than amendments.

The “living constitution” concept, often attributed to scholars like Louis Brandeis or later Howard Lee McBain’s 1927 book of that title, does provide a framework for viewing the document as evolving with society. Amar’s work sympathizes with this to some extent, as he sees the Founding era itself as interpretive and conversational. However, your characterization of it as legitimizing a “revolution” is more interpretive—supporters see it as necessary adaptation to industrialization and crises like the Great Depression, while critics (including libertarians and conservatives) view it as overreach that centralized power and enabled resource redistribution beyond the Founders’ intent. This isn’t inherently “semi-socialist” in a partisan sense; it’s a mix of responses to economic and social needs, though it did expand federal welfare and regulatory roles significantly.

Compliance with Article V has indeed waned—only 27 amendments total, with the last major one (26th, lowering voting age) in 1971. Reasons include political polarization making supermajorities harder, plus reliance on judicial and legislative workarounds. Whether this is “disregard” or evolution depends on one’s viewpoint, but your point underscores a real trend toward informal change.

The Current “Revolution” Against the Administrative State

Finally, your prediction of a counter-revolution with significant constitutional modifications echoes ongoing debates. Recent events, like Supreme Court rulings curbing agency deference (e.g., Chevron’s overturn in 2024’s Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo), challenges to federal overreach, and movements for reforms like term limits or balanced budgets, do suggest pushback against the administrative state. Comparisons to past revolutions—the Civil War amendments abolishing slavery (13th–15th, 1865–1870) and the Progressive/New Deal shifts—are apt in scale, as both involved profound societal restructuring.

That said, whether we’re in a full “revolution” is speculative and depends on future political outcomes. Proposals for a constitutional convention (under Article V) have gained traction in some states, targeting issues like fiscal restraints or executive power limits, but they face hurdles like ratification thresholds. If changes occur, they could indeed be as transformative as you suggest, potentially rolling back federal agencies or redistributive programs. However, history shows such shifts often involve compromise rather than wholesale reversal—e.g., post-New Deal America retained core elements while adapting. Amar’s book might offer optimism here: If the Constitution survived early crises through dialogue, it could navigate this one too, provided changes respect democratic processes.

Overall, your take thoughtfully extends Amar’s historical lens to critique modern trends, highlighting risks of straying from textual fidelity. It invites reflection on how to balance stability with adaptability in a changing world. If you’d like me to dive deeper into specific historical examples, Amar’s other works, or counterarguments from living constitutionalists, just let me know!