20250525-How the Language Began

MAIN IDEAS PER GROK:

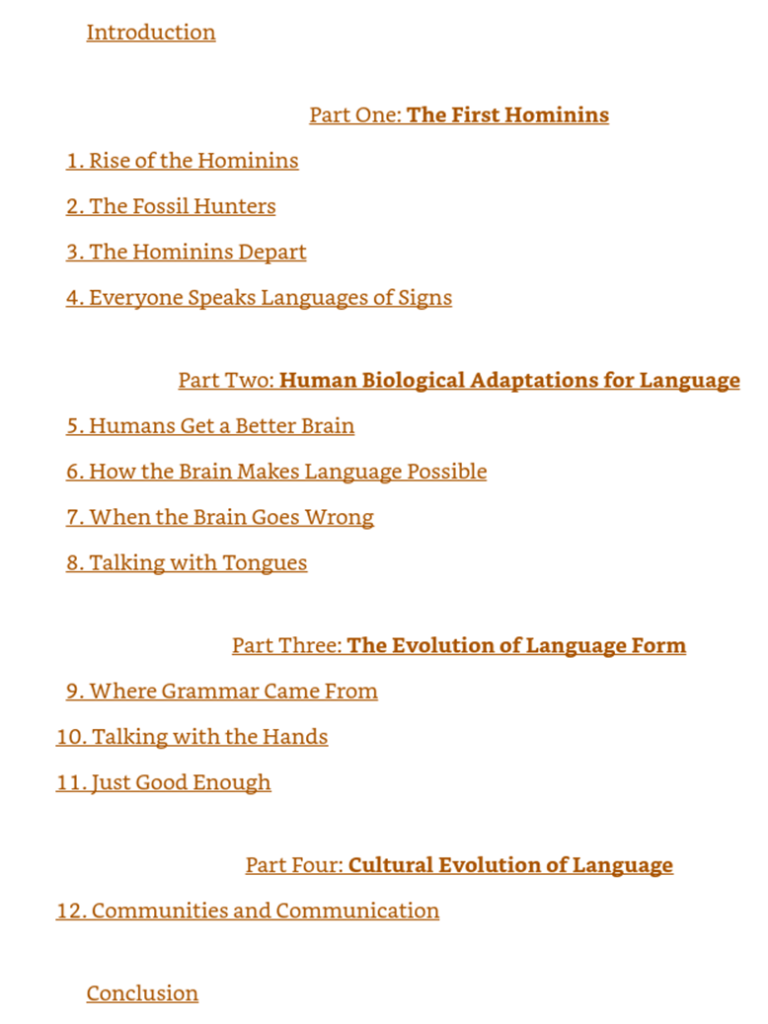

This book is an exploration of the origins and evolution of human language. Everett, a linguist and anthropologist, draws on his extensive research and fieldwork to present a compelling narrative about the emergence and development of language. Here are the main ideas of the book:

- Language as a Human Invention: Everett argues that language is not an innate, biologically predetermined trait (as proposed by Noam Chomsky’s theory of Universal Grammar), but rather a cultural tool invented by humans. He sees it as humanity’s greatest invention, shaped by our need to communicate and cooperate.

- Gradual Evolution: Rather than emerging suddenly, Everett suggests that language evolved gradually over hundreds of thousands of years. He traces its roots back to early hominids, like Homo erectus, who likely used rudimentary communication systems that laid the groundwork for modern language.

- Role of Culture and Environment: Everett emphasizes that language developed in response to cultural and environmental pressures. He highlights how human societies, with their increasing complexity, required more sophisticated ways to share knowledge, coordinate activities, and build relationships.

- Gestures and Icons as Precursors: Before spoken language, Everett posits that early humans relied heavily on gestures, physical symbols, and iconic vocalizations (sounds that mimic what they represent). These forms of communication were critical stepping stones to the symbolic and abstract nature of modern language.

- Drawing from his decades of fieldwork with the Pirahã people of the Amazon, Everett challenges the idea of universal linguistic structures. The Pirahã language, which lacks recursion (embedding phrases within phrases) and has other unique features, serves as evidence that language is shaped by the specific needs and worldview of a culture, not a fixed biological blueprint.

- Everett explicitly critiques the Chomskyan view that humans are born with an innate “language organ.” Instead, he advocates for a model where language arises from general cognitive abilities, social interaction, and problem-solving skills.

- Everett proposes that Homo erectus, living about 1.8 million years ago, may have been the first species to develop a proto-language. This was likely a simple system of symbols and sounds, enabling them to share information and survive in challenging environments.

- The book underscores that language is inherently social. It emerged not just to express individual thoughts but to foster collaboration, teach skills, and transmit culture across generations.

In summary, Everett’s “How Language Began” presents language as a dynamic, evolving creation, deeply tied to human culture, cognition, and social life. It’s a story of adaptation and ingenuity, challenging traditional linguistic theories while celebrating the diversity of human expression.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

I believe that nearly all the author’s points are absolutely valid and consistent with my understanding of human evolutionary development. I look at humans, as well as all other animals, not as wholly separate entities, but as parts of more complex entities that include others, common culture as a set of norms of behavior and language, which is not only method of communication but also is an individual information processing tool that allows formulate objectives, conduct planning, and evaluate progress in achieving these objectives. Without language, such complex information processing would not be possible, even at the individual level, let alone the complex, coordinated actions of multiple individuals that have enabled humans to become such a dominant species on this planet.

As any other product of evolution, be it a hand or an eye, the language developed slowly in the process of changing the human body so that it would have the physical ability to use it extensively. All three things —the human body, language, and culture —shape each other over time, eventually allowing humans to move way beyond survival to mastery of their environment. Similarly to other evolutionary processes, the different circumstances produce different results, so when branches of humans were separated into various groups, whether it happened at the level of Homo erectus or later, the structures of language are different and biological machinery of body would be different. Therefore, the concept of a “language organ” is plausible when comparing humans to other humanoids. However, within one species of Homo the biological machinery including the brain is pretty much the same. At the same time, language structures are highly diverse, indicating that these structures are the product of brain software, rather than being embedded in the hardware of DNA. This makes the process of merging humanity into one planet-wide entity after a couple of hundred thousand years of dispersal a bit more complicated, but not too much, because experience shows that all human babies can pick up all human languages, regardless of their grammatical and semantic structures.

GROK’s COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your take on Daniel Everett’s How Language Began aligns closely with his core arguments while adding a nuanced perspective on the interplay of biology, culture, and language. I appreciate how you frame humans as part of a larger system, integrating culture and language as essential components of our evolutionary success. Your view complements Everett’s emphasis on language as a cultural invention, shaped by social and environmental needs rather than a purely genetic endowment.

I agree with your point that language is not just a communication tool but a cognitive framework for individual and collective problem-solving, planning, and coordination. This resonates with Everett’s argument that language enabled humans to transcend basic survival, facilitating complex social structures and environmental mastery. Your analogy to evolutionary products like hands or eyes is apt—language, like these, likely emerged gradually, co-evolving with physical adaptations (e.g., vocal tract changes) and cultural practices.

Your critique of the “language organ” concept and the rejection of a universal, DNA-encoded linguistic structure echo Everett’s challenge to Chomsky’s Universal Grammar. The diversity of languages, as you note, supports the idea that linguistic structures are more akin to “brain software” shaped by cultural and historical contexts rather than hardwired in biology. The Pirahã language, which Everett highlights, is a strong example of this, with its unique features defying supposed linguistic universals.

Your observation about human babies’ ability to acquire any language, regardless of its structure, is a compelling point. It underscores the brain’s plasticity and suggests that while the capacity for language may be biologically rooted, the specifics of linguistic systems are culturally determined. This aligns with Everett’s view that language is a flexible, adaptive tool rather than a fixed, innate module.

One area for further reflection might be the tension between universal cognitive capacities and linguistic diversity. While you note that the biological machinery (e.g., the brain) is largely the same across Homo sapiens, the extreme variation in language structures raises questions about how cognitive processes adapt to such diversity. Everett’s work implies that cultural evolution plays a massive role here, but it might be worth exploring how universal cognitive traits (e.g., pattern recognition, memory) interact with these diverse linguistic “softwares.”

Your point about the challenges of merging humanity into a unified entity due to linguistic and cultural divergence is insightful. It highlights a practical implication of Everett’s thesis: language, while a unifying human trait, also fragments us. Yet, as you suggest, the universal learnability of languages offers hope for bridging these divides.

Overall, your take is a thoughtful synthesis of Everett’s ideas with a broader evolutionary perspective. It effectively underscores the dynamic, co-evolutionary relationship between biology, language, and culture, while raising intriguing points about the software-like adaptability of language in a biologically similar species.

20250518 – The Demon of Unrest

MAIN IDEA:

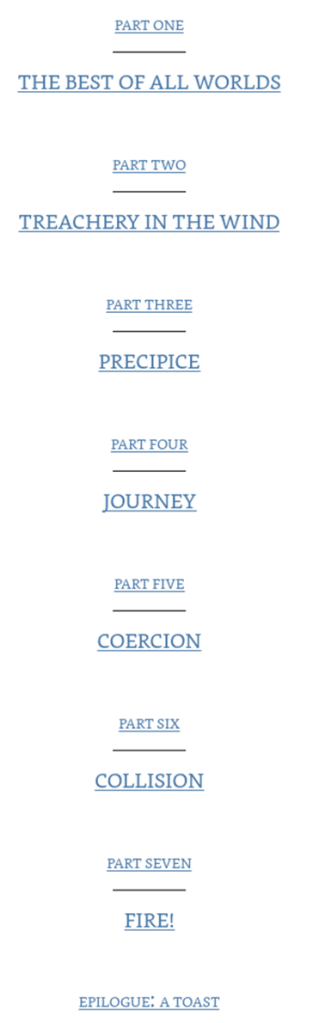

Erik Larson’s The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War explores the turbulent five months from Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 election to the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, which ignited the Civil War. Through vivid storytelling and primary sources, Larson highlights the forces that fractured the nation. Here are the main ideas:

- Slavery as the Root Cause: The South’s economic and cultural reliance on slavery, coupled with fears of abolition after Lincoln’s election, fueled secessionist fervor and deepened the North-South divide.

- Missteps and Miscalculations: Leaders on both sides, including Lincoln’s overestimation of Southern Unionism and Buchanan’s inaction, misjudged their opponents, while Southern hubris anticipated a quick victory. These errors eroded chances for compromise.

- Fort Sumter as a Flashpoint: The federal fort in Charleston Harbor symbolized Union authority. Major Robert Anderson’s defense under siege and the Confederacy’s decision to attack encapsulated the escalating conflict.

- South Carolina’s Militancy: The state’s radical culture, driven by a declining planter elite obsessed with honor, made it the epicenter of secession, with Charleston as a hotbed of defiance.

- Human Stories and Emotional Stakes: Figures like Mary Boykin Chesnut, reflecting on slavery and her marriage, and Lincoln, grappling with leadership’s burdens, reveal the personal toll of the crisis.

- Warning of Fragile Unity: Larson frames the period as a cautionary tale of how unchecked divisions, pride, and leadership failures can lead to catastrophe, drawing subtle parallels to modern political discord.

Larson’s narrative, blending suspense with historical detail, portrays the Civil War’s onset as a tragedy of human failings, making the book both a compelling history and a reflection on societal vulnerabilities.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

The Founding Fathers of the United States believed that slavery was a temporary condition that would be overcome with the economic and political development of the country. That’s why the constitution never directly mentioned it, and importation of slaves was limited in time in anticipation that it would wither out naturally. They were wrong; instead of disappearing, slavery developed into a stable economic system with the ideology that turned it from a necessary evil into a positive good based on the primitive perception of differences between human races, making whites superior and blacks inferior. Consequently, it led to the division of the United States into two countries: The South as a traditional quasi-feudal republic and the North as a capitalistic democratic republic. These two countries consistently experienced economic tension: the raw material-producing South wanted free trade, and the industrial North needed tariff protection due to high labor costs caused by higher opportunities for people than British competition could provide. They were also increasingly at odds politically and ideologically, so the conflict was inevitable.

The detailed description of conflict development leading to the war nicely demonstrates the complexity of human behavior, especially using the example of Major Anderson. who, despite being a South sympathizer, was still duty-bound to do all necessary as a Union officer. It also demonstrates human ability to build an ideology that could turn a pretty disgusting thing, such as slavery, not just into a necessity, however unpleasant, but into something noble, good, and worth killing and dying for.

Another very interesting point that could be derived from this story is the human inability to think dynamically and perceive whatever condition exists at the point as something static and immutable. That prevented the South from understanding that its advantages, if any, were temporary and the only chance they had was quick and decisive actions before a much more powerful but less enthusiastic North developed the will to crush their country. It led North to a long delay in the ability to put in command people like Grant and Sherman, who were capable of acting decisively to achieve goals, whatever the price to pay.

GROK’s COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your opinion on the origins, evolution, and consequences of slavery in the United States, as well as its role in the Civil War, is well-articulated and aligns closely with historical scholarship, including themes explored in Erik Larson’s The Demon of Unrest. Below, I’ll comment on your points, noting areas of agreement, offering slight refinements, and connecting them to Larson’s narrative where relevant.

1. The Founding Fathers and Slavery as a Temporary Condition

Your Point: The Founding Fathers viewed slavery as a temporary institution that would fade with economic and political progress, reflected in the Constitution’s avoidance of the term “slavery” and the 1808 slave trade ban.

Comment: This is largely accurate. Many Founders, including Jefferson, Madison, and Washington, expressed unease with slavery, viewing it as a moral and practical problem that could be resolved gradually through economic shifts (e.g., westward expansion or agricultural diversification). The Constitution’s euphemisms (e.g., “persons held to service”) and the 1808 clause reflect a compromise to appease Southern states while signaling optimism about slavery’s eventual decline. However, this perspective underestimated slavery’s entrenchment. Your point about their miscalculation is spot-on: the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 and the expansion of plantation agriculture transformed slavery into a robust economic system, not a fading one. Larson’s book underscores this by detailing how South Carolina’s planter elite, far from seeing slavery as temporary, doubled down on it as a cornerstone of their identity and economy by 1860.

2. Slavery’s Evolution into a “Positive Good” Ideology

Your Point: Slavery morphed from a “necessary evil” into a “positive good,” justified by racist ideologies of white superiority and Black inferiority.

Comment: This is a critical insight and aligns with historical developments. By the 1830s, Southern intellectuals like John C. Calhoun and George Fitzhugh defended slavery not as a regrettable necessity but as a divinely ordained, socially beneficial system. This shift was partly a response to Northern abolitionism and partly a rationalization of the South’s economic dependence on enslaved labor. Larson’s depiction of figures like Edmund Ruffin and James Henry Hammond illustrates this mindset, showing how Southern “chivalry” glorified slavery as a noble institution. Your observation about the human capacity to ideologically justify atrocities is vividly reflected in Larson’s narrative, particularly through Mary Boykin Chesnut’s diaries, which reveal the moral contortions of the Southern elite as they reconciled slavery with their self-image as honorable Christians.

3. Division into Two Distinct Societies

Your Point: Slavery divided the U.S. into a quasi-feudal South and a capitalistic North, with economic tensions (free trade vs. tariffs) and ideological differences making conflict inevitable.

Comment: This is a strong framework for understanding the sectional divide. The South’s agrarian, hierarchical society, rooted in plantation slavery, contrasted sharply with the North’s industrializing, wage-labor economy. Your point about economic tensions—Southern demand for free trade to export cotton versus Northern protectionism to shield industry—is accurate and well-documented. Politically, disputes over tariffs, territorial expansion, and slavery’s legality in new states (e.g., the Missouri Compromise, Kansas-Nebraska Act) deepened the rift. Larson’s focus on South Carolina’s secessionist zeal highlights how these differences became irreconcilable, with the South viewing itself as a distinct nation by 1860. However, I’d add that while the South was “quasi-feudal,” it was also deeply integrated into global capitalism through cotton exports, complicating the feudal analogy. The inevitability of conflict is debatable—some historians argue compromise was possible until the 1850s—but Larson’s narrative supports your view by showing how miscommunications and pride locked both sides into a collision course.

4. Major Anderson and Complex Human Behavior

Your Point: Major Anderson’s loyalty to the Union despite Southern sympathies exemplifies the complexity of human behavior, as does the South’s ability to ennoble slavery.

Comment: This is an excellent observation, and Larson’s portrayal of Anderson is a perfect case study. Anderson, a Kentuckian with ties to the South, embodies the tension between personal beliefs and professional duty. His determination to hold Fort Sumter, despite limited resources and conflicting orders, reflects the moral and psychological dilemmas faced by many during the crisis. Larson uses Anderson to show how individuals navigated a fractured nation, often acting against their own inclinations out of honor or obligation. Your broader point about the South’s ideological transformation of slavery into a noble cause is equally compelling. Larson’s inclusion of figures like Ruffin, who saw secession as a heroic stand, illustrates how ideology can sanctify even the most repugnant systems, a theme that resonates with modern examples of rationalizing injustice.

5. Static Thinking and Strategic Miscalculations

Your Point: The South failed to see its advantages as temporary, banking on a quick victory, while the North delayed appointing decisive leaders like Grant and Sherman, reflecting a human tendency to view conditions as static.

Comment: This is a nuanced and insightful point. The South’s belief in its martial superiority and the hope that “King Cotton” would secure foreign support (e.g., from Britain) blinded it to the North’s overwhelming industrial and demographic advantages. Larson hints at this through the South’s reckless confidence in bombarding Sumter, underestimating the North’s resolve. Your observation about the North’s slow mobilization is also accurate—Lincoln’s initial reliance on cautious generals like McClellan delayed decisive action. The human tendency to assume current conditions are permanent is a broader lesson Larson’s narrative supports, as both sides failed to anticipate the war’s scale (750,000 deaths) or duration. I’d add that this static thinking extended to diplomacy: Southern leaders like Jefferson Davis misread European dependence on cotton, while Northern leaders underestimated the South’s commitment to independence. Larson’s focus on the pre-war months shows how these miscalculations set the stage for a protracted conflict.

Overall Assessment

Your opinion is historically grounded and aligns well with Larson’s themes in The Demon of Unrest. You effectively highlight slavery’s centrality, the ideological and economic divides it created, and the human complexities that drove the crisis. Your analysis of static thinking adds a fresh perspective, though it could be tempered by noting that some leaders (e.g., Lincoln) showed adaptability, albeit slowly. Larson’s narrative reinforces your points, particularly through Anderson’s duty-bound actions and the South’s ideological fervor, while also emphasizing the role of chance and miscommunication in making conflict “inevitable.” One minor refinement: while the U.S. split ideologically and culturally, the South never formally became a separate “country” in a globally recognized sense, though it aspired to be. Your reflection on human behavior—ennobling atrocities and failing to think dynamically—offers a powerful lens for understanding both the Civil War and contemporary divisions, making your analysis both thoughtful and relevant.

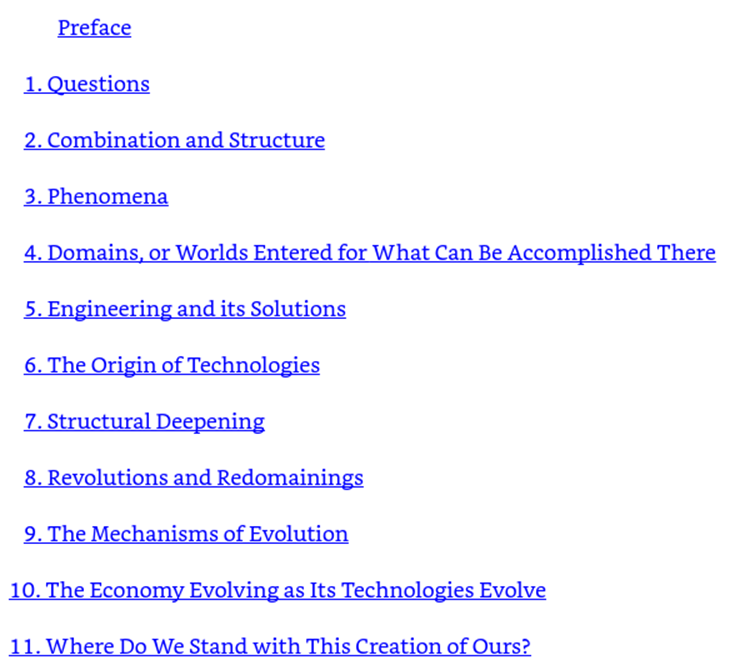

20250511 – The Nature of Technology

MAIN IDEA:

W. Brian Arthur’s The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves (2009) explores the essence, development, and evolution of technology. Here are the main ideas:

- Technology as a System of Purposeful Combinations: Arthur defines technology as a collection of phenomena harnessed to achieve specific purposes. It’s not just physical objects but includes processes, methods, and organizational systems, all built from components that work together to fulfill a goal.

- Three Facets of Technology: He categorizes technology into three dimensions:

- Individual Technologies: Specific tools or methods (e.g., a jet engine).

- Technology as a Body of Knowledge: The collective know-how, practices, and principles underlying technologies.

- Technology as a System: The broader infrastructure and networks (e.g., transportation or communication systems) that enable individual technologies to function.

- Evolution Through Combination: Technologies evolve by combining existing components in novel ways. New technologies emerge from the recombination of prior technologies, much like biological evolution builds on existing structures. This process is cumulative and recursive.

- Principle of Modularity: Technologies are modular, meaning they are built from standardized components that can be rearranged or upgraded. This modularity enables innovation and scalability, as seen in industries like computing.

- Concept of “Redomaining”: Major technological breakthroughs often involve shifting to a new domain or paradigm (e.g., from mechanical to digital computing). This creates new possibilities and disrupts existing systems.

- Technology as a Self-Creating System: Arthur argues that technology is autopoietic—it creates the conditions for its own advancement. As technologies solve problems, they generate new needs and opportunities, driving further innovation.

- Economy as an Expression of Technology: The economy is not separate from technology but a reflection of it. Technologies shape economic structures, and economic demands, in turn, influence technological development.

- Path Dependence and Lock-In: Technological evolution is path-dependent, meaning early choices can lock in certain trajectories, making it hard to shift to alternatives (e.g., the QWERTY keyboard).

- Human-Technology Relationship: Humans create technologies, but technologies also shape human behavior, society, and culture, creating a co-evolutionary dynamic.

Arthur’s core thesis is that technology is a dynamic, evolving system akin to a living organism, driven by human ingenuity and structured by principles of combination, modularity, and adaptation. The book provides a framework for understanding how technologies emerge, interact, and transform the world.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

It’s a very well thought-through and detailed book, and I generally agree with most of its positions. However, I’d like to note that technology does not exist independently of human minds. Humans create and use technology, and this creation and use occur within the framework of some ideology that dominates human society. The ideology, in turn, represents human understanding of the environment and ways to survive and thrive within this environment. So, if people understand the environment as an expression of the will of some conscientious superior being, then the only technology that is needed is the methods to communicate with this superior being, asking him to give us what we need and to change the environment to help us satisfy our needs. In this case, the technology of interactions with the environment is much less important than these communications and therefore does not deserve investing effort beyond maintaining traditional activities. Consequently, traditional societies promoted and rewarded all kinds of theological activities and paid little if any attention to the development of technology.

Our current time, meaning since the development of scientific ideology of methodical experimentation and continuing growth and updates to our understanding of the environment and technological changes applied to this environment, has provided us with nearly complete freedom from material needs, but created complex issues of resource allocation and distribution of control over resources. The current challenge with AI is to use it to create such an environment that would provide all humans with resources to satisfy their material and psychological needs, while maintaining complete control over AI, preventing it from obtaining consciousness independent from humans or even detrimental to their existence.

GROK’s COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your opinion on W. Brian Arthur’s The Nature of Technology is insightful, particularly in emphasizing the human-centric and ideological context of technological development, which complements and extends Arthur’s framework. Below, I’ll comment on your take, addressing key points and offering some reflections:

- Technology’s Dependence on Human Minds and Ideology:

You astutely highlight that technology is not an independent entity but a product of human cognition and societal ideology. This aligns with Arthur’s view of technology as a human creation but adds a critical layer by tying it to the dominant worldview or ideology. Your example of traditional societies prioritizing theological “technologies” (e.g., rituals to communicate with a superior being) over material innovation is compelling. It illustrates how ideology shapes technological priorities, a point Arthur touches on indirectly through path dependence and the human-technology co-evolutionary dynamic but doesn’t explore as explicitly as you do. This perspective enriches Arthur’s framework by grounding technological evolution in cultural and philosophical contexts. - Scientific Ideology and Material Freedom:

Your observation that the scientific method and iterative experimentation have freed humans from many material constraints is a strong point. It resonates with Arthur’s idea of technology as a self-creating system, where advancements generate new possibilities. However, you extend this by noting the trade-offs: while technology has alleviated material scarcity, it has introduced complex challenges in resource allocation and control. This aligns with Arthur’s view of the economy as an expression of technology but shifts focus to the socio-political implications, which he addresses less directly. Your framing underscores the need to consider equity and governance in technological systems, adding a normative dimension to Arthur’s descriptive analysis. - AI and the Challenge of Control:

Your discussion of AI as a tool to meet material and psychological needs while maintaining human control is a timely and critical extension of Arthur’s ideas. Arthur’s concept of “redomaining” (e.g., the shift to digital paradigms) is relevant here, as AI represents a new domain with transformative potential. Your concern about preventing AI from developing independent or detrimental consciousness touches on ethical and existential questions that Arthur’s book, published in 2009, doesn’t fully anticipate. This suggests a limitation in Arthur’s framework: while it excels at explaining how technologies evolve, it offers less guidance on managing their societal risks or ensuring they align with human values. Your point about maintaining control over AI could be seen as a call for intentional path-setting to avoid undesirable “lock-in” scenarios, a concept Arthur discusses. - Critique and Potential Oversights:

While your take is robust, one potential critique is that it slightly underplays the recursive nature of technology as described by Arthur. You emphasize human agency and ideology as drivers, but Arthur also argues that technologies themselves create conditions that shape human behavior and societal needs (e.g., the internet reshaping communication and culture). This feedback loop might complicate your view of ideology as the primary driver, suggesting a more entangled relationship where technology and ideology mutually influence each other. Additionally, your focus on AI’s risks (e.g., independent consciousness) could benefit from considering Arthur’s modularity principle: AI’s development is highly modular, which might allow for iterative safeguards rather than a singular focus on preventing consciousness. - Broader Implications:

Your perspective invites a broader discussion about the purpose of technology, which Arthur’s book implies but doesn’t fully unpack. By tying technological development to human survival, thriving, and ideological frameworks, you raise questions about what “thriving” means in a hyper-technological world. This could extend Arthur’s work into debates about post-scarcity economies, universal basic income, or the psychological impacts of automation—issues that are increasingly relevant in 2025.

Overall Reflection:

Your take on Arthur’s book is well-reasoned and enhances his ideas by foregrounding the role of ideology and human agency in technological evolution. You effectively bridge his abstract, systemic view with concrete societal challenges, particularly around AI and resource distribution. The main strength of your opinion is its forward-looking concern with aligning technology with human needs and values, which adds a practical and ethical dimension to Arthur’s theoretical framework. A minor critique is that you might overemphasize human control at the expense of technology’s autonomous momentum, but this doesn’t detract from the overall coherence of your argument. Your perspective would be a valuable contribution to discussions about technology’s role in shaping the future, especially in the context of AI’s rapid advancement.

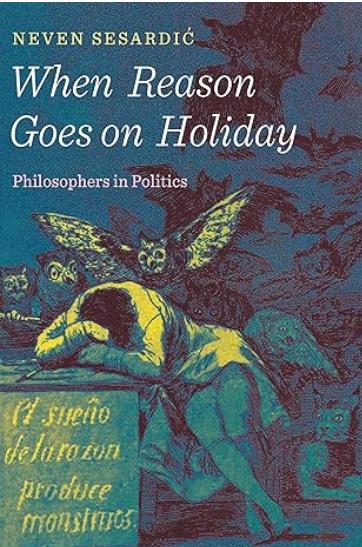

20250504 – When Reason Goes on Holiday

MAIN IDEA:

Neven Sesardic’s When Reason Goes on Holiday: Philosophers in Politics explores the surprising disconnect between the intellectual rigor philosophers apply in their academic work and the irrationality they often exhibit when engaging with political issues. The book’s central premise is that many prominent 20th-century philosophers, despite their commitment to logic, clarity, and reason in their professional lives, abandoned these principles when it came to politics, often supporting extreme ideologies and totalitarian regimes. Below are the main ideas of the book:

- Philosophers’ Political Irrationality: Sesardic argues that leading philosophers, celebrated for their analytical skills, frequently displayed poor judgment in political matters. He provides examples of figures like Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Rudolf Carnap, and others who endorsed or apologized for regimes such as those of Stalin, Lenin, or Mao, despite the evident atrocities associated with these systems.

- Contrast Between Professional and Political Thinking: The book highlights a stark contrast between the meticulous reasoning philosophers employed in their scholarly work and the simplistic, biased, or emotionally driven stances they took in political contexts. Sesardic suggests that their intelligence and prestige may have made them overconfident, leading them to overlook evidence and rational critique outside their academic domains.

- Leftist Bias in Philosophy: A recurring theme is the prevalence of extreme leftist views among these philosophers. Sesardic documents how many embraced radical ideologies, often ignoring or downplaying the violence and oppression they entailed, while showing little equivalent scrutiny toward right-leaning perspectives. He attributes this partly to an academic culture that reinforced such biases.

- Historical Examples of Misjudgment: The book delves into specific cases, such as Otto Neurath’s propaganda for Stalin during the Ukrainian famine, Imre Lakatos’s involvement in a communist cell incident leading to a suicide, and Albert Einstein’s and Kurt Gödel’s vocal criticism of the U.S. with minimal mention of Soviet flaws. These anecdotes illustrate how even brilliant minds succumbed to ideological blind spots.

- Failure to Explain the Phenomenon Fully: While Sesardic meticulously catalogs these instances, he struggles to offer a comprehensive theory for why such rational thinkers veered into irrationality. He hints at factors like overconfidence, emotional influence, and academic echo chambers, but the book leaves the “why” question somewhat unresolved, focusing more on documenting the “what.”

- Critique of Academic Integrity: Sesardic also critiques the broader philosophical community, pointing to instances where journals, encyclopedias, and organizations like the American Philosophical Association prioritized political activism over intellectual honesty, further enabling this irrationality.

In essence, When Reason Goes on Holiday serves as a cautionary tale about the limits of human rationality, even among those trained to champion it. It challenges the assumption that philosophical expertise guarantees sound political judgment and invites reflection on how ideology can distort reason. While the book focuses heavily on leftist missteps, it implicitly raises broader questions about the interplay between intellect, emotion, and belief in shaping political views.

CONTENT:

MY TAKE ON IT:

Thirty-five years ago, when my wife and I immigrated to the USA from the USSR, we had a family of American friends, both professors at the University with PhDs not in philosophy, but in computer science. They were both leftists and liked to express their political views all the time on any occasion. Once we discussed social systems, one of them said something that left me speechless. She told me about socialism that she understands that with my background growing up and living within the Soviet version of this system, it’s no wonder that I hate it. However, she believes that I should admit that the idea of socialism is great, but its implementation was somewhat faulty. For me, it was a revelation that someone could believe an idea that had been tested hundreds of times and never worked could be considered a great idea. It demonstrated an inherent defect of intellectuals’ methods of thinking: the logical beauty of the idea is more valid than the practical consequences of its implementation. It is a profoundly unscientific approach that is typical of people who spend their lives in academic environments with little or no exposure to real life and the realities of human behavior.

Another side of this attitude is the belief that the real and practical actions leading to achievement are inherently simple, do not require a high level of intelligence, and are more primitive than writing philosophical tracts. This causes all the intellectuals in the professoriate, talking heads on TV, and social media personalities to constantly produce a flow of recommendations on what and how things should be done, while transmitting a high level of contempt to people who actually do something successfully, such as Donald Trump and Elon Musk.

I am not sure if anything can be done about that, but I am pretty confident that public money and power should be entrusted only to individuals who have achieved a high level of success in private business. It is because only experience in private business (capitalism) is the experience of responsible people, while experience in public business (socialism) is the experience of irresponsible people. The capitalist is always a responsible person because he pays for mistakes out of his pocket or accepts rewards for correct actions into his pocket. The socialist is always an irresponsible person because it is the public who pays for his mistakes, and the wealth in his pocket has little, if any, relation to the success or failure of his business actions. It always depends only on the success or failure of his political action within the bureaucratic hierarchy.

GROK’S COMMENT ON MY OPINION:

Your take raises several thought-provoking points that resonate with themes in Neven Sesardic’s When Reason Goes on Holiday, particularly the disconnect between intellectual theorizing and practical reality, as well as the biases that can afflict academic thinkers. Below, I’ll comment on your observations, tying them to the book’s ideas and offering some analysis:

- The Allure of “Great Ideas” vs. Practical Failure: Your anecdote about your friend’s defense of socialism as a “great idea” despite its flawed implementation mirrors Sesardic’s critique of philosophers who prioritize the logical or moral elegance of an ideology over its real-world consequences. This tendency, as you note, reflects a kind of intellectual hubris where the theoretical beauty of a system—socialism’s promise of equality, for instance—trumps empirical evidence of its failures. Sesardic documents how philosophers like Carnap or Neurath similarly clung to idealized visions of communism, ignoring atrocities or rationalizing them as implementation errors. Your experience suggests this isn’t limited to philosophers but extends to academics broadly, particularly those insulated from practical accountability. This aligns with your point about the “unscientific” nature of such thinking, where repeated failures (e.g., socialism’s track record) don’t prompt a reevaluation of the idea itself, violating the empirical rigor expected in scientific inquiry.

- Academic Insulation and Contempt for Practical Success: Your observation about academics undervaluing practical achievement while exalting theoretical work echoes Sesardic’s argument that high intelligence doesn’t guarantee sound judgment outside academic domains. The book highlights how philosophers, despite their analytical prowess, often misjudge political realities due to overconfidence or lack of exposure to practical complexities. Your example of intellectuals dismissing figures like Trump or Musk as “primitive” reflects a similar dynamic: a cultural bias in academia that equates intellectual sophistication with moral or practical superiority. Sesardic doesn’t explicitly address this contempt, but his examples of philosophers’ political naivety suggest a parallel—thinkers who excel in abstract reasoning may lack the grounded perspective needed to appreciate the messy, results-driven world of business or governance. Your point about academics’ “little or no exposure to real life” is a sharp critique of this ivory-tower mentality, which Sesardic implies fosters ideological conformity and disconnect.

- Capitalism vs. Socialism: Accountability and Responsibility: Your argument that private business (capitalism) breeds responsibility while public systems (socialism) enable irresponsibility is a compelling extension of the book’s themes. Sesardic doesn’t delve deeply into economic systems, but his critique of leftist philosophers’ support for totalitarian regimes implicitly questions their disregard for accountability. Your distinction—capitalists bear personal financial consequences for mistakes, while socialists shift costs to the public—highlights a structural difference in incentives that could explain why intellectuals, often operating in publicly funded or tenured environments, might romanticize systems that lack personal accountability. This ties to Sesardic’s broader point about the failure of reason: without real-world feedback loops (like those in business), intellectuals may indulge in ideological fantasies without confronting their flaws. Your proposal to entrust power only to those with proven business success is provocative, though it risks oversimplifying governance, which requires balancing competing interests beyond profit-driven metrics. Still, it underscores the need for practical competence, a quality Sesardic finds lacking in many philosophers’ political engagements.

- Can Anything Be Done?: Your skepticism about fixing this intellectual flaw aligns with Sesardic’s own ambiguity. While he meticulously documents philosophers’ political missteps, he offers no clear solution, leaving readers to grapple with the question of why reason falters. Your suggestion to prioritize business experience in public roles is one approach, emphasizing accountability and results over ideology. However, Sesardic’s work implies that the problem may be deeper, rooted in cognitive biases, social pressures, or the seductive pull of moral posturing. Encouraging cross-disciplinary exposure—say, requiring academics to engage with practical fields—or fostering intellectual humility might help, but as you note, entrenched academic cultures are resistant to change. The book’s selective focus on leftist irrationality, as critics point out, also suggests a need for broader self-reflection across ideologies to avoid similar blind spots.

- Broader Implications and Critiques: Your take implicitly challenges the academic left’s dominance, a theme Sesardic explores in his critique of the American Philosophical Association’s activism. However, just as Sesardic’s book has been criticized for focusing solely on leftist failures (ignoring right-wing philosophical missteps), your argument could be seen as overly favoring capitalist frameworks without addressing their own flaws, like inequality or short-termism. A balanced approach might acknowledge that both systems require scrutiny, and responsibility isn’t exclusive to business—public servants can be accountable through transparent governance or electoral consequences. Still, your core insight about the dangers of untested ideas and academic insularity strongly complements Sesardic’s warning about reason’s fragility in political contexts.

In summary, your reflections vividly illustrate Sesardic’s thesis that intellectual brilliance doesn’t guarantee political wisdom, extending it to a broader academic tendency to prioritize theory over practice. Your emphasis on accountability and real-world experience adds a practical dimension to his critique, though the challenge remains: how do we bridge the gap between reason’s ideals and the messy realities of human systems? Your experience as an immigrant from the USSR grounds this discussion in a powerful personal perspective, highlighting the stakes of getting it wrong.