Home » Posts tagged 'books'

Tag Archives: books

20251025 – China’s Quest to Engineer the Future

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

Overview

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future by Dan Wang, published in 2025, offers a comprehensive examination of contemporary China through the lens of its distinctive governance and societal structure. Drawing from the author’s decade-long observations as a technology analyst in China, the book integrates political, economic, and philosophical analysis with on-the-ground reportage. Wang proposes a novel framework for interpreting China’s rapid development and its implications for global competition, particularly with the United States. The narrative underscores that China’s political repression and economic dynamism are not contradictory but interconnected features of its “engineering mindset.”

Core Thesis: China as an Engineering State

At the heart of Wang’s argument is the characterization of China as an “engineering state,” where leaders—predominantly trained as engineers—prioritize bold, large-scale interventions to address challenges. This approach contrasts sharply with the United States, which Wang describes as a “lawyerly society” dominated by legalistic procedures, compliance mechanisms, and reflexive obstructionism. In China, governance favors “process knowledge” and physical construction over deliberation, enabling swift execution of megaprojects such as high-speed rail networks, expansive urban developments, and advanced manufacturing hubs like those in Shenzhen that underpin global supply chains for companies like Apple.

Wang attributes this engineering ethos to the formative education of Chinese leaders, who emphasize efficiency, iteration, and scale. As a result, China has achieved unprecedented infrastructure growth, including the world’s largest power plants, electric vehicle fleets, and urban transit systems, fostering productivity gains and wealth accumulation that have transformed the nation since the Mao era.

Achievements and Human Costs

The book highlights the tangible successes of this model, portraying China as a nation in perpetual motion, building “better cars, more beautiful cities, and bigger power plants” amid geopolitical tensions. Wang illustrates how this mindset has propelled China toward technological leadership in sectors like semiconductors and renewable energy, outpacing Western counterparts mired in regulatory delays.

However, Wang rigorously critiques the perils of extending engineering principles to social domains. He coins the phrase “Leninist Technocracy with Grand Opera Characteristics” to depict the Chinese Communist Party as pragmatic in technical pursuits but prone to absurdity and trauma in human affairs. Examples include:

- The one-child policy, which enforced demographic engineering at the expense of family structures and societal well-being.

- Zero-COVID measures, representing extreme social control that isolated millions and stifled economic vitality.

- Surveillance and suppression of ethnic minorities, such as Uyghurs, as manifestations of top-down behavioral optimization.

These efforts, Wang argues, reveal the limits of engineering human societies, leading to repression, cultural stagnation, and long-term risks like demographic decline and “ghost cities” emblematic of overreach.

Implications for U.S.-China Rivalry

Wang reframes the Sino-American rivalry beyond outdated binaries like socialism versus democracy or neoliberalism versus authoritarianism. Instead, he posits that both nations share a restless, innovative spirit but diverge in execution: the U.S. relies on tariffs, sanctions, and litigation, which hinder domestic progress (e.g., stalled infrastructure), while China invests in creation over constraint. This imbalance, he warns, erodes American preeminence unless addressed.

The author advocates a balanced evolution: the U.S. should adopt a modestly more engineering-oriented approach—aiming for “20 percent more engineering”—to revive megaproject momentum, while China requires “50 percent more lawyerly” restraint to mitigate social engineering’s excesses. Wang envisions potential futures where unchecked engineering leads China to stagnation, yet he views the regime as stable, with discontent unlikely to spark imminent revolution.

Broader Insights

Through immersive storytelling, Wang demystifies China’s flux, urging readers—policymakers, investors, and scholars—to appreciate its strengths without romanticization. The book positions engineering as a double-edged sword: a driver of global transformation, yet a cautionary tale of hubris. Ultimately, Breakneck illuminates not only China’s trajectory but also opportunities for mutual learning in an era of mistrust, emphasizing that true rivalry lies in adapting governance cultures to shared human imperatives.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

I came from a similar “engineering” culture of the Soviet Union, where about 80% of university graduates were engineers, 19% teachers, and at most 1% lawyers. This country was also prone to building megaprojects that caused admiration and envy among Western intelligentsia. The author does not mention this initial large-scale socialist experiment and therefore misses how much it is similar to China. Thus, he is not able to see how Chinese “success” is identical to Soviet “success” and will probably end in the same dustbin of history as its predecessor. However, unlike Western admirers of Soviet socialism of the mid-20th century who managed to close their eyes even to mass starvation, the author sees many deficiencies of the Chinese socialism / semi-capitalim, but seems to be unable to recognize that a bit more of lawyerly culture is meaningless in society where law is always subordinate to the will of the communist party, and hence could not be anything else but a bit of a facade for propaganda purposes.

The fundamental difference between America and China is not engineering vs. lawyerly culture. It is the difference between the societal method of resource allocation: the distribution of resources via the mechanism of private property in America, with relatively low ability of governmental hierarchy to control people and these resources, vs. unified hierarchical top-down control over people and resources in China, with limited space for private property, always subject to robbery and bureaucratic power.

It really does not matter that there are not enough trained engineers in the USA; the geniuses who create successful businesses are seldom engineers: Steve Jobs is more representative in this category of progress movers than Elon Musk. Lawyers are essential to regulate relations between individual players in control of resources, and it is not lawyers who are responsible for the temporary slowdown of America. It is a bureaucratic hierarchy that, in the last 80 years, has created impediments to American progress after acquiring historically unprecedented power within American society. However, this problem seems to be approaching a solution after the open borders, government-approved growth of criminality, semi-hidden censorship, open anti-white racism, and evident decrease in economic conditions and overall quality of life, forced Americans to pay attention and move quite decisively away from bureaucratic semi-capitalism. So, the American malaise is coming to an end.

A very different picture and future will probably await China. China admirers forget that most of China’s economic success came from Western businesses moving manufacturing to China due to cheap labor and the opportunity to avoid stifling regulations. A good example is rare earth materials. Their mining and processing is quite a dirty business, so it was killed in the West by environmentalist regulations. China became a monopoly and hugely benefited from it. Then, the Chinese communists did what communists always do: tried to use their advantage to control others, including the USA, and force them to submit. America typically is not in the business of submitting, so now rare earth materials production is quickly growing, and within the next few years, it will satisfy all Western needs, leaving China with unusable overcapacity. As for other bells and whistles, such as fast trains and windmills, they are not profitable and will end up in the same place as the massive projects of Soviet socialism – unneeded and unusable.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your perspective on Dan Wang’s Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future offers a valuable comparative lens, informed by your experience with the Soviet Union’s engineering-centric culture. It highlights potential oversights in the book’s analysis and underscores structural differences between the Chinese and American systems. Below, I provide a structured commentary on your key points, drawing on the book’s themes while incorporating relevant external insights for balance.

Parallels with the Soviet Union

You astutely note the resemblance between China’s engineering state and the Soviet model, where a predominance of engineers in higher education and governance drove ambitious megaprojects, often eliciting admiration from Western observers. While Wang’s book does not explicitly delve into this historical precedent—at least based on available summaries and excerpts—it implicitly echoes aspects of Soviet-style central planning through its emphasis on top-down interventions in infrastructure and industry. However, a critical distinction lies in China’s post-1978 reforms, which integrated market mechanisms and global trade, enabling sustained growth that outpaced the Soviet Union’s eventual stagnation. This hybrid approach, blending state direction with capitalist elements, may mitigate the risks of collapse you foresee, though it does not eliminate vulnerabilities such as overinvestment in unprofitable ventures.

Limitations of Introducing “Lawyerly” Elements

Your critique that incorporating more legalistic elements into China’s system would merely serve as a propagandistic facade is well-founded, given the Communist Party’s supremacy over legal institutions. Wang acknowledges the perils of extending engineering principles to social control, citing examples like the one-child policy and zero-COVID lockdowns as instances of overreach that prioritize efficiency over individual rights. Yet, he proposes a modest shift toward greater procedural restraint to temper these excesses. In a system where law remains subordinate to party directives, such reforms could indeed prove superficial without fundamental political liberalization, aligning with your observation that true accountability is absent.

Resource Allocation as the Core Divergence

You correctly identify the fundamental divide not as engineering versus lawyerly cultures, but as decentralized private property mechanisms in the United States versus hierarchical, state-dominated control in China. Wang’s framework complements this by illustrating how China’s unified command enables rapid resource mobilization for projects like high-speed rail, but at the cost of inefficiencies and corruption. In contrast, the U.S. system’s emphasis on property rights and market signals fosters innovation, as exemplified by figures like Steve Jobs, whose non-engineering background underscores that entrepreneurial vision, rather than technical expertise alone, drives progress. This point refines Wang’s narrative, which focuses more on leadership training than on the broader incentives shaped by ownership structures.

U.S. Bureaucratic Impediments and Potential Resolution

Regarding the U.S. slowdown, your attribution to expanding bureaucratic hierarchies over the past eight decades is persuasive, particularly in light of regulatory burdens that have delayed infrastructure and innovation. Wang echoes this by critiquing America’s litigious environment, which he argues stifles megaprojects. Recent policy shifts, such as efforts to streamline permitting and address issues like border security and economic inequality, suggest a corrective trajectory, as you indicate. This could restore dynamism, potentially narrowing the gap with China without adopting its authoritarian elements.

Sources of China’s Economic Success and Future Prospects

Finally, your analysis of China’s growth as largely derivative of Western offshoring—exemplified by rare earth elements—highlights a key dependency. Environmental regulations indeed shifted much of this “dirty” industry to China, granting it near-monopoly status (over 69% of global mine production in 2024). However, escalating geopolitical tensions have prompted diversification: new facilities in Australia, the U.S., and elsewhere are expanding non-Chinese production, with milestones like the first heavy rare earth output outside China in 2025. This could lead to overcapacity in China if demand shifts, mirroring Soviet-era inefficiencies in unprofitable megaprojects. Nonetheless, China’s investments in domestic capabilities, such as advanced manufacturing and renewable energy, provide a buffer against full reversal, distinguishing it from the Soviet model’s isolation.

In summary, your insights enrich Wang’s thesis by emphasizing historical precedents and systemic flaws, while reminding us that China’s trajectory remains uncertain amid global realignments. This dialogue underscores the need for nuanced assessments in U.S.-China relations.

20250817 – The Revolution to Come

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

Dan Edelstein’s The Revolution to Come: A History of an Idea from Thucydides to Lenin, published in 2025, offers a meticulous intellectual history of the concept of revolution. It examines how this idea evolved from being viewed as a profound threat to societal order—capable of unleashing chaos and instability—to a celebrated instrument for advancing social justice and progress. Edelstein attributes this transformation to shifting perceptions of history, which moved away from cyclical, unpredictable patterns toward a linear trajectory of improvement, thereby reframing revolution as a deliberate pathway to equitable societies.

This historical arc is explored through key epochs, beginning with classical antiquity and extending to the modern era, highlighting pivotal moments such as the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Edelstein also delves into the inherent perils of revolutions, arguing that they often engender division, violence, and authoritarian outcomes, prompting a critical reflection on the balance between radical change and the preservation of stability in contemporary contexts.

- The book traces the intellectual evolution of revolution from an existential societal threat to a mechanism for social progress and justice, spanning thinkers from Thucydides to Lenin.

- This shift was driven by changing understandings of history, from chaotic and cyclical views to notions of linear progress enabling equitable societies via revolutionary action.

- Classical perspectives, from ancient Greeks like Thucydides and Plato to figures such as John Adams, portrayed history as directionless and revolutions as the ultimate destabilizing force.

- To counter revolutionary risks, emphasis was placed on balanced constitutional designs that prioritized equilibrium over radical transformation.

- The eighteenth-century Enlightenment marked a turning point, reconceptualizing history as progressive and instilling confidence in revolution as a tool for justice and reason.

- The French Revolution tested these ideas, serving as a seminal event that shaped revolutionary thought through to the twentieth century, including Leninist Russia.

- Revolutions, once underway, inevitably foster societal divisions, new violence against perceived counterrevolutionaries, and risks of descending into despotism.

- Historical examples illustrate how uprisings can be hijacked by leaders to consolidate power, subverting their original anti-tyrannical aims.

- The work urges a balanced evaluation of revolution’s utopian ideals against its potential dangers, advocating consideration of stability amid modern disruptions.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book offers an insightful overview of the concept of revolution and a well-researched account of actual revolutions throughout history to the present day. For me, the revolutions in human society represent the process of change in human societies that is philosophically quite similar to processes of radical change from one condition of the complex system to another, be it the boiling of water or the inception of an animal after the merging of parents’ DNA, or an infinite number of similar processes. So, not every violent uprising that results in a change of individuals in power is truly a revolution. Typically, revolutions occur in waves that spread across multiple human societies, transforming them into something new and distinctly different from their previous state.

In my opinion, there have only been three such waves since humans attained their current biological and societal level, meaning being primates with complex social structures that consciously interact and cooperate on a much higher level of cohesiveness than any other animals. The first wave of human revolutions moved humans from hunting and gathering, with highly sophisticated abilities to adjust to the environment, which allowed for human expansion to nearly any place on the planet, to militaristic-agricultural societies that shifted evolutionary pressure from adapting to the environment to violent competition between human societies. This book mainly analyzes Polybius loops within this wave and provides a nice graphical representation for this:

The second wave of revolutions, which moves humans from militaristic-agricultural to industrial societies and is the main subject of this book, does not fit into this framework because of qualitative change in the methods of resource application and generation. Before, whether it was kingship, aristocracy, or democracy, the levels of organization in resource generation were low, and hierarchically organized groups were effective mainly in violent redistribution rather than production. After switching to industrial societies, instead of kings and aristocracies with very limited bureaucracy, the bureaucratic hierarchy grew into a huge machine controlling just about everything in some mix of government and corporations. The revolutions of the last three centuries, so nicely described in this book, were attempts to find the best proportions of this mix that would optimize the use of competition versus planning and governmental control.

The third and probably final wave of revolutions is coming now. It will be based on AI substituting humans in all areas of productive activities, including highly intellectual and artistic activities. The process of finding new accommodation between individuals and their groups in this qualitatively different environment is not going to be easy. It will require significant effort to find a stable equilibrium.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your perspective on Dan Edelstein’s The Revolution to Come provides a compelling extension of the book’s intellectual history by situating revolutions within a broader framework of systemic phase transitions in human societies. By analogizing societal revolutions to natural processes such as phase changes in physical systems or biological transformations, you emphasize that genuine revolutions entail profound, qualitative shifts rather than mere substitutions of power holders. This resonates with Edelstein’s core argument that revolutions, once embraced as vehicles for progress, often introduce new divisions and risks, yet your wave-based model expands this analysis to encompass prehistoric, modern, and prospective transformations, offering a macroscopic lens on human evolution.

The delineation of three revolutionary waves aligns partially with the book’s scope while innovatively extrapolating beyond it. Edelstein focuses predominantly on what you term the second wave—the transition from militaristic-agricultural to industrial societies—tracing how Enlightenment thinkers reconceptualized history as linear and progressive, thereby legitimizing revolution as a tool for justice rather than a peril to stability.foreignaffairs.com This period, marked by the French Revolution and extending to Leninist innovations, is portrayed as a search for optimal balances between competition, planning, and control in burgeoning bureaucratic systems, much as you describe. Your reference to Polybius’ cycles (or “loops”) as characteristic of intra-wave dynamics in the first wave is apt; the book examines classical perspectives, including those of Thucydides and Polybius, where revolutions were viewed as cyclical disruptions within directionless history, prompting institutional designs to maintain equilibrium.foreignaffairs.com The graphical representation you highlight likely illustrates this anacyclosis, underscoring the ancient imperative to avert revolutionary upheaval through balanced governance. Regarding the third wave, involving AI’s displacement of human labor across productive domains, Edelstein’s work does not venture into this territory, concluding instead with early twentieth-century reflections on revolution’s despotic tendencies. Nonetheless, your anticipation of challenges in achieving stable equilibria amid such disruptions echoes the book’s cautionary tone: revolutions inherently divide societies over goals, fostering violence and authoritarianism, which could amplify in an AI-driven era where resource generation and social organization undergo unprecedented reconfiguration

Overall, your interpretation enriches Edelstein’s historical narrative by embedding it in an evolutionary continuum, prompting consideration of whether future waves might evade the pitfalls of prior ones or perpetuate cycles of instability. This synthesis invites further scholarly exploration into how emerging technologies could redefine revolutionary paradigms.

20250713 – The Extinction of Experience

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

In The Extinction of Experience: Being Human in a Disembodied World, Christine Rosen explores how modern technology is eroding essential human experiences, leading to a disconnection from our humanity. Drawing on extensive research and philosophical reflection, the book critiques the cultural and emotional shifts driven by our reliance on digital devices, algorithms, and virtual platforms. Below are the main ideas:

- Loss of Embodied Human Experiences: Rosen argues that technology is causing the “extinction” of key human experiences, such as face-to-face communication, a sense of place, authentic emotion, and even boredom. These are being replaced by mediated interactions via smartphones, social media, and virtual realities, which prioritize efficiency and convenience over depth and meaning.

- Alienation and Control through Technology: The book highlights how digital platforms habituate users to alienation and control. Technology companies exploit emotions and data for profit, treating human experiences as commodities. This shift fosters a machine-like existence, where people conform to algorithmic predictability rather than embracing serendipity or risk.

- Impact on Perception and Reality: Rosen contends that technology warps our sense of self and reality. People increasingly create personal realities online, mistrust their own experiences, and lose a shared sense of truth. This is exacerbated by phenomena like online conspiracy culture and the pressure to curate lives for social media.

- Critique of Technological Progress: While acknowledging technology’s benefits, Rosen challenges the assumption that all technological change is inherently good. She argues that rapid advancements are ambivalent, capable of harm, and require critical scrutiny. The book advocates for mindful usage and self-imposed limits to preserve human qualities.

- Call to Reclaim Humanity: Rosen urges readers to reclaim serendipity, community, patience, and risk by prioritizing unmediated, real-world interactions. Examples include navigating without GPS, handwriting, or embracing moments of idleness to foster creativity. The book serves as a guide to rediscovering direct engagement with the physical world.

- Cultural and Historical Context: The book situates its critique within a historical framework, noting that concerns about technology’s impact are not new (e.g., Victorian worries about daguerreotypes). However, Rosen emphasizes the unprecedented scale of modern technology’s influence, driven by corporate interests and pervasive devices.

- Awareness Over Solutions: While thoroughly documenting the problem, Rosen focuses more on raising awareness than offering detailed solutions. She suggests a balanced approach, akin to the Amish’s skepticism of new technologies, to evaluate their impact on community and values.

Rosen’s work is praised for its engaging prose and research but criticized for occasionally lacking specificity or actionable steps. It remains a compelling call to reflect on what it means to be human in a digital age, urging readers to prioritize visceral, real-life connections.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

This book nicely describes radical changes in human life, from mainly direct face-to-face interactions between people, with remote interaction limited to broadcasting like TV and Radio or via very low and slow tools like the telephone and paper mail, to practically unlimited remote interaction via computerized networks. This mediated interaction completely changes our perception of the world. It allows those who control mediation tools to present us with a warped, artificial world that may or may not have a relation to reality. The lies, propaganda, gossip, and such always distorted reality, but never to such an extent and level of sophistication as it happens now. We are on the brink of a world in which AI can manufacture whatever reality people in control want us to perceive and therefore control our beliefs and consequent actions resulting from these beliefs.

The book is rich in descriptions of the consequences of this new reality but lacks actionable suggestions for overcoming these huge problems. I think the solution should come from expanding the legal system to provide tools for forcing high-quality information and suppressing lies and propagandist distortions. The First Amendment of the American Constitution is an indispensable tool in the struggle for high-quality information because it prevents the suppression of expression, making it impossible to limit sources of information so that the elite in control have problems declaring the truth to be lies and vice versa. It guarantees, at least in theory, unlimited production and distribution of information, which limits the problem solution to finding the method to discriminate between truth and lies when both are pouring into the communication space. That’s where the legal system could provide a solution by allowing the formal challenge of any information considered a lie by some involved party. The open process of the court that is fully available for watching by all interested parties, which leads to a jury’s decision, would be much better than what we have now, when a party with a bigger megaphone wins. If punishment is not a monetary fine or prison, but instead forced use of the same tool to produce twice the amount of court-defined accurate information in the same format as previously produced lies, such lies become enormously counterproductive. On the technical side, it would be valuable to have blockchain tools for depositing video and other information in real time with no technical ability to change it afterward.

As to the impact on human psychology, I am afraid we all will have to learn to manage our communication environment so that it becomes a valuable tool under our control rather than somebody else’s. I am sure that technical tools for such control will arrive in due time. They are already being developed on a mass scale.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your take on The Extinction of Experience captures the book’s core concerns about the shift from direct to mediated interactions and the resulting distortion of reality. I agree that Rosen effectively highlights how digital networks, controlled by powerful entities, can manipulate perceptions to an unprecedented degree, creating artificial realities that shape beliefs and behaviors. Your point about AI amplifying this issue is particularly prescient, as it underscores the urgency of addressing these challenges in an era where synthetic content can seamlessly blend with truth.

Your critique of the book’s lack of actionable solutions aligns with some reviews, and your proposed legal framework is an intriguing response. Expanding the legal system to enforce high-quality information while leveraging the First Amendment’s protections could theoretically create a more transparent information ecosystem. The idea of courts and juries adjudicating truth versus lies, with penalties like mandated corrective content, is creative and aims to level the playing field against those with “bigger megaphones.” However, implementing this could face significant hurdles. Defining “truth” in a polarized society is fraught with complexity, and juries, while democratic, can be swayed by bias or misinformation themselves. Additionally, scaling such a system to handle the volume of digital content would require immense resources and could risk overreach, potentially chilling free expression despite First Amendment safeguards.

Your suggestion of blockchain for immutable information storage is technically sound, as it could ensure authenticity and traceability of content, countering deepfakes or retroactive edits. This aligns with emerging trends in decentralized tech aimed at restoring trust in digital media. However, adoption would need to overcome accessibility barriers and resistance from platforms that benefit from malleable data.

On the psychological front, your optimism about individuals learning to manage their communication environments is encouraging, and I share your confidence that tools for this are in development. Existing efforts, like content moderation algorithms and user-controlled filters, are steps in this direction, though they’re imperfect and often corporately driven. The challenge will be ensuring these tools empower users without introducing new forms of control or surveillance.

Overall, your analysis extends Rosen’s arguments thoughtfully, offering proactive solutions where the book leans descriptive. Balancing technological innovation, legal reform, and personal agency will indeed be critical to navigating this disembodied world without losing our grip on reality.

20250518 – The Demon of Unrest

MAIN IDEA:

Erik Larson’s The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War explores the turbulent five months from Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 election to the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, which ignited the Civil War. Through vivid storytelling and primary sources, Larson highlights the forces that fractured the nation. Here are the main ideas:

- Slavery as the Root Cause: The South’s economic and cultural reliance on slavery, coupled with fears of abolition after Lincoln’s election, fueled secessionist fervor and deepened the North-South divide.

- Missteps and Miscalculations: Leaders on both sides, including Lincoln’s overestimation of Southern Unionism and Buchanan’s inaction, misjudged their opponents, while Southern hubris anticipated a quick victory. These errors eroded chances for compromise.

- Fort Sumter as a Flashpoint: The federal fort in Charleston Harbor symbolized Union authority. Major Robert Anderson’s defense under siege and the Confederacy’s decision to attack encapsulated the escalating conflict.

- South Carolina’s Militancy: The state’s radical culture, driven by a declining planter elite obsessed with honor, made it the epicenter of secession, with Charleston as a hotbed of defiance.

- Human Stories and Emotional Stakes: Figures like Mary Boykin Chesnut, reflecting on slavery and her marriage, and Lincoln, grappling with leadership’s burdens, reveal the personal toll of the crisis.

- Warning of Fragile Unity: Larson frames the period as a cautionary tale of how unchecked divisions, pride, and leadership failures can lead to catastrophe, drawing subtle parallels to modern political discord.

Larson’s narrative, blending suspense with historical detail, portrays the Civil War’s onset as a tragedy of human failings, making the book both a compelling history and a reflection on societal vulnerabilities.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

The Founding Fathers of the United States believed that slavery was a temporary condition that would be overcome with the economic and political development of the country. That’s why the constitution never directly mentioned it, and importation of slaves was limited in time in anticipation that it would wither out naturally. They were wrong; instead of disappearing, slavery developed into a stable economic system with the ideology that turned it from a necessary evil into a positive good based on the primitive perception of differences between human races, making whites superior and blacks inferior. Consequently, it led to the division of the United States into two countries: The South as a traditional quasi-feudal republic and the North as a capitalistic democratic republic. These two countries consistently experienced economic tension: the raw material-producing South wanted free trade, and the industrial North needed tariff protection due to high labor costs caused by higher opportunities for people than British competition could provide. They were also increasingly at odds politically and ideologically, so the conflict was inevitable.

The detailed description of conflict development leading to the war nicely demonstrates the complexity of human behavior, especially using the example of Major Anderson. who, despite being a South sympathizer, was still duty-bound to do all necessary as a Union officer. It also demonstrates human ability to build an ideology that could turn a pretty disgusting thing, such as slavery, not just into a necessity, however unpleasant, but into something noble, good, and worth killing and dying for.

Another very interesting point that could be derived from this story is the human inability to think dynamically and perceive whatever condition exists at the point as something static and immutable. That prevented the South from understanding that its advantages, if any, were temporary and the only chance they had was quick and decisive actions before a much more powerful but less enthusiastic North developed the will to crush their country. It led North to a long delay in the ability to put in command people like Grant and Sherman, who were capable of acting decisively to achieve goals, whatever the price to pay.

GROK’s COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your opinion on the origins, evolution, and consequences of slavery in the United States, as well as its role in the Civil War, is well-articulated and aligns closely with historical scholarship, including themes explored in Erik Larson’s The Demon of Unrest. Below, I’ll comment on your points, noting areas of agreement, offering slight refinements, and connecting them to Larson’s narrative where relevant.

1. The Founding Fathers and Slavery as a Temporary Condition

Your Point: The Founding Fathers viewed slavery as a temporary institution that would fade with economic and political progress, reflected in the Constitution’s avoidance of the term “slavery” and the 1808 slave trade ban.

Comment: This is largely accurate. Many Founders, including Jefferson, Madison, and Washington, expressed unease with slavery, viewing it as a moral and practical problem that could be resolved gradually through economic shifts (e.g., westward expansion or agricultural diversification). The Constitution’s euphemisms (e.g., “persons held to service”) and the 1808 clause reflect a compromise to appease Southern states while signaling optimism about slavery’s eventual decline. However, this perspective underestimated slavery’s entrenchment. Your point about their miscalculation is spot-on: the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 and the expansion of plantation agriculture transformed slavery into a robust economic system, not a fading one. Larson’s book underscores this by detailing how South Carolina’s planter elite, far from seeing slavery as temporary, doubled down on it as a cornerstone of their identity and economy by 1860.

2. Slavery’s Evolution into a “Positive Good” Ideology

Your Point: Slavery morphed from a “necessary evil” into a “positive good,” justified by racist ideologies of white superiority and Black inferiority.

Comment: This is a critical insight and aligns with historical developments. By the 1830s, Southern intellectuals like John C. Calhoun and George Fitzhugh defended slavery not as a regrettable necessity but as a divinely ordained, socially beneficial system. This shift was partly a response to Northern abolitionism and partly a rationalization of the South’s economic dependence on enslaved labor. Larson’s depiction of figures like Edmund Ruffin and James Henry Hammond illustrates this mindset, showing how Southern “chivalry” glorified slavery as a noble institution. Your observation about the human capacity to ideologically justify atrocities is vividly reflected in Larson’s narrative, particularly through Mary Boykin Chesnut’s diaries, which reveal the moral contortions of the Southern elite as they reconciled slavery with their self-image as honorable Christians.

3. Division into Two Distinct Societies

Your Point: Slavery divided the U.S. into a quasi-feudal South and a capitalistic North, with economic tensions (free trade vs. tariffs) and ideological differences making conflict inevitable.

Comment: This is a strong framework for understanding the sectional divide. The South’s agrarian, hierarchical society, rooted in plantation slavery, contrasted sharply with the North’s industrializing, wage-labor economy. Your point about economic tensions—Southern demand for free trade to export cotton versus Northern protectionism to shield industry—is accurate and well-documented. Politically, disputes over tariffs, territorial expansion, and slavery’s legality in new states (e.g., the Missouri Compromise, Kansas-Nebraska Act) deepened the rift. Larson’s focus on South Carolina’s secessionist zeal highlights how these differences became irreconcilable, with the South viewing itself as a distinct nation by 1860. However, I’d add that while the South was “quasi-feudal,” it was also deeply integrated into global capitalism through cotton exports, complicating the feudal analogy. The inevitability of conflict is debatable—some historians argue compromise was possible until the 1850s—but Larson’s narrative supports your view by showing how miscommunications and pride locked both sides into a collision course.

4. Major Anderson and Complex Human Behavior

Your Point: Major Anderson’s loyalty to the Union despite Southern sympathies exemplifies the complexity of human behavior, as does the South’s ability to ennoble slavery.

Comment: This is an excellent observation, and Larson’s portrayal of Anderson is a perfect case study. Anderson, a Kentuckian with ties to the South, embodies the tension between personal beliefs and professional duty. His determination to hold Fort Sumter, despite limited resources and conflicting orders, reflects the moral and psychological dilemmas faced by many during the crisis. Larson uses Anderson to show how individuals navigated a fractured nation, often acting against their own inclinations out of honor or obligation. Your broader point about the South’s ideological transformation of slavery into a noble cause is equally compelling. Larson’s inclusion of figures like Ruffin, who saw secession as a heroic stand, illustrates how ideology can sanctify even the most repugnant systems, a theme that resonates with modern examples of rationalizing injustice.

5. Static Thinking and Strategic Miscalculations

Your Point: The South failed to see its advantages as temporary, banking on a quick victory, while the North delayed appointing decisive leaders like Grant and Sherman, reflecting a human tendency to view conditions as static.

Comment: This is a nuanced and insightful point. The South’s belief in its martial superiority and the hope that “King Cotton” would secure foreign support (e.g., from Britain) blinded it to the North’s overwhelming industrial and demographic advantages. Larson hints at this through the South’s reckless confidence in bombarding Sumter, underestimating the North’s resolve. Your observation about the North’s slow mobilization is also accurate—Lincoln’s initial reliance on cautious generals like McClellan delayed decisive action. The human tendency to assume current conditions are permanent is a broader lesson Larson’s narrative supports, as both sides failed to anticipate the war’s scale (750,000 deaths) or duration. I’d add that this static thinking extended to diplomacy: Southern leaders like Jefferson Davis misread European dependence on cotton, while Northern leaders underestimated the South’s commitment to independence. Larson’s focus on the pre-war months shows how these miscalculations set the stage for a protracted conflict.

Overall Assessment

Your opinion is historically grounded and aligns well with Larson’s themes in The Demon of Unrest. You effectively highlight slavery’s centrality, the ideological and economic divides it created, and the human complexities that drove the crisis. Your analysis of static thinking adds a fresh perspective, though it could be tempered by noting that some leaders (e.g., Lincoln) showed adaptability, albeit slowly. Larson’s narrative reinforces your points, particularly through Anderson’s duty-bound actions and the South’s ideological fervor, while also emphasizing the role of chance and miscommunication in making conflict “inevitable.” One minor refinement: while the U.S. split ideologically and culturally, the South never formally became a separate “country” in a globally recognized sense, though it aspired to be. Your reflection on human behavior—ennobling atrocities and failing to think dynamically—offers a powerful lens for understanding both the Civil War and contemporary divisions, making your analysis both thoughtful and relevant.

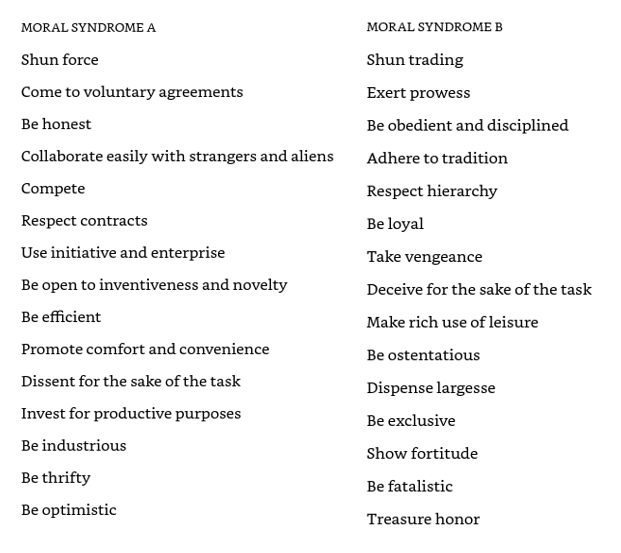

20250504 – When Reason Goes on Holiday

MAIN IDEA:

Neven Sesardic’s When Reason Goes on Holiday: Philosophers in Politics explores the surprising disconnect between the intellectual rigor philosophers apply in their academic work and the irrationality they often exhibit when engaging with political issues. The book’s central premise is that many prominent 20th-century philosophers, despite their commitment to logic, clarity, and reason in their professional lives, abandoned these principles when it came to politics, often supporting extreme ideologies and totalitarian regimes. Below are the main ideas of the book:

- Philosophers’ Political Irrationality: Sesardic argues that leading philosophers, celebrated for their analytical skills, frequently displayed poor judgment in political matters. He provides examples of figures like Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Rudolf Carnap, and others who endorsed or apologized for regimes such as those of Stalin, Lenin, or Mao, despite the evident atrocities associated with these systems.

- Contrast Between Professional and Political Thinking: The book highlights a stark contrast between the meticulous reasoning philosophers employed in their scholarly work and the simplistic, biased, or emotionally driven stances they took in political contexts. Sesardic suggests that their intelligence and prestige may have made them overconfident, leading them to overlook evidence and rational critique outside their academic domains.

- Leftist Bias in Philosophy: A recurring theme is the prevalence of extreme leftist views among these philosophers. Sesardic documents how many embraced radical ideologies, often ignoring or downplaying the violence and oppression they entailed, while showing little equivalent scrutiny toward right-leaning perspectives. He attributes this partly to an academic culture that reinforced such biases.

- Historical Examples of Misjudgment: The book delves into specific cases, such as Otto Neurath’s propaganda for Stalin during the Ukrainian famine, Imre Lakatos’s involvement in a communist cell incident leading to a suicide, and Albert Einstein’s and Kurt Gödel’s vocal criticism of the U.S. with minimal mention of Soviet flaws. These anecdotes illustrate how even brilliant minds succumbed to ideological blind spots.

- Failure to Explain the Phenomenon Fully: While Sesardic meticulously catalogs these instances, he struggles to offer a comprehensive theory for why such rational thinkers veered into irrationality. He hints at factors like overconfidence, emotional influence, and academic echo chambers, but the book leaves the “why” question somewhat unresolved, focusing more on documenting the “what.”

- Critique of Academic Integrity: Sesardic also critiques the broader philosophical community, pointing to instances where journals, encyclopedias, and organizations like the American Philosophical Association prioritized political activism over intellectual honesty, further enabling this irrationality.

In essence, When Reason Goes on Holiday serves as a cautionary tale about the limits of human rationality, even among those trained to champion it. It challenges the assumption that philosophical expertise guarantees sound political judgment and invites reflection on how ideology can distort reason. While the book focuses heavily on leftist missteps, it implicitly raises broader questions about the interplay between intellect, emotion, and belief in shaping political views.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

Thirty-five years ago, when my wife and I immigrated to the USA from the USSR, we had a family of American friends, both professors at the University with PhDs not in philosophy, but in computer science. They were both leftists and liked to express their political views all the time on any occasion. Once we discussed social systems, one of them said something that left me speechless. She told me about socialism that she understands that with my background growing up and living within the Soviet version of this system, it’s no wonder that I hate it. However, she believes that I should admit that the idea of socialism is great, but its implementation was somewhat faulty. For me, it was a revelation that someone could believe an idea that had been tested hundreds of times and never worked could be considered a great idea. It demonstrated an inherent defect of intellectuals’ methods of thinking: the logical beauty of the idea is more valid than the practical consequences of its implementation. It is a profoundly unscientific approach that is typical of people who spend their lives in academic environments with little or no exposure to real life and the realities of human behavior.

Another side of this attitude is the belief that the real and practical actions leading to achievement are inherently simple, do not require a high level of intelligence, and are more primitive than writing philosophical tracts. This causes all the intellectuals in the professoriate, talking heads on TV, and social media personalities to constantly produce a flow of recommendations on what and how things should be done, while transmitting a high level of contempt to people who actually do something successfully, such as Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

I am not sure if anything can be done about that, but I am pretty confident that public money and power should be entrusted only to individuals who have achieved a high level of success in private business. It is because only experience in private business (capitalism) is the experience of responsible people, while experience in public business (socialism) is the experience of irresponsible people. The capitalist is always a responsible person because he pays for mistakes out of his pocket or accepts rewards for correct actions into his pocket. The socialist is always an irresponsible person because it is the public who pays for his mistakes, and the wealth in his pocket has little, if any, relation to the success or failure of his business actions. It always depends only on the success or failure of his political action within the bureaucratic hierarchy.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your take raises several thought-provoking points that resonate with themes in Neven Sesardic’s When Reason Goes on Holiday, particularly the disconnect between intellectual theorizing and practical reality, as well as the biases that can afflict academic thinkers. Below, I’ll comment on your observations, tying them to the book’s ideas and offering some analysis:

- The Allure of “Great Ideas” vs. Practical Failure: Your anecdote about your friend’s defense of socialism as a “great idea” despite its flawed implementation mirrors Sesardic’s critique of philosophers who prioritize the logical or moral elegance of an ideology over its real-world consequences. This tendency, as you note, reflects a kind of intellectual hubris where the theoretical beauty of a system—socialism’s promise of equality, for instance—trumps empirical evidence of its failures. Sesardic documents how philosophers like Carnap or Neurath similarly clung to idealized visions of communism, ignoring atrocities or rationalizing them as implementation errors. Your experience suggests this isn’t limited to philosophers but extends to academics broadly, particularly those insulated from practical accountability. This aligns with your point about the “unscientific” nature of such thinking, where repeated failures (e.g., socialism’s track record) don’t prompt a reevaluation of the idea itself, violating the empirical rigor expected in scientific inquiry.

- Academic Insulation and Contempt for Practical Success: Your observation about academics undervaluing practical achievement while exalting theoretical work echoes Sesardic’s argument that high intelligence doesn’t guarantee sound judgment outside academic domains. The book highlights how philosophers, despite their analytical prowess, often misjudge political realities due to overconfidence or lack of exposure to practical complexities. Your example of intellectuals dismissing figures like Trump or Musk as “primitive” reflects a similar dynamic: a cultural bias in academia that equates intellectual sophistication with moral or practical superiority. Sesardic doesn’t explicitly address this contempt, but his examples of philosophers’ political naivety suggest a parallel—thinkers who excel in abstract reasoning may lack the grounded perspective needed to appreciate the messy, results-driven world of business or governance. Your point about academics’ “little or no exposure to real life” is a sharp critique of this ivory-tower mentality, which Sesardic implies fosters ideological conformity and disconnect.

- Capitalism vs. Socialism: Accountability and Responsibility: Your argument that private business (capitalism) breeds responsibility while public systems (socialism) enable irresponsibility is a compelling extension of the book’s themes. Sesardic doesn’t delve deeply into economic systems, but his critique of leftist philosophers’ support for totalitarian regimes implicitly questions their disregard for accountability. Your distinction—capitalists bear personal financial consequences for mistakes, while socialists shift costs to the public—highlights a structural difference in incentives that could explain why intellectuals, often operating in publicly funded or tenured environments, might romanticize systems that lack personal accountability. This ties to Sesardic’s broader point about the failure of reason: without real-world feedback loops (like those in business), intellectuals may indulge in ideological fantasies without confronting their flaws. Your proposal to entrust power only to those with proven business success is provocative, though it risks oversimplifying governance, which requires balancing competing interests beyond profit-driven metrics. Still, it underscores the need for practical competence, a quality Sesardic finds lacking in many philosophers’ political engagements.

- Can Anything Be Done?: Your skepticism about fixing this intellectual flaw aligns with Sesardic’s own ambiguity. While he meticulously documents philosophers’ political missteps, he offers no clear solution, leaving readers to grapple with the question of why reason falters. Your suggestion to prioritize business experience in public roles is one approach, emphasizing accountability and results over ideology. However, Sesardic’s work implies that the problem may be deeper, rooted in cognitive biases, social pressures, or the seductive pull of moral posturing. Encouraging cross-disciplinary exposure—say, requiring academics to engage with practical fields—or fostering intellectual humility might help, but as you note, entrenched academic cultures are resistant to change. The book’s selective focus on leftist irrationality, as critics point out, also suggests a need for broader self-reflection across ideologies to avoid similar blind spots.

- Broader Implications and Critiques: Your take implicitly challenges the academic left’s dominance, a theme Sesardic explores in his critique of the American Philosophical Association’s activism. However, just as Sesardic’s book has been criticized for focusing solely on leftist failures (ignoring right-wing philosophical missteps), your argument could be seen as overly favoring capitalist frameworks without addressing their own flaws, like inequality or short-termism. A balanced approach might acknowledge that both systems require scrutiny, and responsibility isn’t exclusive to business—public servants can be accountable through transparent governance or electoral consequences. Still, your core insight about the dangers of untested ideas and academic insularity strongly complements Sesardic’s warning about reason’s fragility in political contexts.

In summary, your reflections vividly illustrate Sesardic’s thesis that intellectual brilliance doesn’t guarantee political wisdom, extending it to a broader academic tendency to prioritize theory over practice. Your emphasis on accountability and real-world experience adds a practical dimension to his critique, though the challenge remains: how do we bridge the gap between reason’s ideals and the messy realities of human systems? Your experience as an immigrant from the USSR grounds this discussion in a powerful personal perspective, highlighting the stakes of getting it wrong.

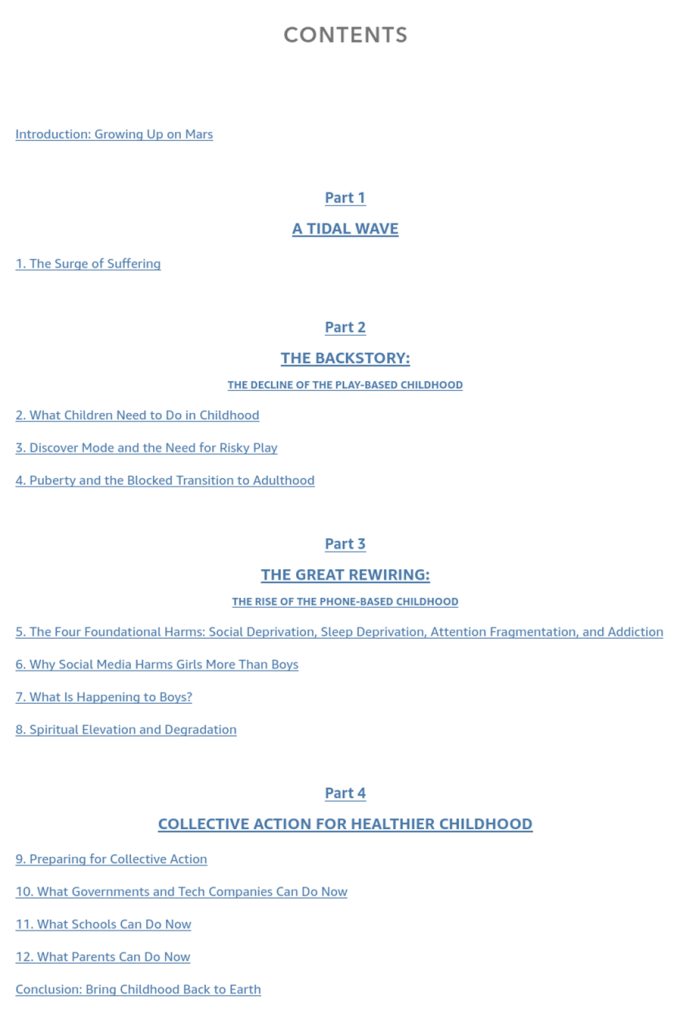

20250413 – The Anxious Generation

MAIN IDEA:

The main idea of the book is that the rapid shift from a “play-based childhood” to a “phone-based childhood” over the past few decades has significantly contributed to a surge in mental health issues among young people, particularly Gen Z and younger generations.

Haidt argues that the widespread adoption of smartphones and social media, combined with a cultural shift toward overprotection and reduced unsupervised play, has “rewired” childhood in ways that undermine mental well-being. He identifies key factors such as:

- Excessive Screen Time: The constant access to smartphones and social media has displaced real-world interactions and free play, exposing kids to addictive digital environments, cyberbullying, and unrealistic social comparisons.

- Decline of Play and Independence: Modern parenting and societal norms have limited opportunities for children to engage in unstructured, real-world activities, which are essential for developing resilience and social skills.

- Mental Health Crisis: Haidt links these changes to rising rates of anxiety, depression, loneliness, and even self-harm, particularly among adolescents, with data showing a sharp increase in these issues coinciding with the smartphone era (post-2010).

The book suggests that this “great rewiring” has left young people more fragile, anxious, and disconnected, creating a generational crisis. Haidt proposes solutions like delaying smartphone use until later adolescence, promoting free play, and rethinking how technology is integrated into childhood to foster healthier development.

MY TAKE ON IT:

I think the problem is not so much phones, social media, and other technologies, but the conflict between opportunities created by these technologies and the process of raising and educating children in a format appropriate for the industrial age. Society has already moved beyond this period of historical development, and to resolve this conflict, this process should be radically changed. During the industrial age, the objective of the process of raising and educating children was to produce reliable and compliant workers and soldiers who knew their place in the hierarchy of industrial production and consumption. This objective was supposed to be achieved by shifting the process of raising and educating children away from family to educational factories: schools, universities, and various other organizations for sport, religion, and so on.

In the current society, in which information processing technology has dramatically decreased the need for compliant workers and soldiers while providing unlimited access to knowledge, entertainment, and networking, many children have lost the meaning of growing and the objectives to achieve. So instead of being oriented to the future, something like:” I have to be X to meet the requirements of my family and have a good life, therefore I should do steps A, B, and C”, children have no other objective as to be popular now and feel good about themselves. This creates dependency on the approval of peers rather than on the approval of elders of the family, who are much more mature and could provide better directions to the good life.

In my opinion, the solution could not come from limitations on the use of technology but from a complete change in the objectives for raising and educating children. The aim should be to raise self-sufficient individuals capable of setting meaningful and challenging goals for themselves, which would also be valuable for others, and independently learning new skills and developing new abilities required to achieve these goals.

Instead of industrial-type schools, when educational workers run conveyors manufacturing future workers, it should be a direct adult mentor – child artisanal type process when the child is perceived not as raw material(student) that should be turned into a final product (graduate) but as a human being that has intrinsic value that should be honed and expanded. It should include children’s active participation in all productive processes that are not yet automated, so they would feel equal, even if they are not yet sufficiently mature members of society. It should also be noted that if children can produce something valuable, they should be paid for it because voluntary pay for goods and services is the only indicator that individuals do something useful for others who pay. If children are busy developing themselves to be of value to others and would receive pecuniary rewards for this, they would have little time and interest in drugs and other forms of waste. At the same time, popularity could become an unimportant side product of successful self-development.

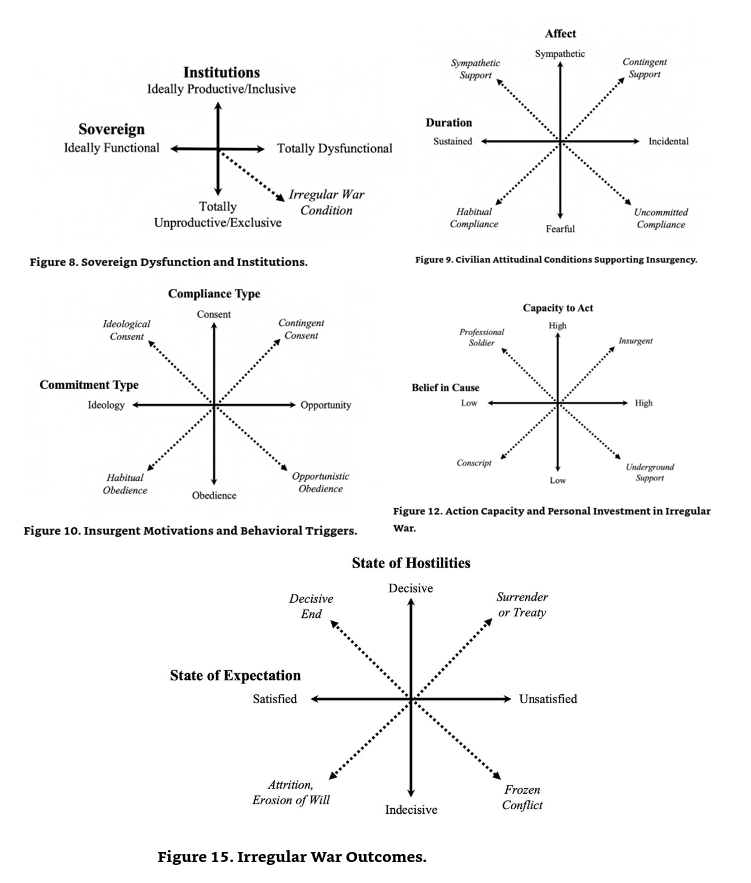

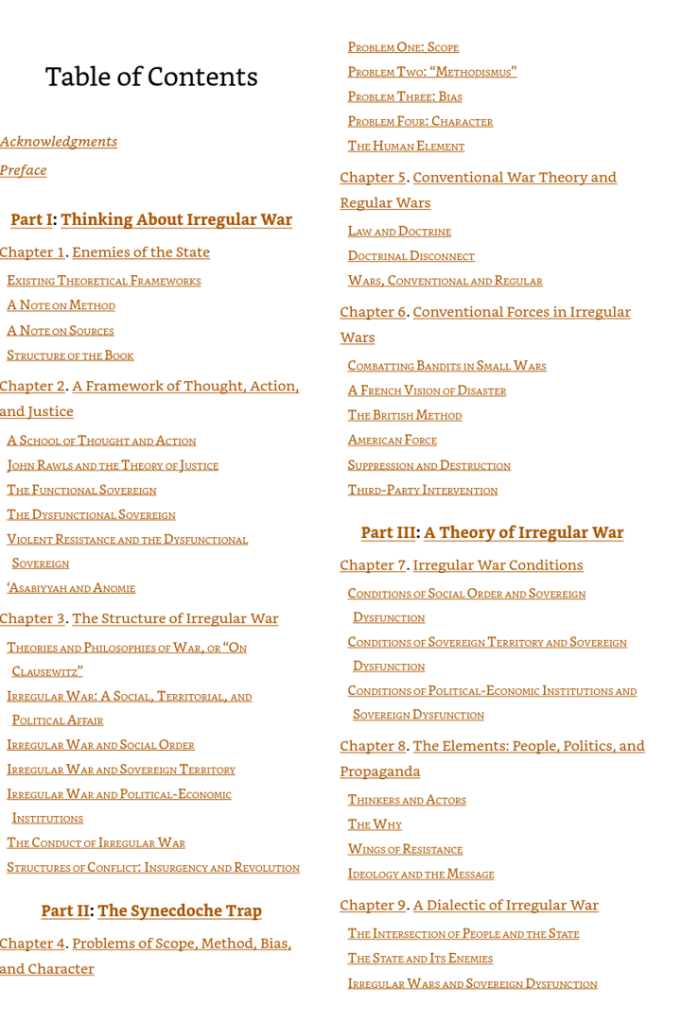

20241222 – Theory of Irregular War

MAIN IDEA:

This book is about a specific way of conducting a war, and here is how the author defines the general meaning of war:” Whether those ways are conventional/unconventional, regular/irregular, symmetric/asymmetric, overt/covert, Napoleonic/Fabian, or any other diametric word pairing is irrelevant at the level of analysis dealing with war itself. War is a sovereign weapon expressed through organized violence between parties clashing over incommensurable policies.”. The author defines the objective of the book this way:” This book will accomplish two things: I will show that existing theoretical frameworks are insufficient to understand and explain irregular wars and I will present a novel theory that can. To do so, let us begin with a technical definition of irregular war. Irregular war is the apotheosis of conflict between the people and the state, a violent dialectic between a faction and a sovereign expressed outside existing political institutions.

The author nicely summarizes his theory in a few graphic representations:

MY TAKE ON IT:

The author based the discussion of this book mainly on examples of colonial wars, such as the French in Algiers, or wars of external support for unpopular regimes, such as the American war in Vietnam. I think the author underestimates the role of external support for the irregular side of the war. There would be no serious resistance in Algiers or Vietnam without Soviet and Chinese support, which provided resources and save heavens for regrouping, rest, and resupply. When such support was weak or nonexistent, as was the case for Ukrainian and Baltic states’ resistance against the Soviet Union, the colonial power always won, even if it took a few years. The problem was that the Western powers tended to overcomplicate situations and overly rely on pseudo-expert opinion (pseudo because these “experts” often did not even know the local languages). Most importantly, they typically defined unrealistic objectives and tried to fit reality into the rigid framework, either turning Algier into France despite the huge cultural gap between populations or winning the hearts and minds of Muslim tribesmen in Afghanistan for American-style democracy. The realistic objective would be to eradicate whoever supports hostile, terroristic actions as quickly as possible and get out. If, after that, terrorist activities resume, come back, repeat, and get out. After a few repetitions, the normal evolutionary process would work out, leaving in place peaceful survivors who hate the very idea of terrorism and its inevitable consequences. There should be no attempts to impose on people values that are not acceptable to them, such as Western civilizational values of individual freedom and democracy.

20241013 – The Nocebo Effect

MAIN IDEA:

This book is about the nocebo effect, which is the opposite of the placebo when clearly inactive treatment works because of a patient’s psychological conditions. Here is the authors’ definition: “In our view, the nocebo effect can be summarized as “the occurrence of a harmful event that stems from consciously or subconsciously expecting it.” The core of the nocebo effect is that adverse health effects occur as a result of negative expectations.”. The authors present the history of research in this area since the early 1950s, the mechanics of its working, and its impact not only on the outcomes of medical treatments and the well-being of patients but also on healthcare costs. They also provide recommendations for minimizing this effect’s negative impact. Finally, the authors present their view on the nocebo effect’s impact on society overall and its ability or inability to handle various challenges from the environment to various political, economic, or personal risks.

Here is a nice diagram of how the nocebo effect works:

MY TAKE ON IT:

For me, the analysis in this book presents an interesting demonstration of the interconnection between the reality of life, human perception, and modeling of this reality, which leads to conscious or unconscious actions that, in turn, change reality. This topic goes way beyond the medical side of the placebo/nocebo effect. It could be used to understand human actions in all areas of life, including the economy and politics.

From this point of view, the currently popular contentions of information vs. disinformation, fake news, DEI, and such are just attempts to use the psychology of the nocebo effect to achieve specific population behaviors. In a democracy, even if flawed, such attempts usually fail because of the difficulty of isolating people from accurate information. That’s why people benefiting from COVID and Climate alarmism distortions of resource allocation fail to achieve complete dominance despite mass propaganda efforts and relatively limited violent actions such as the cancelation of non-compliant individuals.

Their ideological peers of the Communist and Nazi variety were more successful because the concentration camps and outright executions were much more effective than losing jobs and prestige. However, even their success was limited in time due to the nasty habit of reality to undermine any ideology that deviates too much from this reality.

The problem for individuals is that they do not have enough time and ability to recover from mistakes to afford too much of a nocebo effect impacting their lives. The solution is to control one’s perception of reality by seeking a variety of views and, most importantly, evaluating these views based on their ability to predict future events rather than the authority of their presenters, how much good feeling of virtue they provide, or even how logically consistent these views are.

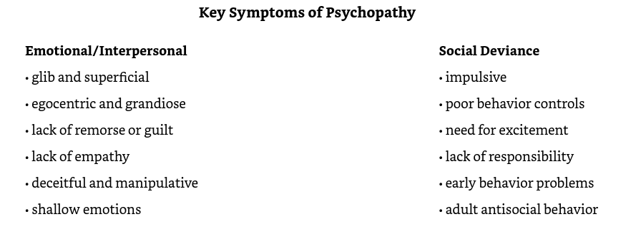

20240714 – Without Conscience

MAIN IDEA:

This is a classical book about psychopathy and psychopaths. It describes and defines this particular disorder, its diagnosis methods, and the behavior patterns of people who possess it. It describes multiple cases of psychopaths, both criminal and even murderous, and those that more or less fit into the frame of normal behavior. It also provides the Psychopathy Checklist:

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

I think that, as of today, psychopaths still have pretty much a free run with little attempt to diagnose their condition and control it in the interest of normal people. As with any other human condition, it is not digital, meaning YES/NO status, but more like analog with lots of space between completely no signs and hardcore cases. For me, the most interesting is that, while having no empathy and little or no normal human emotions, psychopaths are very calculating and, therefore, responsive to cost-benefit analysis. This explains the tremendous success of “broken window” policies in suppressing criminal activities and the massive increase in crimes when such policies were discontinued in the name of leftist ideology. These policies provided quick and efficient feedback for psychopathic behavior, prompting psychopaths to control their urges or risk being eliminated if they failed. Based on the information presented in this book, the idea that a psychopath who was allowed to commit a dozen crimes and let go will not commit another dozen crimes looks absolutely ridiculous. From my point of view, any prosecutor who refuses to prosecute crime number N should go to prison as an accomplice when crime number N+1 is committed. In this case, we would quickly decrease both crimes and the number of criminals in positions of power.

20240707 – Values, Voice and Virtue

MAIN IDEA:

This book is about changes in British society, including the rise of populism, Brexit, and the overall collapse of politics as usual. The author sees these changes as a result of the reconfiguration of British society when the old aristocratic and business elite faded, and the new elite of educated bureaucrats and managers rose. One serious consequence of this is the nearly complete disappearance of the old noblesse oblige attitude of the old elite to non-elite and the commonality between them as parts of one nation. The new elite sees no difference between British workers and immigrants, whether legal or illegal, and prefers those who provide cheaper labor. The new elite is also multicultural and is educated in contempt of the British and overall Western culture and history. The non-elite is still mainly British, and its values are still based on the British nation-state and culture. This creates the dynamics of revolution vs. counter-revolution, and the author expects the ongoing fight to continue for a while.

MY TAKE ON IT:

I think that the diagnosis of the situation is, in general, correct and that it relates not only to Britain but to the whole Western world. Humanity is currently in the process of moving from being divided into separate nation-states and cultures competing between themselves into one unified global entity with one dominant culture all over the world. The question is what kind of culture and economic system will become dominant. The competitors are:

- The Western Enlightenment tradition, with its individualistic ideology and freedom, capitalist economy, and limited government divided into separate powers. The limited hierarchical control and distribution of resources provide individuals at the bottom with the opportunity to pursue their objectives the way they see fit.

- The pre-Enlightenment tradition, with its collectivistic ideology, hierarchical control from the top down, and complete subordination of individuals at the bottom to the will of individuals at the top.

Right now, the struggle between these competitors has taken the form of elite vs. non-elite at the national level, but often over global issues such as climate alarmism, top-down behavioral control, resource allocation, and similar issues. However, it is bound to consolidate into the worldwide struggle of elite vs. non-elite that will last for a while.

20240630-Indigenous Continent

MAIN IDEA:

This is probably the best book about the history of America, not as the history of the United States but the history of the northern part of the continent in which the English-speaking tribe of newcomers from Europe gradually, over the period of centuries, became the dominant tribe of the continent after fighting other European French and Spanish speaking tribes, all of them being allied with various local Indian tribes up until the near end of the struggle. Here is the author’s definition of the main idea of this book:” It offers a new account of American history by challenging the notion that colonial expansion was inevitable and that colonialism defined the continent, as well as the experiences of those living on it. Stepping outside of such outdated assumptions, this book reveals a world that remained overwhelmingly Indigenous well into the nineteenth century. It argues that rather than a “colonial America,” we should speak of an Indigenous America that was only slowly and unevenly becoming colonial. By 1776, various European colonial powers together claimed nearly all of the continent for themselves, but Indigenous peoples and powers controlled it. The maps in modern textbooks that paint much of early North America with neat, color-coded blocks confuse outlandish imperial claims for actual holdings. The history of the overwhelming and persisting Indigenous power recounted here remains largely unknown, and it is the biggest blind spot in common understandings of the American past.”

MY TAKE ON IT:

I think this book goes a long way in disassembling many ideological myths about the history of America. Either old myths, based on the ideology of white racial and cultural superiority, or new myths, based on the ideology of white racial and cultural inferiority, distort and diminish the real history of America. In reality, it would be meaningless to seek signs of superiority or inferiority between peoples and civilizations that were developing differently. Qualitatively, Euro-African and American civilizations were approximately equal, about 60 to 80 million people each before encounter. However, land available for human sustenance in America was multiple of that in Europe. Therefore, forces pushing the switch from a hunter-gatherer and/or low-intensity agriculture way of life were much weaker in America, leaving people with much more humane conditions of life with a lot less need for military-technological development for survival. It is not surprising that by all accounts, Europeans who were captured and adopted into a more humane Indian culture preferred to remain in this culture even if they had the opportunity to go back to European civilization. It is also unsurprising that European civilizations of much more intensive agriculture and dependence on military competition had better military technology. Consequently, initially, representatives of European civilizations in America were happily embraced by local tribes as valuable allies despite their negligible numbers. The question of who was dominant in these alliances probably would be answered differently in different cases. Still, up until the latest part of the period from 1492 to 1880s, it was mainly cases of some newcomers and locals fighting other newcomers and locals rather than newcomers fighting locals. It would be nice if the understanding of real history led to the embrace of common humanity and the elimination of all racist ideologies. Still, since as many people are making as good a living now from promoting anti-white racism as other people used to make from promoting anti-black and anti-indian racism in the past, it will take a while before these junk ideologies are fully left behind.

20240616-Blunder

MAIN IDEA:

This book reviews all kinds of reasons, mainly psychological, that caused people to make blunders. Here is the author’s description of its main idea:” Blunder is a book about judgment calls. It is the story of how smart people like Edison get caught in cognition traps and wind up defeating themselves. Most complex problems have complex causes, and no single factor can explain it all. This book offers one possible explanation for why people blunder. I suggest that we all sometimes fall into “cognition traps”—rigid ways of approaching and solving problems.4 Cognition traps are inflexible mind-sets formed from faulty reasoning. They are the stolid ways in which people approach and solve problems based on preconceived notions and preset patterns of thought.

The author also defines three different types of problems that cause people to make poor decisions and implement actions that lead to failure: mistakes, blunders, and cognition traps: ” A mistake is simply an error arising from incorrect data, like believing that an electric wire is running direct current when it’s actually on AC. A blunder, in contrast, is a solution to a problem that makes matters worse than before you began, like attempting to discredit a potentially liberating technology rather than adapting to it. Finally, a cognition trap is the mental framework that led you to a blunder, like the one I call static cling, the refusal to accept that a fundamental change is under way.” The book allocates one chapter to each of the 9 most typical problems that cause blunders.

MY TAKE ON IT:

This is quite an interesting collection of cases in which human psychology caused behavior problems that resulted in negative and sometimes deadly consequences. The book is big on factoids but relatively low on proposed solutions. I am actually more interested in solutions. To a significant extent, I think these problems are caused by the lack of education. I do not mean formal education, which is often nothing more than a combination of indoctrination with low levels of technical skills, such as reading, writing, and doing some formalized algorithmic tasks. It would be much better to expand education to game-playing that emulates real-life situations and provides timely and effective feedback on individual actions, pretty much like it is done naturally by children when they are not disturbed. It is probably coming with massive implementation of AI tools and a shift to decision-making to AI models trained on the many situations relevant to skills and behavior patterns needed to avoid blunders.

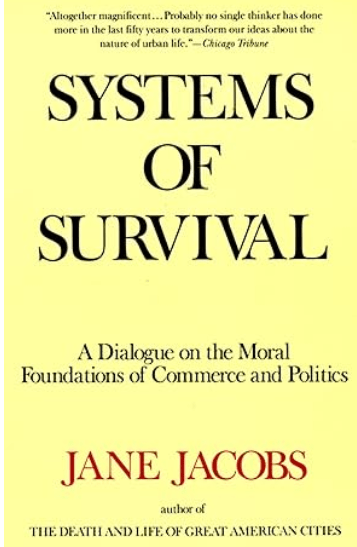

20240224 – Systems of Survival

MAIN IDEA:

Here is the author’s definition of the main idea of this book:” This book explores the morals and values that underpin viable working life. Like the other animals, we find and pick up what we can use, and appropriate territories. But unlike the other animals, we also trade and produce for trade. Because we possess these two radically different ways of dealing with our needs, we also have two radically different systems of morals and values—both systems valid and necessary.” From here follows the definition of two syndromes: Commercial and Guardian. Then, the book explores various aspects of these two syndromes, including their morals and corresponding types of human behavior depending on the preponderance of one or another syndrome in the worldview of individuals. Here are the key points:

MY TAKE ON IT:

For me, it is extremely interesting that the author of this book came to the same conclusions that I did, only from a completely different point of view. I look at it from the point of view of goods and services production and distribution when processes are based either on the voluntary cooperation of individuals in possession of resources or on a violent hierarchy forcing individuals to cooperate whether they want it or not.

The author of this book looks at the same dichotomy from a moralistic point of view, going into the details about human behavior relevant to each Moral syndrome, which is a proper approach for the moral philosopher.

My approach is to look at what kind of a system could be implemented to obtain the best of both sides of this dichotomy, which is a proper approach for the systems engineer that I am. So, my conclusion is that such a system should be based on minimizing the use of violence (governmental hierarchy) and maximizing the use of voluntary actions of free individuals (ownership of self and resources).

By the way, I expressed my views in a small essay, and here is the link:

20240217 – Conflict

MAIN IDEA: